Historical Development and Use of Policy-Based Lending, 2005–2019

Summary

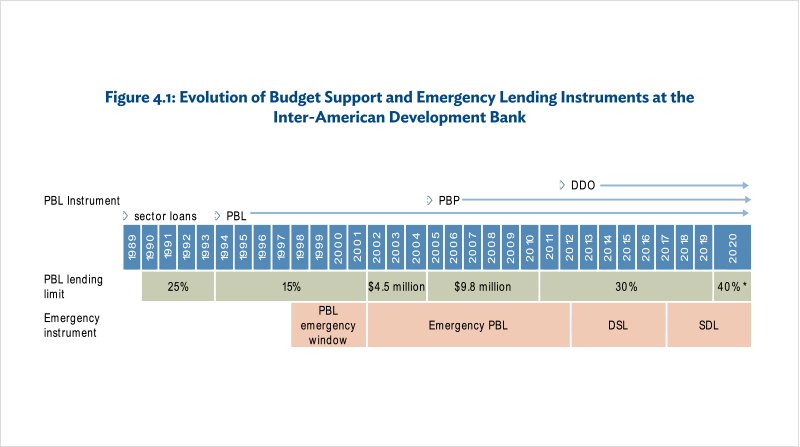

The Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) introduced policy-based lending (PBL) in 1989, in response to the Latin American and Caribbean debt crisis. The instrument has evolved over time, leading to a decoupling from International Monetary Fund (IMF) support, and the introduction of a programmatic variant (consisting of a series of single-tranche loans in support of a reform program) and of a deferred draw-down option. Policy-based lending has historically been subject to a lending limit which has changed over the years. In 2005–2019, policy-based lending accounted for about 28% of IDB’s sovereign-guaranteed approvals, with the share increasing over the period. All borrowing member countries except one used policy-based loans to varying degrees in the period. IDB’s policy-based loans are rarely co-financed by other institutions and IDB tends to support reform processes in areas in which it has accumulated experience and knowledge. Emergency budget support has been provided through separate budget support instruments that have also evolved over time. This form of support accounted for only 2% of sovereign-guaranteed approvals in 2005–2019. During the first half of 2020, in response to the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic, policy-based, and emergency budget support lending have spiked.

Background

IDB offers three broad lending categories among its sovereign-guaranteed loans. Investment lending (INV), policy-based lending (PBL), and lending for financial emergencies during macroeconomic crisis, called special development lending (SDL). In addition, IDB can also guarantee loans made by private financiers for public sector projects. PBL provides fast-disbursing financial assistance or country budget support that is conditional on the borrowing country fulfilling a set of agreed upon policy and institutional reforms, while investment loans disburse against specific predefined project expenditures. SDLs also provide fast-disbursing support and are conditional on a country having been struck by a macroeconomic crisis, being supported by an active IMF program, and the SDL being part of an international support package.

IDB introduced PBL at the time of its seventh capital replenishment in 1989, in response to the Latin American and Caribbean (LAC) debt crisis of the 1980s. It was based on the model of conditional budget support created by the World Bank almost a decade earlier. Originally called sector loans, IDB’s PBL was intended to support the twin objectives of promoting policy or institutional reform and helping countries meet their financing needs. PBL was introduced to help countries pursue macroeconomic adjustment programs while supporting structural reforms. PBL was to be disbursed in several tranches and was conditioned on the maintenance of a sustainable macroeconomic policy framework and compliance with a set of agreed-upon conditions defined in a policy matrix. PBL processes required a country policy memo to ensure that the conditions were being complied with and relied on IMF-supported programs for macroeconomic assessments. Policy-based lending was capped at a maximum of 25% of IDB’s 1990–1993 overall lending program. By the time of its eighth capital replenishment in 1994, IDB concluded that the need for major macroeconomic adjustment in the Latin America and Caribbean region had declined and that PBL should place greater emphasis on social sector policy and the efficiency of service delivery. To reflect this, the term sector loans was changed to policy-based loans and the cap was reduced from 25% to 15% of the lending program. The effects of the Asian financial crisis in 1997–1998 made adhering to the new cap difficult and led to the introduction of a transitory emergency variant of PBL, which was subject to a separate limit. The emergency program ended in the early 2000s, but demand for PBL continued to exceed the 15% limit. This led to three modifications in 2002: the 15% ceiling was replaced by an absolute figure of $4.5 billion for 2002–2004 (meaning that PBL lending became independent from the level of investment lending);1a new emergency lending category, now separate from PBL, was introduced; and a minimum disbursement period of 18 months across tranches was established for PBL, mostly to avoid crowding out the new emergency instrument. Moreover, IDB started to supplement the traditional policy matrix with a matrix of results in its PBL loan documents.

By the mid-2000s, as borrowing countries were experiencing higher growth, increased institutional capacity, and better access to capital markets, IDB introduced three main changes to PBL. First, IDB made a progressive move to expand its own analysis of the adequacy of countries’ macroeconomic frameworks and reduce its dependence on the IMF’s views. This led to the creation of the “independent macroeconomic assessment,” which required the regional departments (supported by the Research Department) to produce a macroeconomic assessment at the time of approval and disbursement of PBL. In practice, however, IMF views continued to be a key input to IDB’s assessment.2Second, the 18-month minimum disbursement period for PBL was removed. Finally, a programmatic variant of PBL, called programmatic policy-based loan, was introduced. The programmatic version consists of a series of single-tranche operations set in a medium-term framework of reforms. The first operation identifies the policy conditions for that operation as well as indicative triggers for the subsequent loans in the series. Since the triggers can be revisited at the time of loan approval, programmatic PBLs allow for conditions to be adjusted as circumstances change. With these changes, IDB also approved guidelines for the preparation and implementation of PBL, thus consolidating existing policies and practices for the first time.

* temporary in response to COVID-19.

DDO = deferred draw-down option, DSL = development sustainability credit line, PBL = policy-based loan, PBP = programmatic policy- based loan, SDL = special development loan.

Source: Based on IDB Office of Evaluation and Oversight (OVE). Design and Use of Policy-Based Loans at the IDB. Document RE-485-6. Washington, DC: IDB. https://publications.iadb.org/en/ove-annual-report-2015-technical-note-design-and-use-policy-based-loans-idb

More recently, PBL lending limits have been raised further and a deferred draw-down option has been added. The dollar-denominated cap on PBL established for 2005–2008 was initially extended for 2009–2012, but in 2011 the ceiling for PBL was changed to 30% of total approved lending. More recently, to facilitate IDB’s response to the COVID-19 crisis, the ceiling has been temporarily increased to 40% of total lending through 2022.3In 2012, IDB also introduced a deferred draw-down option (DDO) to synchronize proceeds with countries’ financing needs. The DDO allows countries, on payment of an up-front premium, to draw on the resources of PBL when they require these funds. During the drawdown period, the borrower must maintain policy conditions and sustainable macroeconomic policies. In 2014, further actions were taken to decouple IDB’s PBL lending from the IMF’s assessment of macroeconomic conditions. IDB decided to strengthen its own macroeconomic assessment capacity and no longer make PBL lending conditional on an on-track IMF program, Article IV, or IMF letter of comfort.

On the emergency lending side, a temporary emergency lending facility was replaced by a consecutive series of emergency lending instruments. The initial temporary emergency facility established in response to the 1997–1998 financial crisis was replaced by a permanent emergency lending category in 2002. It was capped at $6 billion and was in turn replaced by a development sustainability credit line in 2012. This was a contingent credit line whose funds could be withdrawn at a time of a crisis, but it had to be approved before the crisis. It was geared toward providing liquidity during financial distress, while protecting expenditures for programs directed at the poor. It expired in 2015 and was replaced by the special development lending (SDL) instrument in 2017. While the SDL does not require an IDB-specific independent macroeconomic assessment, it is conditional on a country experiencing a macroeconomic crisis and being supported by an existing IMF program. SDL lending cannot exceed $500 million or 2% of a country’s GDP if supported by fresh funds. It can be funded through a reallocation of uncommitted loan balances, provided at least 60% of the remaining uncommitted loan balances are investment loans.

- 1Three years later that limit was increased to $9.8 billion for 2005–2008, and for the first time a cap was established on disbursements—$7.6 billion for the 4-year period. A ceiling on concessional PBL from the Fund for Special Operations (FSO) was also established ($100 million for the 4-year period).

- 2An IMF on-track program or Article IV (issued within the last 6 months) were de facto requirements to approve and disburse a PBL operation. If an Article IV was more than 6 months old, or if the country had no IMF program or Article IV in place, a letter of comfort from the IMF was usually required.

- 3The PBL lending cap of 30% of total lending applies to lending from IDB’s ordinary capital over consecutive four-year periods. For concessional lending from the FSO the cap is applied on a biannual basis. The temporary increase of the cap to 40% of total lending from the IDB’s ordinary capital applies to the 4-year period ending in December 2022. For FSO resources, the increased PBL cap of 40% applies to lending for 2021–2022.

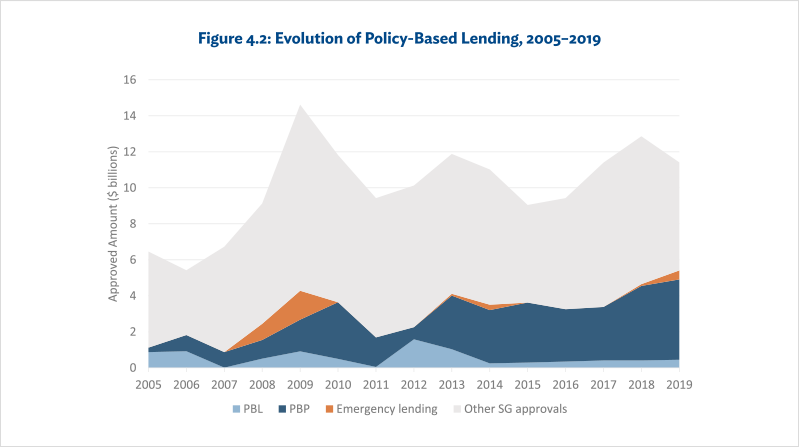

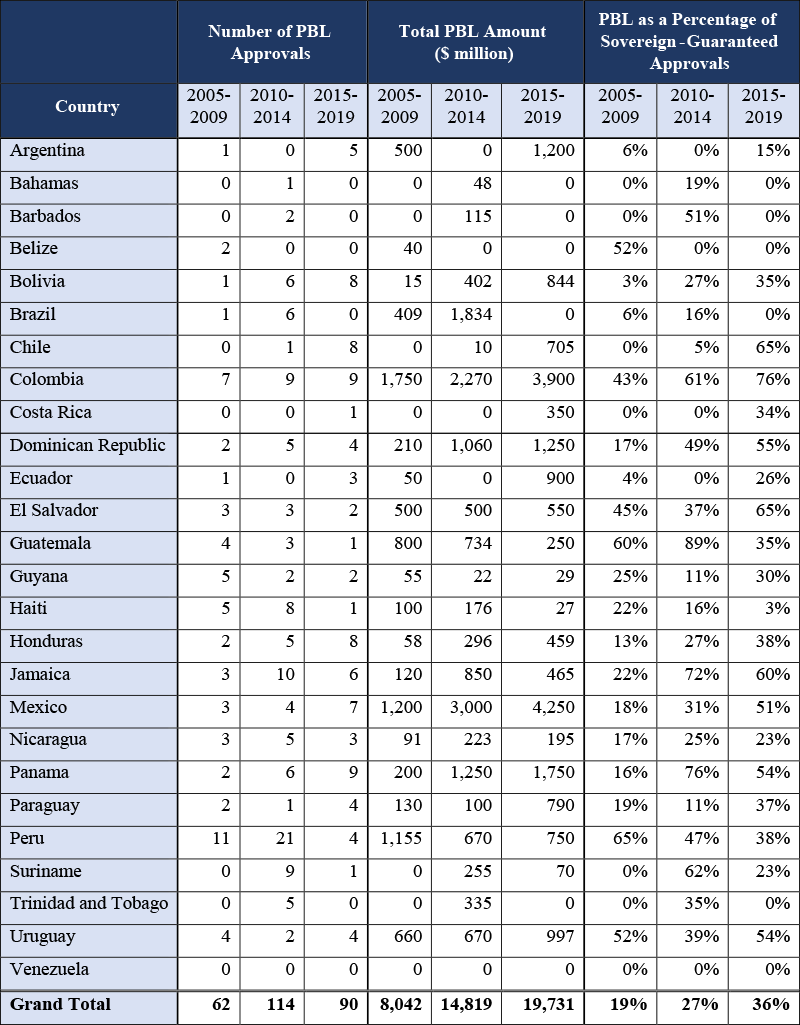

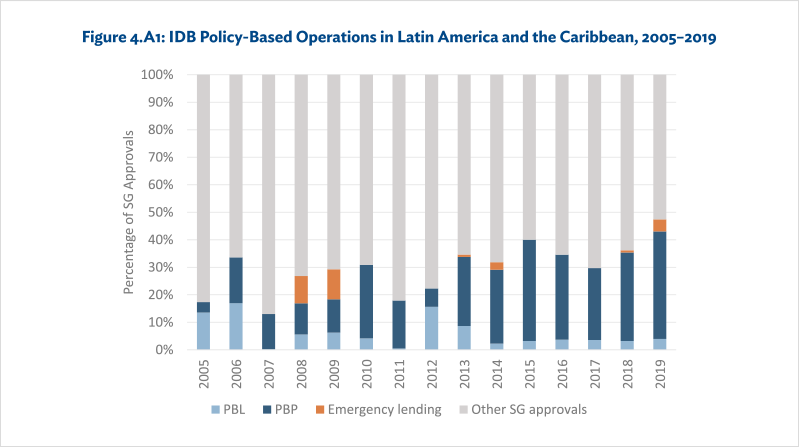

Evolution of Policy-Based Lending Portfolio

Between 2005 and 2019, policy-based operations accounted for 28% of IDB’s sovereign-guaranteed approvals4, with the share increasing over time. In this period, IDB approved 266 policy-based operations totaling almost $42.6 billion. About 80% of these resources were approved as programmatic operations supporting 124 programs, with the remaining 20% as individual single- or multitranche policy-based operations. Since 2007, programmatic PBLs have consistently accounted for at least three-quarters of all approved policy-based operations. Policy-based operations’ share of total sovereign guaranteed approvals increased from 19% in 2005–2009 to 36% in 2015–2019 (Table 4.2). The 2007–2009 global financial crisis led to a significant increase in the number and amounts of policy-based operations. IDB approved 61 policy-based operations for $7.9 billion in 2008–2010, compared with only 31 such operations for $3.8 billion during the previous 3 years. After falling somewhat in relative importance in 2011–2012, policy-based operations rose again in 2013 and since then IDB has averaged around 19 policy-based operations totaling almost $3.9 billion per year (Figure 4.2).

PBL = policy-based loan, PBP = programmatic policy-based loan, SG = sovereign-guaranteed.

Source: IDB Office of Evaluation and Oversight(OVE), based on data from IDB databases.

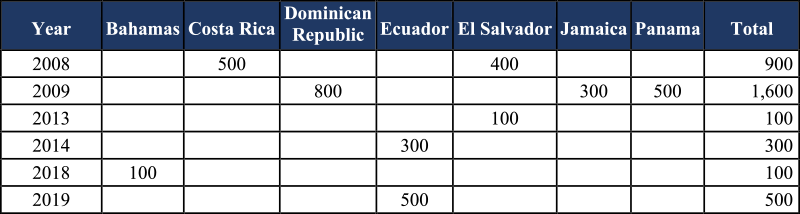

Emergency lending accounted for 2% of sovereign-guaranteed approvals between 2005 and 2019. Emergency lending to provide financial support during a macroeconomic crisis was primarily used during the 2007–2009 financial crisis. Five countries used this option, but three of the loans never disbursed and two disbursed only partially. Three countries also made use of emergency lending after the financial crisis to weather country specific crises (Table 4.1). Overall, IDB approved $3.5 billion in emergency lending between 2005–2019, of which 71% was approved in 2008-09.

Table 4.1. Emergency Lending, 2005–2019 ($ million)

Source: IDB Office of Evaluation and Oversight(OVE), based on data from IDB databases.

IDB’s PBL and emergency approvals spiked during the first half of 2020, in response to the COVID-19 pandemic and its economic effects. To facilitate timely approval of operations to help its borrowing member countries respond to the COVID-19 pandemic and related social and economic effects, IDB developed several prototype operations, including one for PBL in support of fiscal and economic management to help cushion the effects of the economic crisis. The PBL prototype sets out a menu of policy measures geared towards timely availability of resources to respond to the public health crisis, temporary expansion of social protection programs, provision of essential services, efficient public expenditure management and formulation of a program for economic recovery. Individual operations then draw on a menu of these measures for speedy preparation and approval. The prototype also includes a pro forma results matrix. During the first 7 months of 2020, IDB approved 14 PBL operations amounting to $4.18 billion, of which $1.2 billion went to five prototype operations. In addition, it approved five special development lending operations in the amount of $1.2 billion.

Cofinancing of IDB PBL has been minimal since the mid-2000s. Most of IDB’s PBL cofinancing occurred in the early days of PBL, especially in the first 2 years of the instrument’s existence when partnership with the World Bank was mandatory. Cofinancing remained important until the mid-2000s but since then IDB has financed almost all PBL on its own. Similarly, in the early years of PBL, operations used to be approved when the borrowing country had an IMF-supported program in place: 90% of the PBL approvals between 1995 and 2003 were granted to countries with an IMF program. This proportion has decreased substantially since then, both because of the decreasing presence of IMF-supported programs in Latin America and the Caribbean, and because of IDB’s progressive move to expand its own assessment of the adequacy of countries’ macroeconomic frameworks and reduce its dependence on the IMF’s views. There are, nevertheless, instances where IDB has continued to support PBL in the context of an IMF program, including for example $1 billion of PBL support to Argentina in 2018–2019.

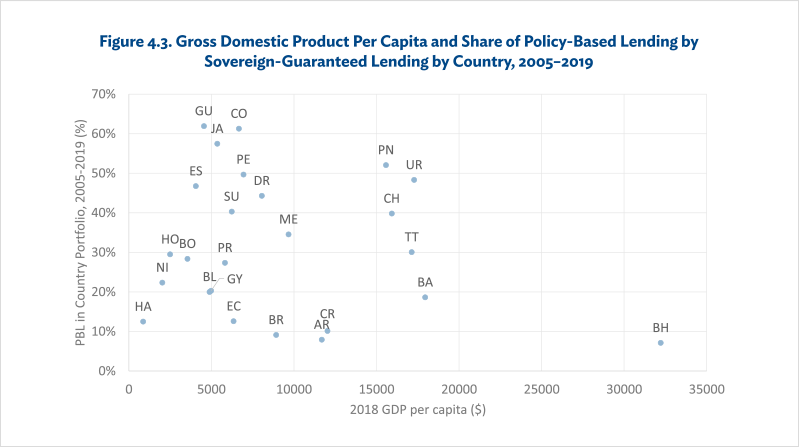

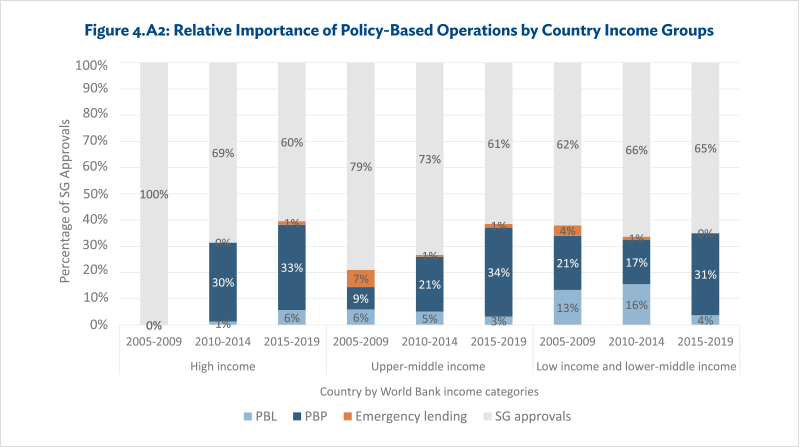

Apart from Venezuela, all borrowing member countries made use of PBL over 2005–2019, but the relative importance of PBL in country portfolios varied. The share of PBL in overall sovereign-guaranteed approvals increased for all country income groups and was not significantly correlated with country income level (Figure 4.3 and Annex, Figure 4.A2). In terms of overall importance, a few countries have dominated, both in the number and amounts of PBL received. Peru received 36 PBL operations and Colombia 25, reflecting their strong preference for the instrument. In terms of overall volume, Colombia and Mexico together accounted for almost 40% of the approved PBL volume over this time period (Table 4.2). Five countries (Colombia, Guatemala, Jamaica, Panama, and Peru) borrowed at least half of their sovereign-guaranteed envelope in the form of PBL in 2005–2019, and in the last 5 years eight countries did so (Chile, Colombia, Dominican Republic, El Salvador, Jamaica, Mexico, Panama, and Uruguay). Only two countries (Peru and Uruguay) have made use of the deferred draw-down option, with Uruguay using it as an important instrument for fiscal and foreign exchange management.

GDP = gross domestic product, PBL = policy-based lending. AR=Argentina; BH=Bahamas; BA=Barbados; BL=Belize; BO=Bolivia; BR=Brazil; CH=Chile; CO=Colombia; CR=Costa Rica; DR=Dominican Republic; EC=Ecuador; ES=El Salvador; GU=Guatemala; GY=Guyana; HA=Haiti; HO=Honduras; JA=Jamaica; ME=Mexico; NI=Nicaragua; PN=Panama; PR=Paraguay; PE=Peru; SU=Suriname; TT=Trinidad and Tobago; UR=Uruguay.

Source: IDB Office of Evaluation and Oversight (OVE), based on data from IDB databases.

Table 4.2. Policy-Based Lending Approvals by Country, 2005–2019

Notes: PBL = policy-based lending. Includes PBL funding from all sources.

Source: IDB Office of Evaluation and Oversight (OVE), based on data from IDB databases.

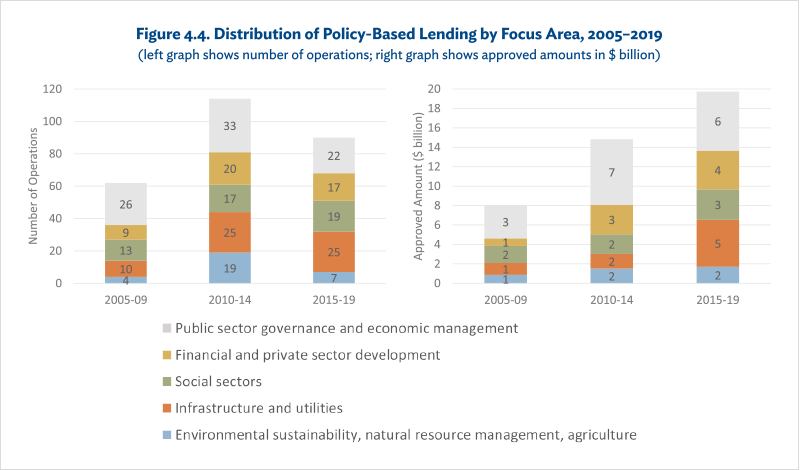

IDB classifies its loans based on their main sector focus. Based on this classification, this chapter has grouped the PBL approvals in 2005–2019 into five thematic areas:

(i)public sector governance and economic management;

(ii)financial sector reform and private sector development (with the latter mostly supporting measures to improve competitiveness);

(iii)social sectors (health, education, social protection and gender);

(iv) infrastructure and utilities (transport, energy, water and sanitation, housing and municipal infrastructure); and

(v) environment, natural resource, territorial and disaster risk management, and agriculture.

Both in terms of number of operations (30% of the total) and approval volumes (38% of the total), PBL in the area of public sector governance and economic management has dominated.5The importance of reforms supported in this area grew considerably in the face of the 2007–2009 global financial crisis. However, an analysis by the IDB Office of Evaluation and Oversight (OVE) found that the content of policy conditions did not change much compared with similar PBL operations approved before the crisis. Programs initiated in pre-crisis years (2005–2007) and crisis years (2008–2010) included similar conditions, which were usually oriented toward such areas as establishing fiscal rules, increasing government revenues or improving spending, and developing frameworks and systematic macroeconomic forecasting for budgeting.6

The second most important group contained PBL in support of infrastructure, with a particular focus on utility reforms, which accounted for 23% of operations and 18% of lending volume. This group grew considerably in importance over the review period, from only ten operations approved in 2005–2009 to 25 operations in 2015–2019, driven by support for energy sector reforms.

A more in-depth analysis of PBL by OVE suggests that IDB usually supports reform processes in areas in which it has accumulated experience and knowledge. In its 2015 review of the design and use of PBL at IDB, OVE mapped the interaction between PBL and a set of broader but related operations in each country, using social network analysis. The results suggested that IDB tended to support policy reforms in sectors in which it had previously worked (usually through technical cooperation grants or investment loans) and thus where it had some country-level expertise that allowed it to sustain policy dialogue and provide relevant technical advice. This finding is also compatible with the hypothesis that when countries need quick financial support, IDB turns to sectors where it has expertise so it can respond more quickly.

Source: IDB Office of Evaluation and Oversight(OVE), based on data from IDB database.

- 4Sovereign guaranteed approvals in this context includes all SG loan and guarantee operations regardless of funding source.

- 5Some PBL operations support reforms in multiple sectors. When assigning a sector code to an operation, IDB goes by the number of policy measures in a given sector and does not account for the fact that operations may cover several sectors. Hence the figures presented here may not give a full picture of all reforms supported in a given area.

- 6IDB Office of Evaluation and Oversight, <em>Design and Use of Policy-Based Loans at the IDB.</em> Document RE-485-6. Washington, DC: <a href = "publications.iadb.org/en/ove-annual-report-2015-technical-note-design-and-use-policy-based-loans-idb">https://publications.iadb.org/en/ove-annual-report-2015-technical-note-design-and-use-policy-based-loans-idbIDB</a>

Evaluation of Inter-American Development Bank Policy-Based Lending

Summary

In 2015, the IDB Office of Evaluation and Oversight undertook an analysis of the design and use of policy-based lending at IDB. Although it found countries used PBL for various reasons, the predominant use was for budget support in time of need. While countries valued the policy dialogue and technical expertise that came with IDB PBL, the policy elements were usually secondary to the primacy of budget support. Although PBL provided important financial support, its ability to play a countercyclical role overall was limited because of the cap on PBL and because PBL could not be disbursed if borrowers did not have a positive macroeconomic assessment. The review assessed the depth of the policy conditions and found that most were of low- or medium-depth, meaning they helped set in motion policy reforms but could not by themselves effect lasting changes. Conditions tended to gain in depth in the second and third loan of a programmatic series, as the underlying reform program progressed. However, over one third of programmatic PBL programs active in 2005–2019 were interrupted, affecting the depth of supported programs. Policy conditions were of higher depth in programs in the financial and energy sectors and during times of crisis. Neither the number of conditions in a program nor the loan size were correlated with program depth

Background

OVE has looked at PBL in several contexts, but a full-fledged evaluation of IDB’s policy-based lending has not been undertaken to date. OVE routinely reviews the performance of PBL in the context of its country program evaluations. OVE also reviews and validates IDB’s self-evaluations of completed programs and operations and assigns a performance rating to each completed PBL program or freestanding PBL operation. In addition, OVE undertook a thorough review of the design and use of PBL in 2015.7This section will briefly discuss the performance ratings of PBL based on OVE’s validations of self-evaluations and then present key findings of OVE’s 2015 review of the design and use of PBL.

IDB’s current self-evaluation system was adopted relatively recently. Project teams are required to prepare a project completion report for a programmatic PBL series when the program has been completed or interrupted or, in the case of freestanding PBL operations, at the time of completion of the operation. These self-evaluations are then validated by OVE which assigns an outcome rating to each program or freestanding PBL operation. In the case of programmatic PBL series, the program as a whole is evaluated against a results matrix for the entire program rather than for each loan. In the case of a freestanding PBL, the operation is assessed against the results matrix for that particular operation. The assessment covers three dimensions: relevance, effectiveness, and sustainability. An overall performance rating is assigned based on a weighted average of the ratings achieved on each of these three dimensions.8As this system has evolved over time, comparable performance ratings are available for only 4 years; for operations or programs that were validated by OVE in 2017–2020. A total of 26 programs, comprising 48 loans have been rated thus far. Four of these consisted of hybrid operations with a PBL and an investment lending component. Of the 26 validated programs, 15 (58%) achieved an overall outcome rating of partly successful or higher. Excluding the hybrid operations, 14 of the 22 programs (64%) achieved a rating of partly successful or higher (compared with 57% of investment loans).

- 7IDB Office of Evaluation and Oversight, <em>Design and Use of Policy-Based Loans at the IDB</em>. Document RE-485-6. Washington, DC: IDB<a href="//publications.iadb.org/en/ove-annual-report-2015-technical-note-design-and-use-policy-based-loans-idb"> https://publications.iadb.org/en/ove-annual-report-2015-technical-note-design-and-use-policy-based-loans-idb </a>

- 8Relevance, effectiveness and sustainability are each rated on a four-point scale. The overall performance rating is a weighted average of the scores on each of these three dimensions, with relevance and sustainability being given a weight of 20% each and effectiveness 60%. The overall performance rating uses a six-point scale ranging from highly successful to highly unsuccessful.

Findings of the Review

Among the key questions that OVE’s 2015 review of the design and use of PBL explored were how the design and implementation of PBL operations changed over time and why countries demand PBL. The following sections will briefly summarize the review’s findings in this respect. OVE’s 2015 analysis did not seek to evaluate the achievements of the outcomes to which the PBL sought to contribute. It covered the period 1989–2014, with an emphasis on the last decade of the period.

Why did Countries Demand Policy-Based Lending?

To explore what drives countries’ demand for PBL, OVE looked at four dimensions: (i) the frequency and intensity of PBL use; (ii) the correlation between PBL borrowing and growth rates, fiscal deficits, and gross financing requirements; (iii) countries’ reliance on parallel technical cooperation grants; and (iv) countries’ tendencies to fully complete or interrupt (“truncate”) programmatic PBL series. OVE analyzed these dimensions by reviewing all relevant lending documents and country economic data, carrying out an econometric analysis of lending, and interviewing IDB staff and officials from borrowing countries. Through this analysis, OVE identified four main categories of PBL users (Box 4.1).

- Mostly as budget support. This category included countries that resorted to PBL mainly in a countercyclical fashion (for example, to deal with a crisis that had suddenly halted capital inflows) or as a swift source of liquidity to handle short-term needs, such as debt servicing. In general, these countries exhibited a negative correlation between policy-based lending and GDP growth rates, and a positive correlation between policy-based lending and fiscal deficits or gross financing requirements. Their programmatic PBL series exhibited relatively high rates of interruption. They did not rely much on parallel IDB technical cooperation grants to accompany the reform programs. Since their demand for PBL depended on economic needs, these countries were not among the most regular users of PBL. In the decade leading up to 2015, examples in this category included Dominican Republic, Honduras, and Jamaica.

- Mostly as seal of approval for reforms and to benefit from IDB’s technical advice. This group comprised countries that tended to resort regularly to PBL and did so mostly to help legitimize their policy reform process by getting a “seal of approval” from IDB and to benefit from technical discussions between country officials and IDB specialists. Their PBL operations tended to be relatively small, and the demand for PBL tended not to be correlated with growth, fiscal deficits, or gross financing requirements. Moreover, programmatic PBL series in these countries had low truncation rates (a reflection of reform program implementation over a more extended time period and arguably higher ownership of the underlying reform program). They relied significantly on parallel technical cooperation grants provided by IDB to support the PBL programs. Peru and Bolivia were examples of this country grouping.

- Mixed. These countries sometimes relied on PBL to cover financing needs and sometimes used them to benefit from IDB’s validation and technical inputs. Examples in the decade leading up to 2015 included Brazil, Colombia, Mexico, El Salvador, Nicaragua, and Panama.

- Preventive. Uruguay has used policy-based lending as part of the government’s precautionary borrowing strategy with multilateral development banks (MDBs). Since 2008, Uruguay has frequently postponed disbursements of approved PBL and used the proceeds only when it faced large financing needs. This practice was institutionalized with IDB’s introduction of the DDO modality in 2012. Recently, Uruguay resorted to drawing down resources from several DDO PBL operations to rapidly cover its financing needs to counter the COVID-19 pandemic and its associated social and economic effects.

Box 4.1. Rationale for Policy-Based Lending: Selected Cases

Jamaica and the need for budget support. More than half of Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) support for Jamaica in the decade leading up to 2015 was in the form of PBL, which helped the country advance public financial management and social reforms in the context of two IMF adjustment programs. Disbursements to Jamaica in 2010 in support of the first of those IMF programs (about $600 million) were among the largest IDB had provided to a borrowing country in a single year, both in per capita terms and as a share of GDP.

Peru’s regular use of PBL and IDB’s “seal of approval.” Peru stood out as the most regular user of PBL: it had 43 PBLs between 1990 and 2014, and 32 of them were approved in the decade leading up to 2015. Uniquely among IDB borrowers, Peru had at least one PBL approved every year between 2000 and 2015. The 32 PBL operations approved between 2005 and 2014 were arranged in 11 programmatic series. Most were long series (three or four loans each), supported by several technical cooperation grants, and all of them were completed—another feature that distinguishes Peru from many other IDB borrowers. However, each loan was relatively small. Peru used PBL to legitimize institutional reforms and obtain technical expertise through strong parallel technical cooperation grants, in a context of favorable fiscal results.

Colombia’s flexible use of programmatic PBL series. Colombia stood out for its heavy use of PBL, with 22 such operations approved between 1990 and 2014. Sixteen of these were approved between 2005 and 2014, accounting for more than half of the sovereign-guaranteed lending approved for the country over the period. The intensive use of PBL was the result of Colombia’s demand for funds to meet its annual fiscal and debt commitments, and to stimulate the economy when needed. This might help explain why Colombia’s programmatic PBL series were frequently interrupted. That said, Colombia also used PBL because it valued IDB’s technical support and it was a frequent user of parallel technical cooperation grants, which usually provided strategic inputs for the reform processes.

Panama’s recurrent shift in program focus. As in Peru and Colombia, IDB’s engagement with Panama pivoted on PBL: in the decade leading up to 2015, over 40% of all sovereign-guaranteed lending, and over 70% during the second half of the decade, was PBL. These operations were instrumental in providing policy advice to support Panama in building a strong macroeconomic policy framework, but PBL also became a regular (and reliable) source of government funding. As in Colombia, this might help explain why the programmatic PBL series in Panama were frequently interrupted. Successive changes in the focus of IDB’s programmatic lending prompted the truncation of most of Panama’s series in 2010–2014. As a consequence, five of 11 planned operations did not materialize, thus diminishing the relevance of the proposed lending series.

Support for subnational fiscal consolidation in Brazil. Until the early 2000s, Brazil hardly used PBL. Six of eight Brazilian PBL operations approved through 2014 were approved between 2012 and 2014. All of them supported reforms at the subnational level. Brazil’s use of PBL at the subnational level is unique among IDB borrowers.

Uruguay’s preventive use of PBL. Uruguay made use of a limited number of relatively large PBL operations as a liquidity management tool. Even before IDB introduced a deferred draw down option (DDO) in 2012, Uruguay opted to delay drawing down the proceeds of two PBL operations until December 2008 and January 2009, after the collapse of Lehman Brothers, when the external cost of financing in the market had substantially increased. Since the introduction of the DDO in 2012, Uruguay has made frequent use of this option.

DDO = deferred draw down option, IDB = Inter-American Development Bank, PBL = policy-based lending.

Source: Based on IDB Office of Evaluation and Oversight (OVE). Design and Use of Policy-Based Loans at the IDB. Document RE-485-6. Washington, DC: IDB.https://publications.iadb.org/en/ove-annual-report-2015-technical-note-design-and-use-policy-based-loans-idb

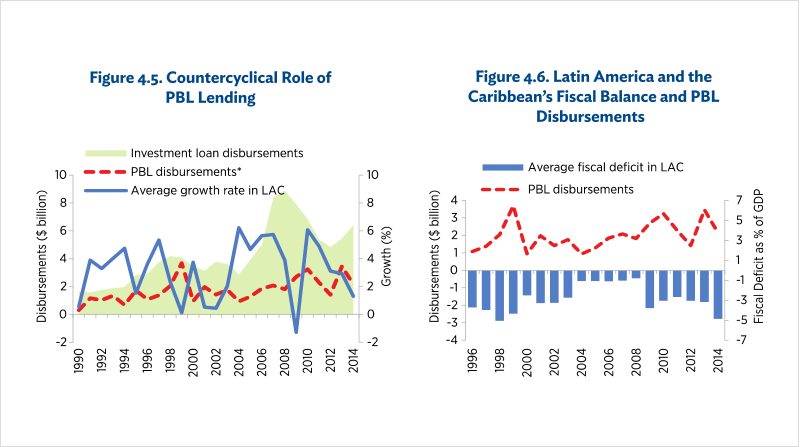

Overall, OVE concluded that, despite the range of reasons for using PBL across countries, the predominant use was for budget support in time of need. Its review found that, while countries valued the policy dialogue and technical expertise that came with IDB PBL, the policy elements were usually secondary to the primacy of budget support. Econometric analysis found that policy-based lending was negatively correlated with a country’s growth rate, and positively correlated with the size of fiscal deficits and gross financing needs (Figure 4.5, Figure 4.6). Drawing on the literature on early warning signals for economic and financial crises, OVE estimated fixed-effects panel regression models using PBL disbursements as a percentage of GDP as the dependent variable. The results confirmed that countries’ financing objectives were a key motivation for the use of PBL, both to handle short-term financing needs and to face contingent shocks. The use of PBL for budget support purposes was found to be particularly pertinent for small economies, which tended to be more vulnerable to external economic shocks and for which IDB financing could be decisive in helping them to weather a storm. While larger countries also made use of PBL for fiscal and liquidity management purposes, the instrument’s ability to affect macroeconomic conditions in these countries was limited by the small size of the loans in relation to their overall economies. While PBL played a major financing role, its countercyclical role overall was limited in most countries by the overall cap on PBL and the fact that PBL could not be disbursed if borrowers did not have a positive macroeconomic assessment.

An analysis of the extent to which PBL funding is complementary or a substitute for market financing was beyond the scope of OVE’s 2015 review and therefore remains an open question. OVE country program evaluations suggest that some countries with ample access to international financial markets tend to use PBL as a debt and liquidity management tool to complement market financing, particularly when borrowing during good economic times. A Colombia country program evaluation, for example, found that, as the country gained increased access to financial markets, PBL remained an attractive instrument because its large and predictable disbursements facilitated the Ministry of Finance’s financial planning, given that Colombia tended to issue bonds in January and September. Similarly, a recent evaluation of Mexico’s country program found that the Ministry of Finance sought regular and predictable disbursements for debt management purposes.9

GDP = gross domestic product, LAC = Latin America and the Caribbean, PBL = policy-based lending.

Source: IDB Office of Evaluation and Oversight (OVE). Design and Use of Policy-Based Loans at the IDB. Document RE-485-6. Washington, DC: IDB.https://publications.iadb.org/en/ove-annual-report-2015-technical-note-…

- 9IDB Office of Evaluation and Oversight (OVE). 2015. <em>Country Program Evaluation: Colombia 2011-2014</em>. Washington, DC: IDB. <a href="//publications.iadb.org/en/country-program-evaluation-colombia-2011-2014">https://publications.iadb.org/en/country-program-evaluation-colombia-2011-2014; </a> IDB Office of Evaluation and Oversight (OVE). 2019. <em>Country Program Evaluation: Colombia 2015-2018</em>. Washington, DC. IDB<a href="//publications.iadb.org/en/country-program-evaluation-colombia-2015-2018"> https://publications.iadb.org/en/country-program-evaluation-colombia-2015-2018;</a> IDB Office of Evaluation and Oversight (OVE). 2019. <em>Country Program Evaluation: Mexico 2013-2018</em>. Washington, DC. IDB<a href="//publications.iadb.org/en/country-program-evaluation-mexico-2013-2018"> https://publications.iadb.org/en/country-program-evaluation-mexico-2013-2018</a>

How did the Design and Implementation of Policy-Based Lending Change over Time?

OVE’s analysis of the design of PBL focused on the evolution and nature of policy conditions, the vertical logic of the programs, and the extent to which PBL was accompanied by other IDB support. When looking at the evolution of policy conditions, OVE considered all PBL operations approved between 1990 and 2014, in order to gain a longer-term perspective. For a more in-depth analysis of the nature of policy conditions, and the complementarity between PBL and parallel IDB support, OVE focused on PBL operations approved in the decade leading up to 2015. In order to conduct this analysis, OVE drew a stratified random sample of 40 policy-based programs from the universe of PBL operations approved between 2005 and 2014 in four thematic areas: public sector and economic management, social sectors, financial sector, and energy. The sample encompassed 70 multitranche and programmatic loans in 18 countries and covered 34% of all programs approved over the time period. Analysis of policy matrices was supplemented by information from pertinent OVE country program evaluations and interviews with IDB staff and country stakeholders. To review the complementarity between PBL and parallel IDB support through technical cooperation grants or investment loans, OVE focused on all 82 programmatic PBL series (equivalent to 144 PBL operations) approved between 2005 and 2014.

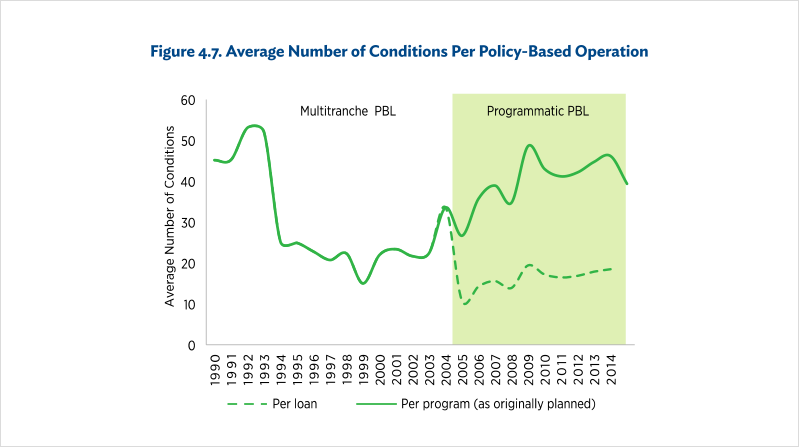

The number of conditions at the program level increased over time. In the early 1990s, the average number of conditions per loan was roughly 50, and that figure fell by half between the mid-1990s and 2004. In line with the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Paris Declaration in 2005, the introduction of the programmatic modality further streamlined conditionality at the loan level (Figure 4.7). However, at the program level, the average number of conditions increased after 2005, offsetting the streamlining gained at the loan level10. There were no significant differences in the number of conditions across thematic areas or regions.

PBL = policy-based lending.

Note: The graph shows the average number of conditions per multitranche policy-based loan for 1990–2004, and per programmatic PBL series from 2005 onwards, at both the loan and the program level (as originally expected). Figures at the program level are based on the programmatic PBL series’ initial year.

Source: IDB Office of Evaluation and Oversight (OVE).Design and Use of Policy-Based Loans at the IDB. Document RE-485-6. Washington, DC: IDB. https://publications.iadb.org/en/ove-annual-report-2015-technical-note-design-and-use-policy-based-loans-id

To determine to what extent PBL-supported policy conditions had sufficient depth to trigger long-lasting policy and institutional changes, OVE’s analysis reviewed the content of each policy condition and assigned one of three categories to it:

- Low-depth. Conditions that would not, by themselves, bring about any meaningful changes. Low-depth conditions are usually process-oriented and often involve the preparation of action plans or strategies and the announcement of intentions.

- Medium-depth. Conditions that can have an immediate but not a lasting impact. These include conditions calling for one-off measures that can be expected to have an immediate and possibly significant effect, but that would need to be followed by other measures for this to be lasting. Submission of draft legislation to Congress, reaching a target or benchmarks, and organizational changes are examples of medium-depth conditions.

- High-depth. Conditions that could, by themselves, trigger long-lasting changes in the institutional or policy environment. Conditions in this category include legislative changes, government decrees, or lower-level actions that complete a critical reform process. High-depth conditions also include measures that require that certain fiduciary measures be taken regularly or permanently, even when legislation is not needed.

This analysis was supplemented by an assessment of the programs’ overall vertical logic and coherence. OVE evaluated the sequencing of the conditions across PBL tranches or across individual loans in a programmatic PBL series by looking at the extent to which the policy conditions included in each tranche of a multitranche PBL, or in each loan of a programmatic PBL series, followed a logical sequence over time by supporting different stages of the reform process cycle (i.e., formulation or design, adoption or approval, implementation, monitoring and evaluation). OVE also assessed the program’s vertical logic: the coherence between conditions and the reform program objectives and expected results. While OVE’s analysis of the depth of policy conditions and their sequencing allowed it to gauge the progress of the reform program supported by PBL, the methodology did not measure IDB’s technical additionality to the reform program or the extent to which the impetus for reforms could be traced to IDB actions.

Most conditions involved policy or regulatory measures, while a small proportion focused on organizational changes at public agencies. OVE found that almost 80% of conditions in the sample supported policy reforms, ranging from the design of a new payment scheme for a social program to the approval of fiscal responsibility legislation. The rest promoted changes in the structure, responsibility chain, and/or institutional capacity of public agencies, such as the creation of a public health unit in the Ministry of Health or the formulation of a code to define the structure and processes for a public agency.

Most conditions were low- or medium-depth; they helped set in motion policy reforms but could not by themselves effect lasting changes. Almost a third of conditions in both the multitranche PBL and the programmatic series reviewed were low-depth, calling for basic one-off measures or simply expressing intentions. For example, a condition would commit a line agency to an independent operational audit of a feeding subsidy or call on an agency to prepare terms of reference for the design of a methodology to analyze the outcomes of a national investment plan. It is questionable whether such measures are in line with IDB’s guidelines, which stipulate that PBL conditions should be essential for the achievement of expected results. Only 15% of the conditions in the sample were high-depth, for example the elimination of government budget support for state-controlled enterprises or the adoption of revised targeting mechanisms for a school feeding program. No major differences in the depth level of conditions were found between multitranche PBL and programmatic PBL series.

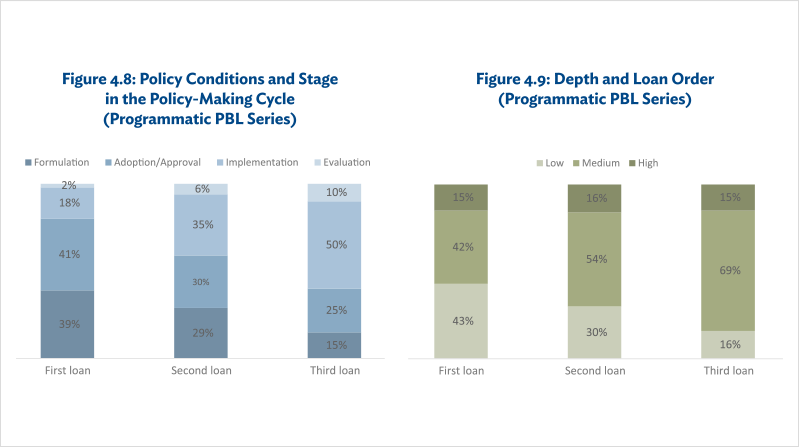

Sequencing of PBL conditions followed the stages of reform cycles and tended to gain in depth as the reform process advanced, but the monitoring and evaluation (M&E) stage was seldom included. OVE classified the conditions in each operation according to the milestones in a policy reform cycle (formulation, adoption, implementation, M&E) that they supported. Not surprisingly, conditions in the first tranche or loan tended to focus on earlier stages of a policy reform process, while a larger proportion of conditions in subsequent tranches or loans tended to focus on implementation (Figure 4.8). Conditions gained in depth as the program advanced. For example, 43% of conditions in the first loans of programmatic PBL series were low-depth, while this proportion decreased to 30% in the second loan and to 16% in the third (Figure 4.9). According to OVE’s analysis, the reviewed conditions were generally relevant to the programs’ objectives, although they were probably insufficient to attain the expected outcomes. Less than 6% of the conditions reviewed included provisions linked to the last stage of a reform process—M&E. Programs in the social sectors were more likely to include M&E conditions, especially when compared with those in the financial sector (0.8% of conditions).

Source: IDB Office of Evaluation and Oversight(OVE). Design and Use of Policy-Based Loans at the IDB. https://publications.iadb.org/en/ove-annual-report-2015-technical-note-design-and-use-policy-based-loans-idb

Programs with a larger number of conditions tended to have a greater share of low-depth conditions. This suggests that IDB could in many cases have been more parsimonious with policy conditions and focused on measures that were critical to achieving the desired results. Similarly, OVE found no correlation between loan amount per capita and how ambitious the reform program was, nor did it find any correlation between loan size and the number of policy conditions. For example, the first loan of a program to strengthen the public finance system in Mexico in the amount of $800 million had 15 policy conditions, while the second loan in support of a water resources reform program in Peru in the amount of $10 million had roughly the same number. These findings are consistent with IDB’s policy-based lending guidelines, which state that the size of the loan is not necessarily related to the cost of the policy reforms or institutional changes supported by the PBL, but rather to development financing requirements.

The depth level of reform programs varied across and within countries; in general, programs in the financial and energy sectors tended to have more depth. When analyzing differences in the depth level, sharp differences across countries were detected. For example, about 22% of the conditions in Peru had high depth, compared with 9% in Colombia programs and less than 5% in Bolivia programs. Moreover, there were substantial differences across programs within countries. In Peru, for example, fewer than 8% of the conditions in a social sector reform program were high-depth conditions, compared with almost 30% in the energy program. The most consistent differences appeared to be at the thematic level: almost a quarter of the conditions in programs in the financial and energy sectors were high-depth, compared with slightly above a tenth in the social and public sector and economic management clusters.

Programmatic PBLs in countries whose reform processes were further advanced at the outset tended to have higher depth conditions. For example, energy sector reforms in Surinam were only modestly advanced when IDB approved a programmatic PBL to help the country develop a framework for the energy sector. Most of the conditions consisted of one-off measures to help set building blocks, such as the preparation of diagnostic assessments and draft guidelines for future legal frameworks. In contrast, a programmatic PBL to support energy sector reforms in Nicaragua supported a reform process that was already advanced and in which the country already had experience. Although it had almost the same number of conditions as Suriname’s, Nicaragua’s PBL had a higher depth level, with conditions that included devising and implementing a new energy tariff structure.

Reforms supported at times of crisis were slightly deeper than those supported outside crisis periods. OVE examined whether PBL programs initiated in times of crisis (which tended to provide countercyclical funding) supported more ambitious reforms than programs started during less adverse economic times. When comparing the depth of the reform programs that were initiated during the global financial crisis (that is, programs for which the first loan was approved during 2008, 2009, or 2010) with those initiated either before or after, OVE found that, on average, programs initiated in times of crisis had slightly higher depth.

- 10For multitranche PBLs, the average number of conditions per loan was found to have increased from 23 to 32.

Complementarity with other Inter-American Development Bank Operations

Over 80% of programmatic PBL series approved between 2005 and 2014 were accompanied by parallel technical cooperation grants. The grants supported policy dialogue, diagnostic work, and compliance with disbursement conditions and averaged $1.3 million per series. While the resources from a PBL go to the country’s Treasury, parallel technical cooperation grants provide direct support for the line ministries in charge of the reforms and can thus help incentivize them to proceed with reform implementation. While PBL programs supported by technical cooperation grants were not found to have deeper conditions than those without such support, OVE found that there was a significant positive relationship between technical cooperation support and the likelihood of a programmatic PBL series being completed, pointing to the importance of sustained dialogue and technical support by IDB to accompany countries’ reform efforts. The presence of technical cooperation grants was neither correlated with a country’s institutional capacity, nor with income per capita. Less frequently (in 15 of the 82 programmatic series), investment loans accompanied programmatic PBL series, with the PBLs either continuing a line of work initiated by previously approved investment loans or preparing the ground for subsequent investment operations.

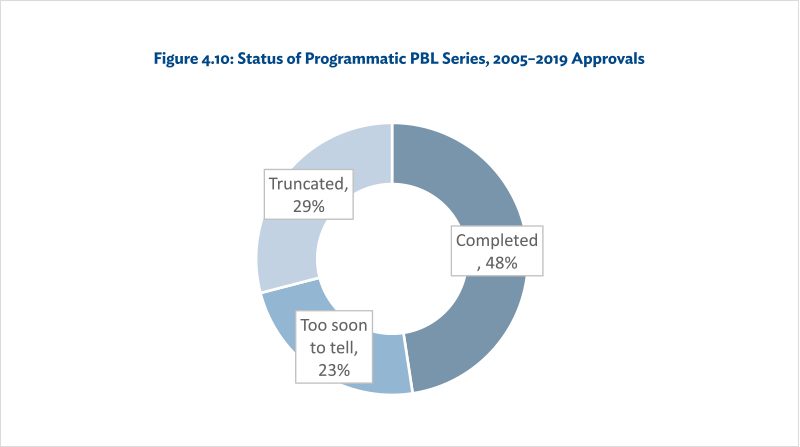

Implementation of Policy-Based Lending

Over one third of programmatic PBL series approved since 2005 have been truncated. OVE’s 2015 review of the design and implementation of PBL operations at IDB found that 32% of active programmatic PBL series between 2005 and 2014 had been interrupted, while 40% had been completed and the remainder were still active, resulting in a truncation rate of 44% (truncated series as a share of completed plus truncated series). An OVE update of this analysis to cover PBL programs approved through 2019 showed only marginal improvement in series completion. Of the 124 programs active between 2005 and 2019, 59 have been completed, 36 have been interrupted and 29 are still ongoing (Figure 4.10, Table 4.3), resulting in a truncation rate of 38%. The truncation rate increases with the number of operations in a series: it is 33% for series with two operations, but 43% for series with three or more operations.

There are significant variations in truncations across countries. For example, Colombia had 16 series between 2005 and 2019 and a truncation rate of over 54%, while Peru with a similar number (15) of programs had a truncation rate of 8%. OVE country program evaluations showed that, in countries with high numbers of truncated series (e.g., Colombia and Panama), IDB often engaged in a new series in a different sector after a series has been truncated. Since medium- and high-depth conditions tend to be concentrated in the second and third loans of a series, the truncation of a series impairs the program’s depth. OVE’s 2015 review of the design and use of PBL found that the truncation rate was higher when there was a change in government, yet almost 20% of programs had been started within a year of elections and over 40% had been started within 2 years of elections, raising questions about IDB’s timing of programs.

Table 4.3: Status of Programmatic PBL Series by Program Size, 2005–2019 Approvals

| Number of Planned Operations in Series | Completed | Too Soon to Tell | Truncated | Total |

| 2 | 34 | 22 | 17 | 73 |

| 3 | 24 | 7 | 18 | 49 |

| 4 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| Total | 59 | 29 | 36 | 124 |

Source: IDB Office of Evaluation and Oversight (OVE), based on data from IDB databases.

In a programmatic PBL series the policy matrix of each operation outlines the conditions applicable to the loan in question, as well as indicative conditions (called triggers) for subsequent loans in the program. In its review, OVE compared the actual policy conditions in second and third loans in a sample of 28 programmatic PBL series to the most up-to-date indicative triggers and found that about half of the triggers had changed during implementation, reflecting the flexibility of the programmatic instrument (Table 4.4). In terms of policy and institutional depth, for about 14% of the triggers in the second loans, and 19% in the third loan, the depth was found to have been reduced when the loan was approved. Conversely, the depth of conditions rarely increased.

Table 4.4. Changes to Disbursement Triggers and Policy Conditions in 28 Programmatic PBL Series

| Changes | Loan 2 | Loan 3 |

| Condition unchanged | 54.5% | 33.6% |

| Condition changed but same depth | 13.2% | 21.2% |

| Condition added | 12.9% | 21.2% |

| Depth decreased | 14.1% | 18.6% |

| Depth increased | 5.7% | 5.3% |

| Number of policy conditions | 335 | 120 |

Source: Based on IDB Office of Evaluation and Oversight (OVE). Design and Use of Policy-Based Loans at the IDB. Document RE-485-6. Washington, DC: IDB. https://publications.iadb.org/en/ove-annual-report-2015-technical-note-design-and-use-policy-based-loans-idb

Recent Developments

Requirements pertaining to policy-based lending at IDB have not changed significantly since OVE’s 2015 review. The main change since the review was a temporary increase in the PBL lending cap from 30% to 40% of overall sovereign-guaranteed lending to accommodate higher demand for budget support in response to the COVID-19 crisis. Before then, IDB introduced loans based on results (LBR) as a new modality under its investment lending instruments in 2016. Under LBRs, the disbursement of funds is linked to the achievement of predefined results rather than against incurred expenditures. LBRs have been used in only six countries and they accounted for only 1% of sovereign-guaranteed lending between 2016–2019. Given the limited experience of the modality thus far, no evaluation of LBRs has been carried out yet.

Conclusions

Policy-based lending was an important IDB instrument during the review period 2005–2019, accounting for about 28% of sovereign-guaranteed approvals and amounting to $42.6 billion. The reasons countries had for using PBL varied, but the predominant use was to help meet financing needs. Policy elements of PBL were usually secondary to the primacy of budget support. This points to a tension between IDB’s dual PBL objectives of supporting borrowing countries’ reforms and helping them meet financing gaps. Many borrowers see PBL primarily as a tool to help meet financing needs.

While OVE’s work found that policy measures supported by PBL were generally relevant to the objectives of the reform programs which they aimed to support, most conditions did not have sufficient depth to set in motion reforms that could by themselves bring lasting changes. Programmatic policy-based loans allow for more sustained engagement and if policy measures become deeper as a programmatic series progresses, they can be a useful tool to support reform programs, while also helping borrowers meet financing needs. However, over one third of programmatic PBL series approved since 2005 were truncated before they reached their most consequential reform steps, raising questions of ownership of the underlying reform programs which such lending sought to support. Truncation was more pronounced for countries that resorted mostly to PBL to meet financing needs and did not seek technical assistance to accompany the underlying reform programs. The fact that programs which were supported by technical cooperation grants had a lower truncation rate indicates there is a need for continuous engagement and technical cooperation to support borrowing countries in their reform efforts. It also suggests that evaluations of PBL should not be undertaken in a vacuum; they need to consider the extent to which the PBL was accompanied by sustained policy dialogue and technical support.

PBL as a financial instrument can either complement or substitute for financing from the financial market. While OVE’s review did not look at this aspect systematically, some of OVE’s country program evaluations show that countries with ample access to financial markets used PBL as a liquidity management tool to complement market financing and fill short-term liquidity needs, particularly outside an economic crisis. While many countries make use of PBL during times of crisis, the countercyclical role which such instruments can play is limited by a cap on overall PBL lending and the limited size of PBL operations compared to the economy in all but small countries.

The findings of OVE’s work undertaken to date invite further questions. To what extent does PBL financing complement or substitute for funding from financial markets? Are IDB-supported policy measures complementary to, or do they overlap with those of other institutions providing budget support? What non-financial additionality does PBL provide? What results have PBL operations helped achieve and how sustainable will those results prove to be? OVE plans to undertake a full-fledged evaluation of policy-based lending at IDB to try to answer some of these questions.

Annex

PBL= policy-based loan, PBP = programmatic policy-based loan, SG = sovereign guaranteed.

Source: IDB Office of Evaluation and Oversight (OVE), based on data from IDB databases.

PBL= policy-based loan, PBP = programmatic policy-based loan, SG = sovereign guaranteed.

Source: IDB Office of Evaluation and Oversight (OVE), based on data from IDB databases.

The Office of Evaluation and Oversight (OVE) at the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) has produced a crisp, candid, and well-structured evaluation of IDB’s policy-based lending (PBL). The report presents many carefully drawn out, relevant, and interesting results. The authors deserve congratulations.

The chapter, which largely reflects the findings of a review of PBL that OVE undertook in 2015, is divided into two sections. The first neatly summarizes facts regarding the evolution of PBL and its use by borrowing countries since its introduction at IDB in 1989. The second assesses PBL along several dimensions (based on well-focused findings), including the reasons why countries demand PBL; complementarities between PBL and other IDB operations; and issues in design and implementation of PBL operations. The chapter provides recommendations for possible amendments to IDB policy-based bending.

The analysis part of the chapter is strong when it comes to findings, but it falls short when interpreting the implications of such findings for IDB and borrowing countries. These comments will therefore elaborate on these and raise a few other questions and issues.

The chapter should from the outset have more frankly recognized that there are potential tensions between the reasons why countries demand PBL, on the one hand, and what multilateral development banks (MDBs) expect to obtain by offering PBL, on the other.

The chapter provides significant evidence that borrowing countries’ use PBL mainly to fill their budget financing needs rather than to intensify high-impact reforms. MDBs do recognize that financing needs are at the heart of the demand for PBL but point to policies and reforms as the main rationale for offering PBL. Reforms are highlighted by MDB staff when justifying a PBL before their Boards of Directors. Efforts to align these two motivations drive PBL preparation and design. These efforts succeed at times, but not always.

It is not surprising that, using a creative analytical approach, the OVE evaluation found that most conditions in PBL were of low- to medium-depth, i.e., they tended to involve one-off and easily reversible policy measures, to be process-oriented, or to contain good policy intentions that are not operationalized for implementation. The OVE evaluation stressed that conditionality in PBL “was generally relevant to the programs’ objectives” yet it clarified that such conditionality “was probably insufficient to attain the expected outcomes.” Or, to put it differently, “most conditions … helped set in motion policy reforms but could not by themselves effect lasting institutional changes.” These findings have important implications, which are discussed below.

Adjusting Multilateral Development Bank Expectations for Policy-Based Lending

The findings of the OVE report should lead MDBs to adjust expectations downward, toward more realistic levels. PBL operations do not simply “buy” reforms, as is often believed. At best, PBL provides needed budgetary financing while recognizing (and helping fine-tune and strengthen the technical aspects of) reforms that would have been attempted by the country with or without the PBL. At worst, PBL operations over-sell and exaggerate the importance and depth of the conditions (reforms) on which they are based.

Nevertheless, the rise in policy-based program loans (PBPs) can be interpreted as a major step towards greater realism and frankness in policy-based lending. PBPs have accounted for the lion’s share of IDB-originated PBL since 2005 (see Figure 2.2 in the IDB OVE’s chapter). Wisely, PBPs do not pretend to “buy reforms.” Instead, they move away from “conditionality” in that each single-tranche loan in the program recognizes and gives credit to the country for policy actions and reforms that have already happened. Future reforms appear only as indicative guides for future tranches under the multi-year program but do not condition the big upfront disbursement associated with the single-tranche in question.

As a result, PBPs address the tricky question of “ownership” (a key issue that is not discussed in the chapter but should have been) while avoiding the time inconsistency trap of traditional PBL operations, where countries under duress agree to conditions (reforms) that have a low probability of being met (because the incentives to stick to the conditions diminish after the PBL is approved and the first disbursement comes in). However, PBPs can lead to marginal or low-depth reforms, cooked up in a hurry by country authorities under the stress of large financing needs, and thus are quite vulnerable to being truncated after the first single-tranche loan has been disbursed. The OVE evaluation found that 38% of PBPs approved since 2005 had been interrupted, with a higher incidence of truncations where loans are approved during times of changes of government.

Related to the question of ownership is the crucial question of whether PBL or PBPs can realistically be expected to generate policy additionality. Given the difficulties in identifying a counterfactual, it is difficult to attribute policy reforms to PBL or, equivalently, to reject the hypothesis that those policy reforms would have taken place even in the absence of PBL. This calls for modesty on the part of MDBs, whose role is not so much to tell countries what to do, but to partner with countries in their quest for social and economic progress, which includes partnering in the process of reform design, implementation, and evaluation. In any case, the chapter should have discussed more fully whether, how, and to what extent PBL promotes country ownership of reforms. This is crucial to avoid situations where a country engages in reforms without conviction but only to get the loan. The chapter should have tried to tease out from the data the counterfactual of whether reforms would have been adopted in the absence of PBL.

In any case, to mitigate the mentioned downsides (low-depth reforms and truncation) of PBPs, a premium must be put on a continued and robust technical engagement and policy dialogue between the MDB and the client country. This is particularly important considering a number of important findings in the OVE evaluation, including that: (i) “IDB tends to support policy reforms in sectors in which it had previously worked (usually through technical cooperation grants and investment loans) and thus has some country-level expertise that allows it to sustain a policy dialogue and provide relevant technical advice;” and (ii) “there was a significant positive relationship between technical cooperation support and the likelihood of a PBP series being completed.”

In other words, the reform impact and non-truncation of PBPs hinge directly on the quality of the policy dialogue that an MDB maintains with client countries and the quality of knowledge services the MDB provides. This is a point that is insufficiently highlighted in the chapter.

This point also argues in favor of not evaluating PBL (or any particular financial product offered by an MDB) in isolation, but in context, i.e., taking into account the entire portfolio of services the MDB offers to its client countries (including financial services, knowledge services, and convening services). The chapter could have been enhanced by relying on such a more contextualized or portfolio approach to the analysis of PBL. In the end, evaluating PBL in isolation may lead to biases in the assessment of MDB value added to development. It should be rather argued that the whole of an MDB engagement in a country (via a portfolio of financial services, technical assistance services, policy dialogue, and convening services) is likely to be larger than the sum of its parts.

PBL and Market-Based Finance

The findings in the chapter raise questions about the complementarity and substitutability of PBL and market-based finance. This is an issue that the chapter does not address but should have. One hypothesis is that, in countries with strong macro-financial policy frameworks, PBL is complementary to market-based finance—that is, these countries use PBL as part of their prudent management of the portfolio of public sector liabilities. In countries with weaker macro-financial policy frameworks, the hypothesis would imply that PBL is a substitute to market-based finance—that is, these countries resort to PBL because they do not have access to market-based finance. The chapter should have explored this hypothesis and elaborated on the implications of what it finds in this regard.

Limits to the Countercyclical Role of Policy-Based Lending

The findings in the chapter invite a richer discussion of the limits to the countercyclical and systemic liquidity functions of PBL. The chapter finds a mild countercyclical pattern: PBL has been negatively correlated with GDP growth. However, it quickly clarifies that “the instrument’s ability to affect macroeconomic conditions in these countries was limited by the small size of the loans in relation to their overall economies.” The leverage limits faced by MDBs (and the associated need for MDBs to retain their high ratings) lead to caps on lending to individual countries. Hence, the chapter should have more frankly recognized that MDBs are not set up to act as international lenders of last resort. That is a function left to the International Monetary Fund (IMF). This should dampen down the wrong, yet widely held, expectation that MDBs can be major players in countercyclical lending and emergency (systemic) liquidity assistance.

The limits to countercyclical lending by MBDs do not, of course, invalidate the prescription (which the evaluation should have highlighted) that MDBs must avoid unduly procyclical lending. In other words, MDBs need to avoid the tendency to join markets in lending copiously and euphorically in good times, which is necessary for MDBs to keep firepower available to provide considerable budget support (via PBL) in bad times. At the same time, the fact that bad times can facilitate a push to reform may play in favor of MDBs in times of crises, even if their countercyclical impact is limited.

The chapter notes the intriguing fact that, starting around 2005, IDB policy-based lending ceased to formally depend on the IMF’s assessment of a country’s macroeconomic viability and can now rely solely on the views of IDB’s own Independent Macroeconomic Assessment Unit within the Research Department. This move is interesting considering that the World Bank tried a similar route but then abandoned it, after a bad experience in Argentina. Have there been specific situations of tension in IDB PBL operations, where the Research Department’s assessment of macroeconomic viability was at odds with that of the IMF? If so, how were those tensions managed? In any case, strengthening an MDB’s capacity to conduct systematic macroeconomic viability assessments—independently or in coordination with the IMF—is particularly relevant given the coronavirus disease (COVID)-induced surge in debt across the world.

Given the need for MDBs to cooperate with the IMF, especially in large, emergency financing packages, the chapter should also have examined the extent to which the policy reforms featured in PBL are incorporated as structural benchmarks in IMF-supported programs.

The chapter should have shown not only PBL disbursements (flows), but also PBL stocks. This would have helped shed light on the relevant question of whether much of the PBL activity is essentially refinancing (disbursements that compensate for amortizations falling due) rather than increases in exposure. In fact, one wonders why MDBs tend to focus so much on disbursement flows and to pay little attention to exposure (stocks). This question deserved at least a footnote in the chapter.

Do burden-sharing and bailing-in considerations play any role in PBL? I assume that IDB is not indifferent to situations where its loans are used by a country mainly to pay (or bail out) private or bilateral external creditors in times of sudden stops or reversals in capital flows. Are there any IDB policy guidelines in this respect? If not, shouldn’t such guidelines be developed?

The fact that budget financing needs, rather than balance of payments needs, are the dominant driver of PBL demand deserves further assessment. This seems to invalidate the traditional view of MDB lending as a means to close a country’s external financing gap. The chapter should have offered a well thought out discussion of why the external financing motive for MDB lending seems to have vanished, at least in normal times. A likely answer would point in the direction of the rising international financial integration of emerging economies.