Methodologies for Evaluating Policy-Based Lending Operations

A comparative analysis of the main methodologies

MARK SUNDBERG

MARK SUNDBERG

MARK SUNDBERG

MARK SUNDBERG

This annex describes the two principal and distinct methodologies used for evaluating policy-based operations (PBOs). Understanding evaluation methods is important for interpreting and using evaluation results. The annex draws on pedagogical materials prepared by the Independent Evaluation Group (IEG) of the World Bank, which is representative of MDB practice, and by the European Commission.

Evaluation of PBOs poses challenges to evaluators beyond those commonly found in conventional investment project financing (IPF), such as infrastructure investments. First, IPF typically lends itself to greater clarity of measurement metrics and greater availability of data. Measurement of physical project outputs (e.g., kilometers of roads built) and intermediate outcomes (e.g., lower transport costs, time savings) have readily quantified metrics that can directly relate to project inputs. Policy-based lending, in contrast, involves work with building national or subnational capacity, legal and regulatory frameworks, and quality of institutions and policies for which metrics are not well established and are difficult to standardize across sectors and countries, often relying on institutional specialists. Second, IPF is normally tied to specific expenditures with fiduciary requirements that include evidence to validate project-linked expenditures in accord with the procurement standards of international financial institutions. PBOs dispense with these specific fiduciary requirements and use partner countries’ own fiduciary and budget management practices.

This raises a third issue, fungibility. All foreign assistance may ease the budget constraint and allow funding to activities other than the donor’s intent. However, the problem of attribution (the counterfactual) is arguably more difficult to address for PBOs, particularly in the context of country partnerships. Results can only be considered a contribution to what the country achieved, which is difficult to evidence and quantify.

Finally, policies and institutions are also contextual and inherently differ across regions and countries as does the interpretation of practices that build on different policy conventions, for example between Anglophone and Francophone accounting practices. Donors cofinancing PBOs often largely agree on what policy and institutional functionality looks like, for example, on good budget management practices that lie behind international Public Expenditure and Financial Accountability (PEFA) ratings. However, donors also often disagree on priority reforms in support packages, specific policy objectives, or on the appropriate measurement of results.1Discussion of these issues with reference to public financial management is found in Matt Andrews et al. 2014.This can add further complexity to evaluating outcomes across multiple donors.

Two main methodological approaches have been used by the MDBs to evaluate PBO program performance: (a) An objectives-based method (OBM) used by most of the MDBs, including the African Development Bank, Asian Development Bank, Caribbean Development Bank, Inter-American Development Bank, and the World Bank k; and (a) the OECD-DAC “three-step approach,”2Methodological details of three-step Approach are presented in OECD (2012). which employs three distinct steps to selectively attribute country outcomes and impacts to budget support and its induced outputs.

The design of the OBM is similar manner to evaluation of investment project operations, focusing on evaluation of the specific program objectives of individual PBOs or a series of PBOs, as stated and formalized in the legal documents of the program. Evaluators using OBM examine the institutions and measures proposed and implemented under the program and weigh the robustness of evidence as to specific country outcomes identified in the operation as reflected in the theory of change. This approach is built around qualitative and quantitative evidence on the outputs and outcomes delivered as a result of specified actions or interventions at a granular level. Based on the evidence available, the evaluator ranks performance using an established scale at the intervention, program, and instrumental levels.

The OECD-DAC’s three-step approach used by the EU works at an aggregated level taking total budget support received by a country to the extent possible, from all development partners providing budget support, and typically covering a decade of support. The first step aims to assess the effects of combined budget support on policies, services, and induced outputs. The second aims to assess social and economic outcomes that have been the target of these public policies and induced outputs. The third step relates the results of the causal analysis of step two to the links established in step one between budget support inputs and the related policy changes to infer the contribution of budget support.

PBO support presupposes that the recipient government has the necessary policy, capacity, incentives, and implementation tools to enforce agreed reforms with desired results. Importantly, it should also have in place a stability-oriented macroeconomic policy framework and fiduciary environment necessary for sustained success. The criteria for this are not detailed, leaving room for institutional judgment and potential departure from IMF macroeconomic assessments and reporting. Policy could be strengthened through the provision of technical support included in (or complementary to) the PBO package. Therefore, country systems, including the use of the general treasury account through which PBO is channeled, are evaluated by the donor ex ante, and must be considered adequate before support is extended. Where country systems are considered weak, programs typically include reform objectives aimed at strengthening public financial management practices. PBO resources are processed through the recipient country’s own financial accounting and budget systems, thus aligning with the Paris, Accra, and Busan principles on aid effectiveness regarding country ownership, donor alignment, donor harmonization, managing for results, and mutual accountability.3See https://www.oecd.org/dac/effectiveness/45827300.pdf.

The intended objectives of PBOs, whether from the EU or MDBs, are essentially the same. In general, PBO is intended to support the recipient government’s implementation of their overall growth and poverty reduction strategy. This generally entails the following:

The theory of change to support these outcomes is based on several assumptions. Budgetary funds are not earmarked, and funds are assumed to help create needed financial opportunities, support greater fiscal flexibility, and enhance incentives because they are not earmarked—notably the amount of financing is not related to any specified costs of reform objectives. Second, it assumes that policy dialogue provides a sharper and shared focus on development outcomes. Dialogue may help to articulate and compare various policy options and identify specific inputs to respond to the implementation needs. Third, it is a source of external discipline exercised through policy conditionality, both ex ante and ex post. A fourth assumption is that capacity development support and related measures fill the capacity gap prioritized by both the donor and country. Finally, the three inputs provided in most PBOs (funding, policy dialogue, and capacity development) are assumed to reinforce each other alongside contextual factors and other government and nongovernment interventions.

The theory of change is based on an intervention logic depicting how budget support inputs help enhance the implementation of the supported development strategies to achieve established targets. However, there are no detailed assumptions on how the inputs provided should be specifically deployed. This is particularly important during economic crises when quick-disbursing and untied financing is critical.

The OBM most MDBs use arose from the need to evaluate individual projects in accordance with the commitment to validate all programs and projects (a practice most MDBs continue to follow). The MDB normally prepares a self-evaluation (a “completion report”) at the close of every operation or program series, following standardized guidelines on methodology and scope.5World Bank (2014b).These reports are intended to provide a complete account of the performance and results of each operation, drawing on evidence collected during and after project completion. The reports assess the extent to which the projects or programs achieve their stated and documented objectives efficiently stating it as an outcome rating of project performance. They also rate the risk to development outcome, the MDB’s own performance, and the borrower’s performance, and the quality of program monitoring and evaluation (M&E).

The next stage of project evaluation is the independent validation of the MDB self-evaluation. The independent evaluation offices of the MDBs conduct these validations on the full agency portfolio. They are desk exercises that rely on the data and coverage in the completion report, but provide a critical review of the evidence, results, and ratings provided in relation to the operation’s design documents. The independent evaluation offices thus arrive at independent ratings for the project based on the same evaluation criteria used for the completion reports.

For a purposeful sample of operations, in-depth evaluations of projects (Project Performance Reports at the World Bank), are also undertaken. These draw on additional evidence and instruments, including field visits to collect administrative data, surveys, and structured and unstructured stakeholder interviews, among other information. The purpose of these evaluations is to gain deeper insight into project performance and what works or does not work at the project level, serving both accountability and learning functions.

The validation reports and project performance evaluations employ the same objectives-based approach to assessing project performance. All elements of evaluation are related to formalized project objectives. As part of assessment and rating of project outcome, the method assesses the relevance of objectives and design as well as the achievement of each objective through the prism of target outcome indicators.

Each evaluation criterion has a specific definition and rating scale for each evaluation criterion as follows:

Outcome: The extent to which the operation’s major relevant objectives were achieved, or are expected to be achieved, efficiently. The rating has three dimensions: relevance, efficacy, and efficiency. Relevance includes relevance of objectives and relevance of design. Relevance of objectives is the extent to which the project’s objectives are consistent with the country’s current development priorities and with current World Bank country and sectoral assistance strategies and corporate goals (typically as these are expressed in national Poverty Reduction Strategy Papers (or country equivalents), Country Assistance Strategies, sector strategy papers, and operational policies). Relevance of design is the extent to which the project’s design is consistent with the stated objectives. Efficacy is the extent to which the project’s objectives were achieved, or are expected to be achieved, taking into account their relative importance. Efficiency is the extent to which the project achieved, or is expected to achieve, a return higher than the opportunity cost of capital and benefits at least cost compared with alternatives. The efficiency dimension is not applied to development policy operations, which provide general budget support. There are six possible ratings for outcome: highly satisfactory, satisfactory, moderately satisfactory, moderately unsatisfactory, unsatisfactory, and highly unsatisfactory.

Risk to development outcome: The risk, at the time of evaluation, that development outcomes (or expected outcomes) will not be maintained (or realized). Possible ratings for risk to development outcome: high, significant, moderate, negligible to low, and not evaluable.

MDB performance: The extent to which services provided by the MDB ensured quality at entry of the operation and supported effective implementation through appropriate supervision (including ensuring adequate transition arrangements for regular operation of supported activities after loan or credit closing toward the achievement of development outcomes). The rating has two dimensions: quality at entry and quality of supervision. Possible ratings for MDB performance: highly satisfactory, satisfactory, moderately satisfactory, moderately unsatisfactory, unsatisfactory, and highly unsatisfactory.

Borrower performance: The extent to which the borrower (including the government and implementing agency or agencies) ensured quality of preparation and implementation and complied with covenants and agreements toward the achievement of development outcomes. The rating has two dimensions: government performance and implementing agency(ies) performance. Possible ratings for borrower performance: highly satisfactory, satisfactory, moderately satisfactory, moderately unsatisfactory, unsatisfactory, and highly unsatisfactory.

These evaluation criteria are assessed for each program objective as identified in the program’s legal documentation. The mix of quantitative and qualitative data sources used for each evaluation varies by sector, country, capacity, and resources available for the evaluation.

An Example of Both Methodologies in Practice: Budget Support to Uganda, 2004–13

In 2015, the European Commission (EC) and IEG undertook the first joint evaluation of all donor budget support to Uganda for 2004–13 (European Commission and Independent Evaluation Group 2015). The EC and the World Bank, the two largest donors, closely coordinated budget support with other bilateral donors through a budget support coordinating group. This major evaluation covered multiple sectors, including cross-cutting themes of macroeconomic and fiscal management, governance and accountability, public financial management, and gender, as well as special sector focus on education, health, and water and sanitation. It was based on intensive document analysis and fieldwork, including visits to secondary towns, stakeholder and service provider surveys, and statistical analysis. The evaluation used the standard OECD-DAC EC evaluation methodology for evaluating budget support operations.6Caputo, Lawson, and van der Linde 2008.

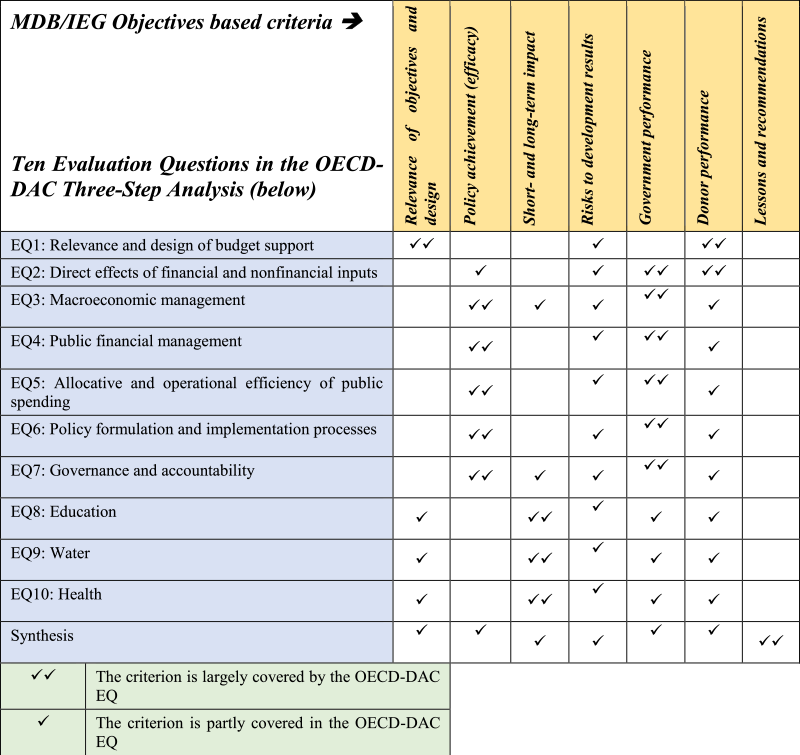

Table A.1: Cross-Linkages between the Third Step of the OECD-DAC Approach (first column) and MDB Objectives-Based Approach (top row)

Source: World Bank and European Commission 2015, Volume 1. Additional two dimensions (not shown in the table for clarity reasons) are elements of both the IEG and EC-DAC methodologies: monitoring and evaluation and "unintended effects."

In parallel the World Bank team prepared its own evaluation, following the objectives-based methodology, of the World Bank’s two series of budget support operations to Uganda, which were approved and closed during the period 2006–13 (IEG 2015b). The overarching objective of the first series was to support the implementation of the government’s third Poverty Eradication Action Plan (PEAP). The two objectives of the second series were improved access to, and greater value for money in, public services. These programs comprised a significant share of the overall, closely coordinated, EC-World Bank budget support. This allowed comparison of the performance of the World Bank across two periods and two budget support series. The first series was found to be less successful, and the second more successful, due in part to learning from the design problems with the first series.

The joint evaluation exercise using the two methodologies offers an opportunity to compare and contrast the two methods. Table A.1 illustrates the analytical framework combined the Evaluative Questions-based approach of the OECD-DAC methodological guidelines to evaluate budget support and the objective-based approach of MDB/IEG for strategic evaluation. The table highlights the proximate relations between the two approaches in various elements of the evaluation. The first column lists the 10 evaluation questions, which are tailored to the specific country context and operation and are addressed covering all budget support operations during the evaluation period. The seven columns across the top list the evaluation criteria used by the OBM approach of the World Bank. Each cell indicates how closely these overlap between the two (largely, partly, or not at all). For example, column 1 shows that the OBM focus on “Relevance of objectives and design” is picked up in the OECD-DAC evaluation question 1, and partially reflected in the three sector evaluation questions plus the synthesis.

Three conclusions stand out from a comparison of evaluation coverage and scope in the two approaches. First, the MDB/IEG assessment is objectives-based and includes performance ratings. It follows standard, preset evaluation criteria for all such assessments: relevance, efficacy, impact, risks, government and World Bank performance, and lessons and operations. The explicit ratings cover the various dimensions of assessments, including the overall rating for the budget support series, on a six-point scale from highly unsatisfactory to highly satisfactory. As such, the MDB/IEG approach is especially suited for assessing accountability of individual operations or groups of operations in a given country. It also offers an opportunity to reflect on broader lessons and provide recommendations for improvements in future operations.

Second, the OECD-DAC approach does not have preset evaluative questions, although it follows a clear, three-step analytical framework described in the next section. Evaluative questions vary from assessment to assessment depending on the focus of the EC budget support and the interest in specific questions to be answered by the EC donors. Importantly, the EC approach does not have ratings. As such, it is geared more toward learning lessons. It also has an element of accountability assessment with regular reporting, despite the lack of explicit ratings.

Third, these differences suggest that the MDB/IEG approach, being uniform and explicit about ratings offers an opportunity for quantitative comparisons of evaluations, both cross-operational and cross-country. By contrast, comparisons of EC assessments across operations are typically focused on total country budget support and are not based on ratings. This lends itself to more qualitative and country-oriented lessons than quantitative comparisons.

It should be acknowledged that in both methodologies there is considerable need for evaluator judgement as to the quality and weight of the evidence. More robust, quantitative methods and development of the counterfactual to permit attribution by donor or instrument are generally not possible.

The OECD-DAC results-based method follows a three-step analytical framework aimed at discovering how the opportunities provided have been used to develop the policy process to achieve outcomes.7This section draws principally on OECD-DAC (2012) and on Bogetić, Caputo, and Sundberg (2018). It also aims to develop a narrative regarding how, and through which dynamics, targeted development outcomes have evolved. The three-step process logically focuses on (a) policy processes, (b) development outcomes and causal factors, and (c) a synthesis narrative of a and b aiming to identify contributing factors and broader lessons. To ascertain how and to what extent the opportunities provided by budget support have been used to strengthen government policies toward the achievement of the agreed results, the evaluation uses a contribution analysis 8Contribution analysis is the standard method of choice where experimental or semi-experimental approaches are not applicable, especially in cases addressing complex evaluations with multiple interactions. This method has been discussed since the mid-1990s. One of its earliest and most convincing definitions is that of Hendricks (1996), who states that the contribution analysis aims at identifying “plausible associations” between a program and the targeted development outcomes. John Mayne’s approach to contribution analysis has been discussed and adopted by various institutions, including the World Bank (IEG), the IMF, and others (World Bank 2014; Dwyer 2007). Using contribution analysis, the evaluator does not expect to rigorously measure and quantify the exact level of the program’s contribution to the targeted outcomes. Rather, it aims at building a robust story and factual and data evidence on how and to what extent the program has contributed to the achievement of the targeted outcomes.divided into two steps (step 1 and step 2) and then synthesized in step 3. Through the evidence collected, contribution analysis aims to build a body of relevant evidence and a credible story on the relationships between budget support inputs and targeted development outcomes, mediated through government policies.

In step 1, the approach aims to investigate whether the resources provided by budget support are used by the government to strengthen its development policy and institutional process in the given context (relevance). The government may be engaged in different priorities from those stated in the strategies. Country-level and general lessons may be drawn on the negotiation and design processes. Second, it investigates to what extent and how the government has used the capacities and opportunities provided by budget support to strengthen its own policy and institutional processes (efficiency and effectiveness).

In step 2, the focus is on development outcomes in the broader national context, beyond external assistance and PBF/budget support (i.e., what happened during the period under review). A statistical analysis identifies changes in development outcomes and impacts and a regression analysis captures their explanatory factors, not limited to but including policy measures. The causal analysis thus identifies the policy and institutional changes that have contributed to the achievement or nonachievement of observed results.

In step 3, the assessments carried out in steps 1 and 2 are synthesized and compared, thereby enabling the establishment of contribution links between budget support and development outcomes, through the government policies, the latter being at the same time partly influenced by budget support inputs and opportunities and partly responsible for the achievement of the targeted outcomes. Step 3 provides a narrative of budget support contributions to development change in a given country context.

The evaluation must build a credible story that accounts for specific, different features in each country, so it must uncover how these key causal links materialize (the specific mechanisms). The assessments to be carried out to build the evaluation story are different in step 1 and step 2. In the first case, the facts to be analyzed and the actors to be considered are usually accessible and close to the budget support inputs, and the relationships and links to be assessed are rather direct. In step 2, identification of the policy processes that lead to the results is underpinned by statistical analysis and/or historical methods. Finally, guided by the theory, the evaluator synthesizes the application of these assessment criteria, identifying the contributions of budget support inputs to policy (induced) outcomes.

Based on the theory of change, the formulation of the evaluative questions (EQs) must contain the various hypotheses and indicators necessary to understand how the government has used the resources provided and how the dialogue has or has not allowed facilitation of a constructive use of such resources. Instead of verifying a predefined sequence of causal links, as happens in a project evaluation, the EQs must help identify the broader context within which the cluster of budget support operations takes place, the opportunities created or missed, and how the different parties have used them. The EQs address the various levels of the intervention logic. The first set of EQs (step 1) compare planned budget support inputs and those provided (relevance, size, predictability, coordination with technical assistance, alignment with external support, and others) and the improvements in areas that are being supported. Step 2 EQs assess expected achievements in terms of development results at outcome and impact level as defined in the budget support agreements. Finally, the step 3 EQs turn to addressing the extent, and mechanisms through which, budget support contributed to the attainment of development results identified in step 2.

The three-step methodology was deployed several times before being adopted by the OECD-DAC Network on development evaluation in 2012. In 2014 the EU commissioned a synthesis of seven evaluations undertaken since 2010. The synthesis looked at the strengths and weaknesses of the three-step approach, among other things. The specific tools and evaluation techniques used by each evaluation team were compared and assessed to develop recommendations on possible improvements to evaluation practices. These covered methodological, managerial, and process issues.

To improve the methodological approach, the study recommended that (a) a contextual analysis be introduced systematically in each evaluation; (b) step 2 analysis considers the possibility of reliance on secondary rather than primary data analysis and/or more qualitative approaches (such as benefit-incidence surveys or perception surveys); (c) development partners management response to evaluation recommendations be strengthened; (d) evaluation reporting formats be simplified; (e) the classification and presentation of evidence collected be simplified so as to facilitate comparability across evaluations; and (f) that the evaluation approach could become an integral part of the domestic policy processes if it is led by the country rather than the donors. These recommendations were taken into account in the budget support evaluations that have followed, but the methodology has not changed since its adoption.

Regarding the MDB/IEG approach, some proposed changes to practice being rolled out by IEG are discussed by Bogetić and Chelsky in chapter 6 of this volume. In summary, they highlight the need for greater recognition of PBO as a different aid instrument from traditional project finance, and emphasize the critical role played by the identification and selection of conditionality (prior actions), which are necessary conditions for Board approval of PBO loans by the World Bank. They argue that prior actions are key reform elements but have not received sufficient attention in past evaluations. Finally, they note some recommended changes to practice: (a) eliminate evaluation of the borrower’s performance but retain evaluation of MDB performance; (b) streamline and reduce the number of ratings; (c) increase use of machine learning tools that automatically or semi-automatically help increase the efficiency of organizing and analyzing large amounts of quantitative and qualitative data.

Andrews, Matt, Marco Cangiano, Neil Cole, Paolo de Renzio, Philipp Krause, and Renaud Seligmann. 2014. “This is PFM,” CID Working Paper, No. 285 July 2014, Cambridge MA.

Bogetić, Željko, Enzo Caputo, and Mark Sundberg. 2018. A Methodological Comparison of the OECD-DAC EC and the IEG Approaches and Some Lessons. Paper presented at the European Evaluation Society (EES) Meetings, Thessaloniki, Greece, October 1–5, 2018.

Caputo, Enzo, Andrew Lawson, and Martin van der Linde. 2008. Methodology for Evaluations of Budget Support Operations at Country Level, Issue Paper, the European Commission.

Dwyer, Rocky J. 2007. “Utilizing simple rules to enhance performance measurement competitiveness and accountability growth”, Business Strategy Series, 8 (1): 72-77.

Hendricks, M. 1996. “Performance Monitoring: How to Measure Effectively the Results of our Efforts.” Paper presented at the American Evaluation Association Annual Conference, Atlanta, GA, November 6.

Independent Evaluation Group. 2015a. Quality of Macro-Fiscal Frameworks in Development Policy Operations. World Bank. Washington, DC.

Independent Evaluation Group (IEG). 2015b. Project Performance Assessment Report of the PRSC5-7 and PRSC8-9. Report No. 96202. June 22.

Lawson, Andrew. 2015. “Review of Methodological Issues Emerging from 7 Country Evaluations of Budget Support.” Study carried out on behalf of the European Union EC-DEVCO.

Maxwell, Joseph A. 2004. “Using Qualitative Research for Causal Explanations,” Field Methods, 16 (3), 2004, Sage Publishing.

OECD-DAC. 2012. Evaluating Budget Support: A Methodological Approach. OECD. Paris.

World Bank. 2014a. “Financial Inclusion—A Foothold on the Ladder Toward Prosperity? An IEG Evaluation of World Bank Group Support for Financial Inclusion for Low-Income Households and Microenterprises.” Approach Paper 93624, World Bank, Washington, DC. (See, in particular, box 6 on contribution analysis).

World Bank. 2014b. “Guidelines for Reviewing World Bank Implementation Completion and Results Reports: A Manual for Evaluators,” Independent Evaluation Group, August 2014, World Bank, Washington, DC.

World Bank. 2015. “Quality of Macro-Fiscal Frameworks in Development Policy Operations.” IEG Learning Product 97628, World Bank, Washington, DC.

World Bank and European Commission. 2015. Joint Evaluation of Budget Support to Uganda: Final Report. Washington, DC: World Bank.