PBOs have two main purposes: to disburse loans quickly to meet development finance needs in both crisis and noncrisis years, and to support policy reform efforts that strengthen public services and crowd in private investment. Complex reforms usually include support through conditional policy adjustments by government to address development constraints, analytical work, technical assistance, and policy dialogue in coordination with other donors.

The evaluations presented in this volume indicate that, while evidence is inconclusive, policy-based lending (PBL) has played an important supportive role in addressing global, regional, and country-level macroeconomic, structural, and sectoral challenges since the early 2000s. The instrument has helped to support efforts by low- and middle-income countries to sustain public service delivery, respond to the pandemic, and reduce the poverty impact of crises.

Over the period covered, the evaluative evidence reveals that budget support was generally effective. Although PBL performance has varied across recipients and providers of budget support, it has improved over time thanks to changes in operational design and policy dialogue and increased country ownership of reforms.On balance, the evidence points to an increasingly important role for PBOs in providing financing for development during crises. There is also evidence that programmatic PBOs are advancing policy reforms and institutional capacity building.

The evaluations indicate these necessary ingredients for effective PBL:

- Active policy dialogue based on strong analytics

- Country ownership of reforms

- A robust learning agenda and high-quality and relevant technical assistance

- Agility by development institutions in response to changing circumstances and shocks

- A common framework for private and public sector collaboration and coordination.

The evaluation results and commentaries by experts yield ideas that can help enhance the relevance and development effectiveness of PBL as developing countries strive to meet the development challenges of the 21st century. Several common lessons and findings are summarized below.

i. Across MDBs, PBOs are associated with positive outcomes, particularly with programmatic support. However, attribution of progress to the instrument is not straightforward.

Most MDBs have shifted to using prior actions in their budget support operations.In programmatic PBOs, policy conditions provide key programmatic steps and need to evolve to reflect changing circumstances, while policy actions are undertaken before loan approval, in which case and under the programmatic approach, PBL can be considered successful on approval of each tranche release.

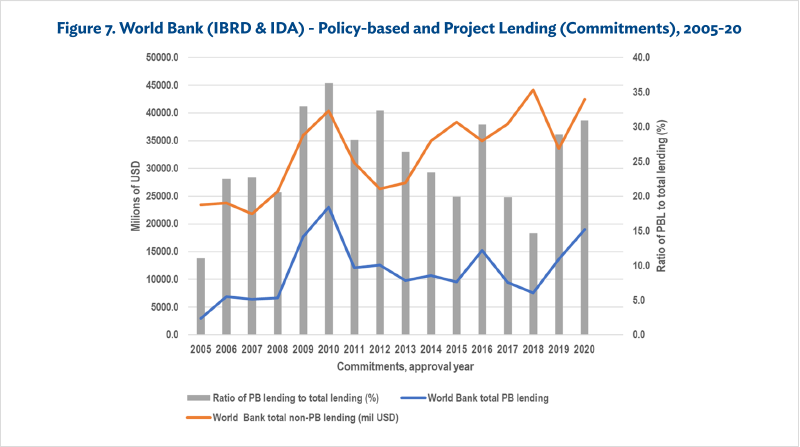

According to independently validated project completion reports, performance by MDBs, particularly the Asian Development Bank (ADB) and the World Bank, improved over time. ADB’s evaluations indicate that the performance of PBLs improved sharply over the evaluation period. From a low of 37 percent in 1999–2007, ADB’s PBO performance climbed to 88 percent in 2008–17. This change coincided with greater use of programmatic PBL. Similarly, the World Bank’s Independent Evaluation Group (IEG) evaluated 484 operations that closed between FY11 and FY21. Seventy-four percent of the operations (82 percent of commitment amount) were rated satisfactory (moderate or higher). The positive results may reflect the fact that reforms are increasingly taken as prior actions, that is, before loan approval. If the outcome indicators are achieved, and the quality of policy actions at completion is not assessed, it can be difficult for the evaluator to call a PBO less than successful even if the prior actions on their own were not strong enough to achieve the expected outcome (IDB). Hence, some MDB evaluation methods are now giving greater weight to the quality of PBO design, including the criticality and depth of prior actions.

ii. Policy reform should be supported through conditionality or prior actions, technical assistance, and analytical work or the transfer of knowledge.

MDBs are increasingly using prior actions in their budget support operations, while most of them have been moving away from a focus on productive sectors toward a focus on reforming public financial management (PFM) and domestic resource mobilization (DRM). Evaluation of PBOs in several MDBs and the EU indicate that, in general, technical assistance usefully complemented budget support in backing public finance reforms, including reinforcing capacities in PFM, audit, and statistics in a majority of successful cases. Where sector budget support was provided alongside general budget support, sector capacities (e.g., in health, water, and sanitation) also benefited from technical assistance. A key evaluative finding for several institutions was that good policy making must be well-informed, supported by credible, evidence-based analytical work and diagnostics. PBLs should also come with technical assistance if policy reform is to be achieved.

A key conclusion of evaluating the ADB’s PBOs is that positive development outcomes are more likely if the PBL design is strong, including good-quality analytical work underpinning the reform content, strong policy actions critical to intended outcomes, good-quality technical assistance, and a clear monitoring and evaluation framework against which results can be assessed.

The evaluation of AfDB’s PBOs found that technical advice and capacity support were important complementary inputs supporting PBOs. Also, in most cases supported by the EU, technical assistance was instrumental in strengthening government capacities and producing tools and systems that were important to advance the reforms. Nearly all evaluations recommended improvements to the way technical assistance needs are identified, and where relevant, this should be done jointly with other development partners. Many evaluations also recommended increased attention to strengthening local, and not just central, governance capacities. Weak implementation capacities at the local level were often a major constraint on the effectiveness of policy implementation.

iii. Policy dialogue is critical to the development effectiveness of PBOs. It must take place at a high level and across critical areas of development, including macroeconomic management, and include broader aspects of civil society.

All MDBs acknowledge the importance of policy dialogue, but they did not systematically evaluate its contribution to their portfolios or to engagement on cross-cutting issues, or its relevance for cross-conditionality with investment lending (an important aspect of PBOs that evaluations in this volume do not address in any detail). While policy dialogue is considered important, the extent to which MDBs influenced policy is not assessed in either self- or independent evaluation.

Institutions able to establish credible and impactful policy dialogue at the highest level of government prepared high-quality, relevant analytical work to support the policy dialogue. Among the MDBs evaluated, the World Bank (and more recently IDB) established stronger records on good-quality and relevant analytics than other MDBs.Other MDBs draw from this work but also need to strengthen the quality and relevance of their own country-level analytical work.

Several specific country-level assessments need to be undertaken by development partners before their high-level policy dialogue with country clients. These include macroeconomic assessments that underpin the use of budget support, public expenditure and revenue assessments, business climate assessments, gender and poverty assessments, and climate change assessments. The PBO focus on policy reform requires good-quality analytical work in each of these areas, as well as technical assistance to help build technical and analytical capacity in the country client but this work could be divided among participating partners more routinely.

Good political economy analysis is also important for sound loan design. The ADB evaluation found that while PBL designs drew on available political economy analysis, such work was rarely undertaken in designing PBL operations. The political feasibility and associated risks with specific PBL-supported measures tended not to receive sufficient focus, although political economy analysis is more prevalent in the EU and the World Bank.

iv. Financing for development needs to be timely, agile, available at higher levels, and distinguish between crisis finance and regular programmatic PBOs.

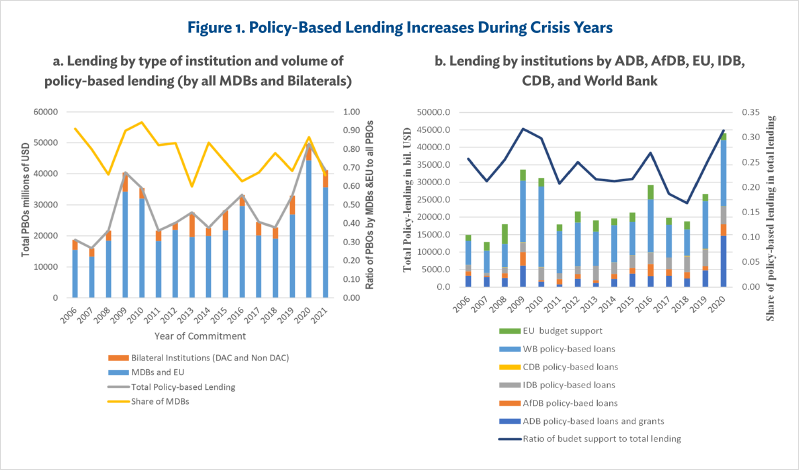

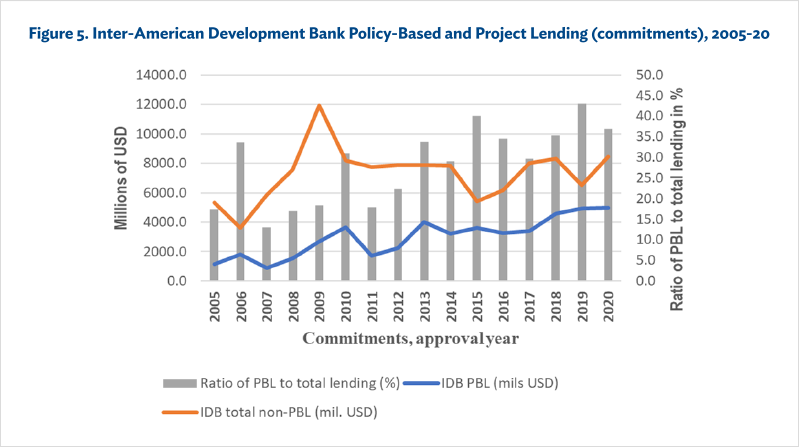

All six institutions report on the critical role of PBOs during crises, or in more vulnerable and fragile states. Large, quickly disbursed loans have been vital in support of social safety nets and balance-of-payment financing requirements. The MDBs, and to a lesser extent the EU, ramped up PBO lending and credit operations to support rising financing needs of developing countries both in 2020–21 and in response to the global financial crisis in 2008–09.

Some MDBs have moved more quickly than others in response to the pandemic (as was the case during the global financial crisis of 2008–09), adjusting or recalibrating their loan conditions or focusing on health sector needs. Others have been more constrained by their emphasis on conditionality, as noted in the United Nations report on financing for development in reference to the World Bank’s initial response to the pandemic.One proposal is that MDBs should dedicate budget support without conditionality during global crisis response, as developed by ADB. Crises should not be used to push new reforms unrelated to the crisis when speed is critical, capacity is strained, and risks of weak country ownership are high.

Programmatic lending poses different challenges compared to stand-alone (single tranche) PBOs and pure budget support. The general need for development finance and greater flexibility drives demand for programmatic lending by low-income and some lower middle-income countries. Nevertheless, the use of programmatic PBOs has increased in nearly all MDBs during their evaluation periods and accounted for 30 to 40 percent of PBOs toward the end of this period.

Moreover, programmatic PBOs allow for more sustained engagement and, if policy measures become deeper as a programmatic series progresses, they can be useful to support reform programs, while also helping borrowers meet financing needs. However, over one-third of IDB’s programmatic PBL series approved since 2005 were truncated before reaching their most consequential reform steps, raising questions of ownership of the underlying reform programs. Truncation, however, was more pronounced for countries that did not seek technical assistance to go along with the underlying reform programs. The fact that programs supported by technical cooperation grants had a lower truncation rate indicates a need for continuous engagement and technical cooperation to support borrowing countries in their reform efforts. It also suggests that PBLs need to come with sustained policy dialogue and technical support.

v. Spurring private sector development should remain a central objective of PBOs.

A significant component of many PBOs has been improvement of the private sector environment, through financial sector reforms, capital market deregulation, and measures to strengthen public-private partnerships. Even reforms driven by fiscal concerns in sectors such as transport, energy, and water may include elements that improve the private sector environment.

Investment climate reform and economic diversification represented one-quarter to one-third of overall PBL value in World Bank PBOs. The share was larger in middle-income countries than in LICs. At IDB, the private and financial cluster (one of five clusters) averaged 17 percent of PBL commitments over 2005–19. At AfDB, diversification and industrialization, mainly through private sector environment reforms, were the leading PBO objectives across the issues identified in its strategies and action plans (under the “High 5s” explained in the AfDB chapter). Of the 16 operations given in-depth assessments, 9 related to the private sector environment. The budget support operations of the EU also include areas that affect the private sector environment and business confidence, such as DRM and trade.

Improving the private sector environment is a slow process. A 2019 assessment of World Bank development policy operation (DPO) support to Jamaica under an Economic Stabilization and Foundations for Growth loan found an unrealistically short period for the implementation of the business environment measures. The lag in the private sector response to even successful reforms, particularly when legislation is required, tends to lengthen the required time horizon. The ability to see the full outcome of policy reforms in the short term further complicates evaluation.

vi. Strengthening the macroeconomic framework, including agency coordination, is important for effective PBO support for growth and poverty reduction strategies.

MDBs need to coordinate with the International Monetary Fund (IMF), especially in large emergency financing packages, and evaluations of PBOs should examine the extent to which the supported policy reforms incorporate structural benchmarks in IMF-supported programs. However, the stance taken on this differs across the MDBs. It is useful to show not only PBL disbursements (flows) but also PBL stocks. Doing so can reveal whether PBL activity is essentially refinancing (disbursements that compensate for amortizations falling due) rather than increasing exposure, and how consistent it is with debt sustainability assessments. Why some MDBs focus so much on disbursement flows and pay little attention to exposure (stocks) requires more attention. Moreover, budget financing needs rather than balance of payments needs increasingly dominate PBL demand for most MDBs. This deserves assessment as it seems to challenge the view of MDB lending as a means to close a country’s external financing gap through burden-sharing with the IMF.

In general, the MDBs rely heavily on the IMF for macroeconomic assessments and in some institutions this is accepted with little further examination. ADB, for example, does not independently consider the adequacy of the macroeconomic framework at project completion, and the appropriateness of budget support is taken as given when supported by an IMF assessment letter. ADB’s Independent Evaluation Department challenges this, arguing that ADB must independently bear the risk implied by IMF assessments.

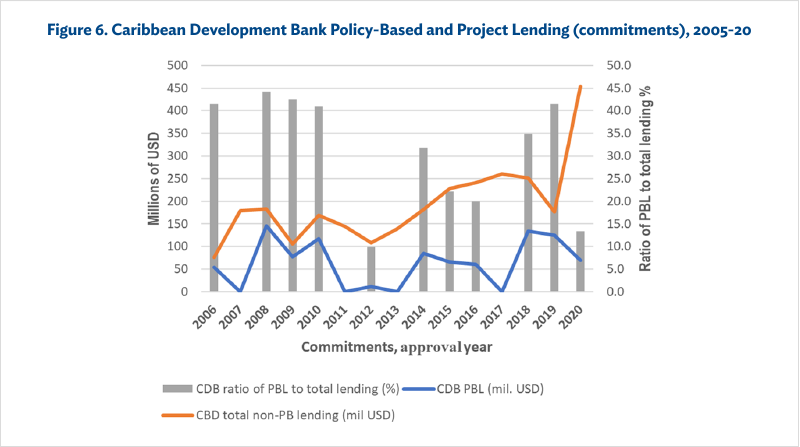

Staff members of the Caribbean Development Bank (CDB) are required to assess the adequacy of the macroeconomic framework for the conduct of a PBO, and the views of the IMF or the existence of an IMF program are critical ingredients in the appraisal. However, independent evaluation of the CDB’s stance recommended that greater collaboration with the IMF, World Bank, and IDB is needed for designing and implementing PBOs. Moreover, the evaluation recommended that PBOs not be provided to borrowing members without either an IMF stand-by arrangement or an IMF opinion on the adequacy of a home-grown program of adjustment.

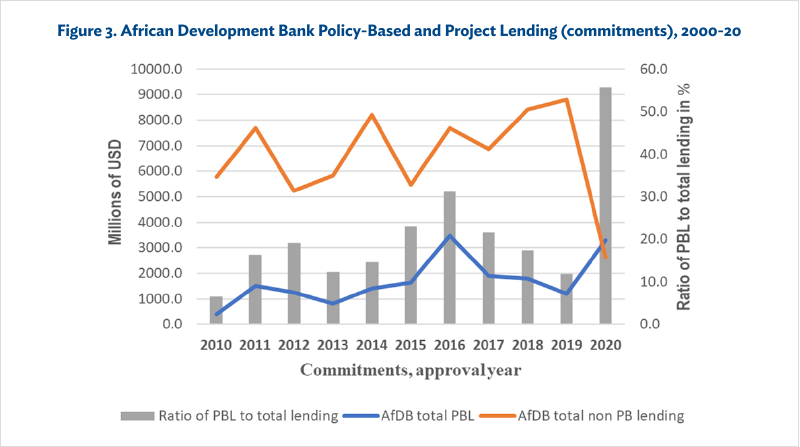

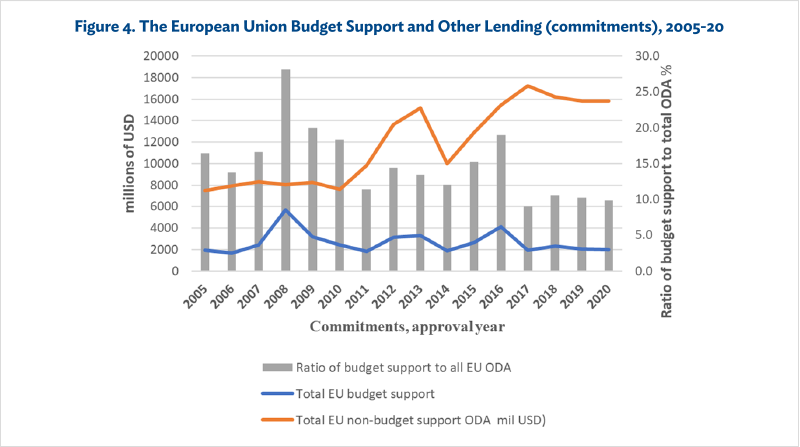

AfDB officially aligns itself with G-20 principles for coordination, working with other agencies and following the IMF assessments and World Bank analyses for countries facing macroeconomic vulnerability. The evaluation concludes that in four-fifths of cases AfDB coordination with other institutions on macro management is satisfactory. Such close coordination with other agencies also characterizes EU support through PBOs, but decisions on new budget support programs and payments are not bound by IMF positions. The EU has signed a partnership program with the IMF on the global architecture and policy agenda for PFM, domestic revenue mobilization (DRM), and transparency.

By contrast, since the mid-2000s, IDB has gradually expanded its analysis of countries’ macroeconomic frameworks and reduced its dependence on the IMF’s views. IDB required its regional departments (supported by IDB’s Research Department) to produce a macroeconomic assessment at the time of approval and disbursement of PBOs. In 2014, IDB took further action to decouple its PBL lending from the IMF’s assessment of macroeconomic conditions by no longer making PBL lending conditional on an on-track IMF program, Article IV consultations report, or macroeconomic update.IDB’s Office of Evaluation and Oversight has not evaluated the impact of the independence of macroeconomic assessment on PBO performance.

Finally, an independent IEG assessment of the quality of World Bank macro-fiscal frameworks in PBOs found they were internally consistent and had improved over time. In many cases, quality was related to the alignment of the macro-fiscal analytical work of the IMF and the World Bank. PBFs and IMF programs were complementary, supporting a sound macroeconomic framework, particularly fiscal and debt reforms. Coordinated support with development partners, particularly the IMF, helped support reform implementation, including inviting IMF inputs, especially during crises. During the COVID-19 crisis there has been close coordination, with the IMF providing emergency funding by doubling two rapid financing facilities, and the World Bank approved over $10 billion in operations to support vaccine rollout in 78 countries alongside large PBO commitments. Complementarity with IMF programs was associated with stronger outcomes for fiscal and debt-related operations. The analytical underpinnings of fiscal and debt-related PBFs influence the quality of their design. Debt and fiscal sustainability reforms are typically informed by Debt Sustainability Analyses; Debt Management Performance Assessments; Public Expenditure Reviews; and various technical assistance products.

At the same time, an independent evaluation of World Bank lending found weaknesses in three areas: (a) the ambition of macro-fiscal frameworks in some stand-alone operations and in the links between objectives and fiscal measures; (b) the credibility of the framework in view of the government’s record, political economy factors, treatment of risks, or institutional fiscal rules; and (c) the robustness of the debt sustainability analysis.

vii. Small island developing states and post-conflict and fragile states face challenges that require PBO assistance targeting their specific development needs.

The CDB is unique among MDBs in that its clients consist overwhelmingly of small states, defined as countries with fewer than 1.5 million inhabitants. Of the CDB’s 19 borrowing member countries, 17 are small states (or dependencies). Of the latter, most are islands or archipelagos. Similarly, ADB provides support to 14 Pacific island countries, most of which are small island developing states, with populations well below 250,000. The small states, especially island states, share some unique characteristics and challenges:

- High fixed costs of operations

- High levels of public expenditure, including public sector wage bills as a share of gross domestic product (GDP)

- High trade costs

- Extreme vulnerability to natural disasters and the effects of climate change

- Very concentrated exports (tourism, a few commodities), which leave them particularly vulnerable to trade shocks and contagion from downturns in trading partners

- The small absolute (though not relative) size of their public sectors limits their institutional capacity for policy making and service delivery.

CDB has raised its prudential limit to 38 percent to create lending headroom to counter the fallout from COVID-19 and offered exogenous shock response PBOs as a distinct instrument variant. The financing of emergency priority spending has helped preserve stability in CDB member countries. Future evaluations of PBOs can yield lessons on how effectively such operations have supported small states, built resilience, and helped mitigate shocks.

Regarding post-conflict and fragile states, the EU recently introduced a budget support instrument, the State and Resilience-Building Contract (SRBC), to address the complex and volatile environments fragile states face. They constitute about 10 percent of EU budget support contracts and proved very effective in the Ebola crisis and the COVID-19 pandemic. The requirements for access to SRBCs are less demanding than those of other EU instruments, letting fragile states qualify.

Given the condition of governments and their weak capacity in fragile settings and conflict-affected states, the focus on budget resource transfers directly to the government treasury, together with policy dialogue aimed at strengthening government capacity, is viewed by some as misplaced. More attention by development partners to addressing needs of the private sector in fragile states is needed to help strengthen markets, particularly where many basic services are delivered by nonstate actors.

There were many examples of how AfDB coordinated with other development partners, notably during the identification and appraisal periods, investing upfront work with other development partners. However, the in-depth assessment illustrated how difficult AfDB had found it to sustain these initial high levels of coordination throughout the implementation phase. Moreover, following the adoption of the G-20 Principles for Effective Coordination between the IMF and MDBs on PBL in 2017, the MDBs need to align behind the IMF in countries facing macroeconomic vulnerability.

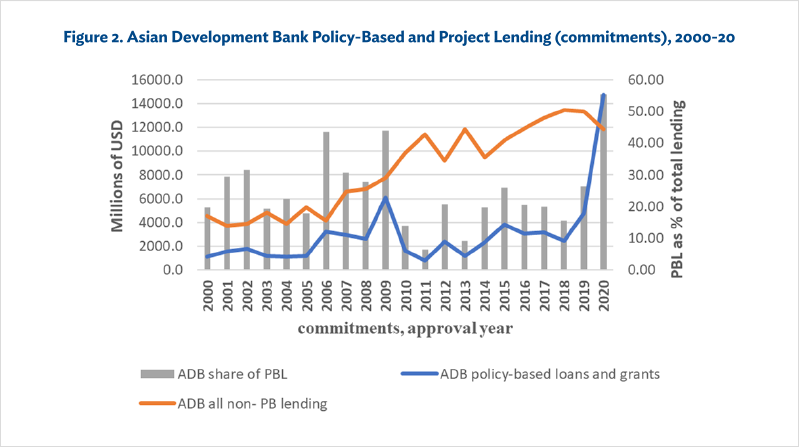

The use of PBL by ADB in the Pacific region appears to be linked to crisis years—the Asian financial crisis (1997), the dot-com bubble (2001), and the global financial crisis (2007–09). Recently, ADB has used PBL to provide contingent financing operations in some Pacific islands,which have been used to build disaster resilience during noncrisis times and to release funds immediately following a natural disaster. Still, given the scale of ADB investment in the development of infrastructure in the energy, water, and transport sectors in Asia and the Pacific, there is a notable lack of PBL-supported reforms in these sectors, even though infrastructure gaps were identified as key constraints on growth and poverty reduction in ADB’s long-term strategic framework.

In the EU (under its SRBC program), technical assistance was often used but was not the main driver in its programs. Most programs planned for technical assistance to strengthen governments’ weak institutional capacities, but with little coordination among development partners and only a weak connection with the programs, the technical assistance was merely able to provide limited knowledge transfer or follow-up actions. Several evaluations made the point that the EU and other development partners need new types of partnerships with countries, using cooperation modalities and tools in a different manner.

In sum, some low-income states and many fragile states are caught in a “fragility trap,” for which incremental solutions based on the principles used for higher income and non-fragile states are unlikely to be sufficient to help them escape. To manage such an escape, some of these countries will need much more aid than projected based on standard macroeconomic formulas. They will also need strong, continuous technical assistance to underpin and strengthen the policy dialogue.

viii. PBOs widely embrace improving governance and institutions, especially for public financial management, but performance depends on committed country counterparts.

In recent decades, PBOs increasingly have recognized the importance of governance and robust institutions for development outcomes. This has been evident in prior actions related to governance, most notably on PFM. This reflects a key concern that PBO funds are being used appropriately for development purposes given the fungibility of aid. Programmatic PBOs are often built around medium-term expenditure frameworks focused on budget formulation, execution, and audit and less focused on advancing infrastructure or removing major constraints to growth. This is consistent with thematic evaluations at the World Bank, which emphasized the prevalence of prior actions related to PFM.

Managing public finances is an important and powerful responsibility of government that affects the distribution of resources and the effectiveness of public programs. But other areas of governance reform, such as election systems, public employment, direct anticorruption efforts, may be as or more important for development outcomes. They have been more difficult for the MDBs to address given the challenging political environments that often prevail, limiting the kinds of program design and prior actions that are possible in PBOs. This underscores the overwhelming importance of committed country counterparts for achieving outcomes and is consistent with the World Bank finding that PBOs are significantly and positively correlated with the quality of social policies and institutions.