International financial institutions use different names for policy-based financing (PBF) or policy-based operations/lending (PBOs/PBLs), which refers to budget support to help promote the recipient governments’ policy and institutional reforms. The World Bank generally refers to this as development policy financing (DPF), delivered through different varieties of DPF instrument depending on the nature of the financing provided. A development policy loan is a common type. If the financing is in the form of a grant (typically provided to low-income country recipients from the World Bank Group’s International Development Association [IDA] resources), the PBF will usually take the form of a development policy grant.

Financial support through DPF can also take the form of a guarantee, for which a policy-based guarantee (PBG) is used,1With a PBG, instead of providing financing directly to the client, the World Bank provides a guarantee for a portion of the principal and/or interest on the loan while commercial creditors provide the loan itself via direct commercial lending or via client government international bond issuance.or as contingent financing, depending on the activation of an indicative trigger related to natural disasters or health crises (for example, a DPF with a deferred drawdown option). Other varieties of the DPF instrument have been used over time—for example, poverty reduction support credits (PRSCs)—but are no longer used. DPF can be provided through a single, stand-alone operation or through a programmatic series of operations, linked by indicative policy triggers. DPF is provided to sovereign national governments of World Bank member states and, sometimes, to subnational governments.

- 1With a PBG, instead of providing financing directly to the client, the World Bank provides a guarantee for a portion of the principal and/or interest on the loan while commercial creditors provide the loan itself via direct commercial lending or via client government international bond issuance.

Historical Development and Use of Policy-Based Financing, 2005–2019

The World Bank’s policy on DPF states: “a DPF is aimed at helping a Member Country address actual or anticipated development financing requirements that have domestic or external origins. The [World] Bank may provide a Bank Loan to a Member Country or to one of its Political Subdivisions; and it may provide a Bank Guarantee of debt incurred by a Member Country or by one of its Political Subdivisions.”2World Bank. 2017. The World Bank Operational Manual: Operations Policy OP/BP 8.60. Washington, DC: World Bank. Section III.DPF aims to help the borrower achieve sustainable poverty reduction through a program of policy and institutional actions, for example, strengthening public financial management, improving the investment climate, addressing bottlenecks to improve service delivery, and diversifying the economy. DPF provides general budget support, meaning that the funds are disbursed into the general budget of the client government and are not tied to specific budget items.

DPF is provided after implementation of a set of policy and institutional actions (prior actions) that support the achievement of development policy objectives, consistent with the recipient’s national goals and strategies and the World Bank’s strategy in the country. Implementation of all prior actions is a condition for approval by the Board of Executive Directors. The purpose of the prior actions is to advance, catalyze, or signal broader reforms and demonstrate credibility and ownership necessary for their success. Well-defined results indicators, with clear baselines and time-bound targets, monitor progress toward objectives. A credible results chain (or theory of change) links objectives, prior actions, other activities, and results indicators. The policy framework is developed through a policy dialogue between the World Bank and the recipient government.

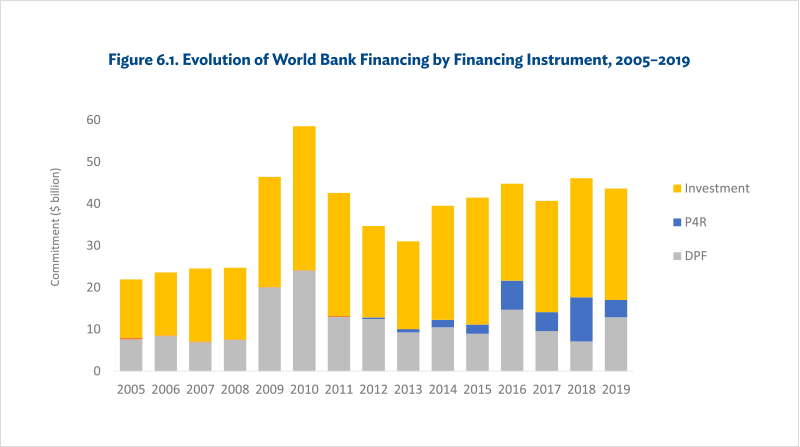

At the World Bank, over the past decade and a half, DPF operations have typically accounted for between one-quarter and one-third of World Bank financing commitments, rising during times of major crises to as high as 40% (Figure 6.1). The use of DPF escalated during the global financial crisis in 2007–2009 because it was used to provide countercyclical financing to many developing country recipients. This has also been the case during regional crises.

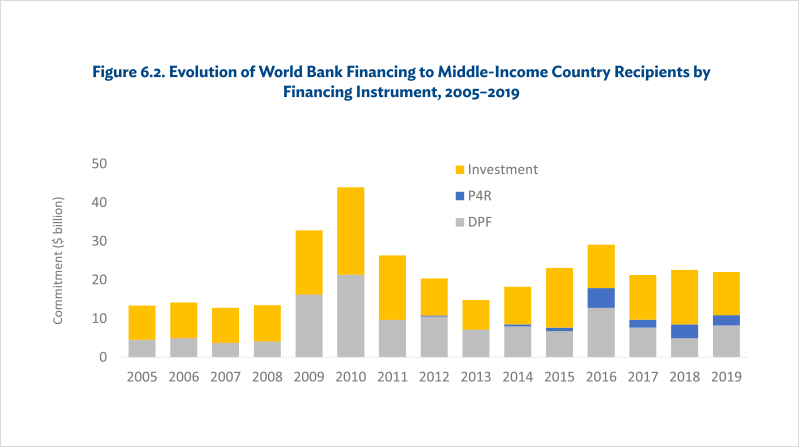

The World Bank has historically made relatively greater use of development policy financing (as part of overall development financing) in middle-income than to low-income countries. To some extent, this reflects the more advanced institutional and absorptive capacities and better developed systems of public expenditure management and budget planning in these countries. The global financial crisis had a disproportionate impact on middle-income countries, and, in response, the World Bank scaled-up DPF operations to middle-income country recipients during and immediately after the crisis (Figure 6.2).

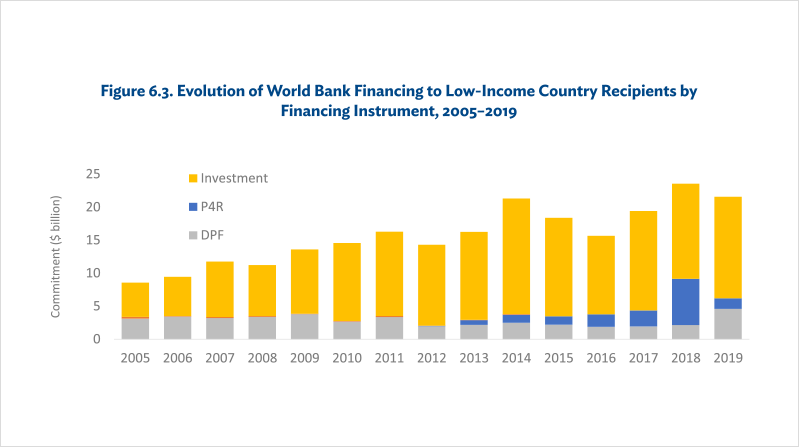

Investment project financing from the World Bank is relatively more important in low-income countries. However, a growing number of low-income countries, especially in Sub-Saharan Africa, and particularly since the onset of the COVID pandemic, are now receiving budget support through DPF (Figure 6.3). The largest low-income country recipients of DPF between 2005 and 2019 were Bangladesh, Ghana, Pakistan, Viet Nam, and Tanzania.

Programmatic development policy operations—a series of consecutive budget support operations in support of a common set of objectives and reforms—have become more common at the World Bank, reflecting their ability to more consistently support longer-term reforms, particularly in the context of a stable policy environment. They enable policy dialogue to continue, reforms to be monitored, and midcourse corrections to be made, as needed. By contrast, stand-alone loans may be more appropriate in the context of either short-term needs or situations of uncertainty (for example, re-engagements, crises, political uncertainty), when the World Bank needs to balance the need to support clients while maintaining flexibility regarding subsequent commitments.

- 2World Bank. 2017. The World Bank Operational Manual: Operations Policy OP/BP 8.60. Washington, DC: World Bank. Section III.

Use of Policy-Based Financing in the World Bank’s Response to the COVID-19 Pandemic

Given the seriousness of the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic and the threat it poses to development gains and future progress, the World Bank has brought its full range of instruments, including DPF, to bear in support of its clients. DPF supports clients in several ways, even when operations are not tagged explicitly as part of a COVID-19 response. DPF provides countercyclical financial support to help countries to maintain critical public services, address rising health care needs, and replace revenues lost from declining economic activity. The prior actions in DPF operations support reforms that will improve the efficiency of public sector spending, thereby making better use of increasingly scarce public resources. This can include improving budget processes to ensure that resources are allocated to the most critical needs, supporting private sector development to help sustain firms during the crisis, and strengthening their eventual recovery (including by encouraging reforms that lower the costs of doing business).

At the outset of the COVID pandemic, the World Bank Group committed itself to providing up to $160 billion, in total financing (IBRD, IDA, IFC, MIGA, and from trust funds), from April 2020 through the end of June 2021 to help countries address the health, social, and economic impacts of COVID-19, while maintaining a line of sight to their long-term development goals. This financing comes from a variety of instruments (including DPF) through new operations and restructuring existing ones to strengthen country capacity to address health, economic, and social shocks. It includes $50 billion in IDA financing for low-income country recipients. The support is organized around four pillars: saving lives, protecting the poor and most vulnerable, ensuring sustainable business growth and job creation, and strengthening policies, institutions, and investments for rebuilding better.3World Bank. 2020. Supporting Countries in Unprecedented Times: Annual Report 2020. Washington, DC: World Bank.By June 2021, the Bank provided $157 billion in overall financing support to client countries, of which $98.9 was accounted for by IBRD financing for middle-income countries and IDA financing for low-income countries.4The World Bank 2021. Annual Report 2021: From Crisis to Green, Resilient and Inclusive Recovery. World Bank. Washington D.C.Of this, about $28 billion was provided in development policy financing for crisis support, $10 billion to middle-income and $8 billion to low-income countries.5World Bank. 2021. 2021 Development Policy Financing Retrospective: Preliminary Findings. OPCS. World Bank: Washington D.C. pp. 24-25. https://thedocs.worldbank.org/en/doc/15a18cacdbcf0b366069d95225036969-0290032021/original/Development-Policy-Financing-DPF-2021-Retrospective-Preliminary-Findings.pdfThis $28 billion in DPF in support of the COVID19 crisis response during April 2020-June 2021 compares with $12.9 billion provided in the FY2019 as shown in Figure 6.1.

- 3World Bank. 2020. Supporting Countries in Unprecedented Times: Annual Report 2020. Washington, DC: World Bank.

- 4The World Bank 2021. Annual Report 2021: From Crisis to Green, Resilient and Inclusive Recovery. World Bank. Washington D.C.

- 5World Bank. 2021. 2021 Development Policy Financing Retrospective: Preliminary Findings. OPCS. World Bank: Washington D.C. pp. 24-25. https://thedocs.worldbank.org/en/doc/15a18cacdbcf0b366069d95225036969-0290032021/original/Development-Policy-Financing-DPF-2021-Retrospective-Preliminary-Findings.pdf

Independent Evaluation Group Evaluation and Validation of Development Policy Financing Operations

At the close of every World Bank DPF operation (or programmatic series of operations), the unit which prepared the operation produces a self-evaluation in the form of an implementation completion and results report (ICR). ICRs are intended to provide a candid and systematic account of the performance and results of each operation or programmatic series of operations, drawing on evidence collected during the life of the project and after completion, thereby contributing to World Bank learning and accountability. The ICR assesses the extent to which operations have achieved their relevant objectives, self-assesses World Bank performance and, until recently, rated borrower performance.

IEG conducts validations of all ICRs. The resulting report, the ICR review (ICRR), is the main operation-level assessment of operational performance. The ICRR validates the ICR’s analysis and findings, providing an independent, desk-based, critical review of the evidence, results, and ratings of World Bank self-evaluation. Based on the evidence provided in the ICR and an interview with the relevant task team leader, IEG arrives at an independent rating for the operation. The ICRR may downgrade the rating of an operation from the staff self-assessment, sometimes because of shortcomings in the evidence in support of achievement. IEG reports aggregated data on the disconnect between staff and IEG ratings to the Board, which provides some degree of discipline on the objectivity of the self-assessment. IEG conducts in-depth evaluations (project performance assessment report) for a subset of operations with a completed ICRR, based on additional evidence (including field visits with extensive interviews of relevant stakeholders) to gain deeper insights into what works and what does not, serving both accountability and learning functions.

ICRs and ICRRs have traditionally taken an objectives-based approach to evaluating performance by assessing the relevance of the objectives and design and the achievement of each objective with reference to targets for pre-identified results indicators. This methodology is similar to the approach used to evaluate and validate investment projects. Recently, the World Bank and IEG reformed the approach to assessing budget support operations to better reflect the characteristics of DPF operations. This new framework, which began being implemented recently, is discussed below in the penultimate section “The Evolving Framework for the Evaluation of World Bank Development Policy Financing.”

Assessments of Relevance

Previously, ICRs and ICRRs discussed and rated the relevance of project development objectives (PDOs) and the design of the operation. They looked at the extent to which an operation’s objectives, design, or implementation were consistent with the country’s current development priorities, current World Bank country and sectoral assistance strategies, and corporate goals. The requirement for consistency (or alignment, as it was often called) did not explicitly require that the operation tackle the most challenging constraints to achieving development objectives (although the accompanying guidance called for the evaluation to take into account “whether the [World] Bank’s implementation assistance was responsive to changing needs and that the operation remained important to achieving country, [World] Bank, and global development objectives”). Indeed, many budget support operations had high-level objectives that were almost always relevant in developing economies (for example, strengthen public finances, promote private sector development, or improve public financial management).

The relevance of PDOs for investment project financing (IPF) tended to be defined more narrowly, considering, among other things, the primary target groups of the project and the change or response expected from this group because of the project’s interventions. Investment projects also tended to focus on outcomes for which the project could reasonably be held accountable. According to the guidelines for IPF self-evaluation, a PDO “neither encompasses higher-level objectives beyond the purview of the project, nor [is it] a restatement of the project’s activities or outputs.”

As a result of their relatively high level, most relevance assessments for DPF objectives and design were quite favorable. Indeed, over the past 5 years, the share of DPF operations with ratings for the relevance of objectives that were “moderately satisfactory” (MS) or better was above 95%.

Assessments of Efficacy

Efficacy for DPF was defined as the extent to which the operation’s objectives were achieved or were expected to be achieved, and the extent to which that achievement is attributable to the activities or actions supported by the operation. In using the operation’s results indicators to assess efficacy, the evaluator implicitly assessed whether these were the right indicators to use to measure achievement of expected outcomes. However, efficacy was often determined largely by assessing the achievement of targets for the operation’s results indicators alone. The efficacy rating was rarely discounted because of results indicators that either did not capture progress toward the objective or that did not reflect the impact of the prior action in question. Consideration of the adequacy of results indicators tended to appear toward the end of the evaluation in the monitoring and evaluation section of the ICRR, after efficacy had been assessed and rated.

Evolution of the Performance of World Bank’s Development Policy Financing Operations

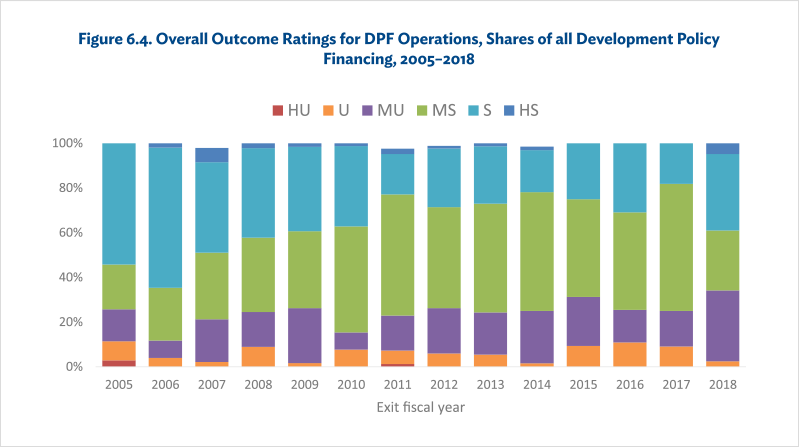

In preparing this chapter, we briefly reviewed data on IEG-validated ratings for DPF operations, focusing on the ratings for overall outcome and World Bank performance. Over the period 2005–18, just over three-quarters of the World Bank’s DPF operations were rated Moderately Satisfactory or higher (MS+) for overall outcome.6The rating for overall outcome is derived from subratings for the relevance of objectives and efficacy (i.e., the achievement of objectives).The MS+ rating is used to track the operational performance of World Bank projects and DPF operations in the World Bank Group’s Corporate Scorecard.7For more information, visit: https://scorecard.worldbank.org/Although this ratio has been relatively stable over the period, there has been a decline in operations rated satisfactory, largely offset by an increase in operations rated moderately satisfactory (Figure 6.4).

- 6The rating for overall outcome is derived from subratings for the relevance of objectives and efficacy (i.e., the achievement of objectives).

- 7For more information, visit: https://scorecard.worldbank.org/

Assessing World Bank Performance in its Development Policy Financing Operations

Between 2005 and 2018, World Bank performance in evaluations of DPF operations was defined as the extent to which services provided by the World Bank ensured quality at entry of the operation and supported effective implementation through appropriate supervision. Quality at entry referred to the extent to which the World Bank identified, facilitated the preparation of, and appraised the operation so it was most likely to achieve its planned development outcomes and was consistent with the World Bank’s fiduciary role. The quality of World Bank supervision was the extent to which the World Bank proactively identified and resolved threats to the achievement of the relevant development outcome and carried out its fiduciary role.

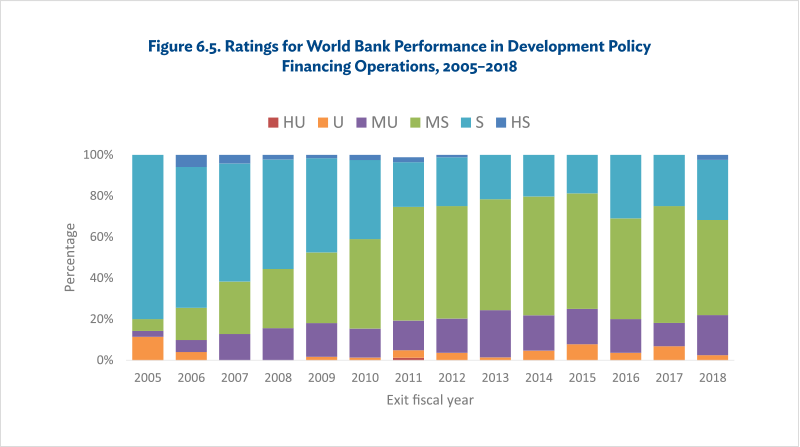

Figure 6.5 illustrates the evolution of ratings of World Bank performance since 2005. The share of operations rated MS+ was relatively stable, averaging about four-fifths of all operations between fiscal years 2005 and 2018. As with overall outcome ratings, there was a deterioration in the share of operations with a satisfactory World Bank performance rating, offset by an increase in the share of operations with World Bank performance rated MS, suggesting a decline in average quality, although that trend has reversed in recent years.

Some Empirical Findings on World Bank Development Policy Financing

Several studies have provided insights into the correlation of outcomes from World Bank DPF operations (as measured by overall outcome ratings from ICRRs) and characteristics of those operations.8For a retrospective overview of Bank’s DPF, see World Bank 2015. World Bank Development Policy Financing Retrospective, Results and Sustainability. World Bank.However, given the complexity of the results chain underpinning most policy reforms, these studies do not establish causality.

Smets and Knack9Lodewijk Smets and Stephen Knack. 2014. World Bank Lending and the Quality of Economic Policy. World Bank Policy Research Paper. No. 6924.explored how the World Bank’s policy-based lending has influenced the quality of economic policy, given the focus of DPF on policy reforms as immediate and intermediate objectives. Their analysis focused on the early part of the broad results chain of aid outlined by Bourguignon and Sundberg,10Francois Bourguignon and Mark Sundberg. 2007. Aid Effectiveness: Opening the Black Box. American Economic Review. Vol. 97, No. 2, pp. 328-21from aid to policy making and policies, but it did not address the subsequent link between policies and country outcomes. To this end, the authors used elements of the World Bank’s Country Policy and Institutional Assessment (CPIA) ratings as the dependent variable and as a proxy for the quality of economic policy. Although past studies found only limited association between DPF operations and the macroeconomic stability component of the CPIA, the authors examined those links and focused specifically on macroeconomic and fiscal issues, in particular macroeconomic stability as measured by the relevant CPIA indexes. They did not find an association between DPF operations and macroeconomic stability. However, they did not address reverse causality, i.e., the possibility that the DPF operation was selected because of stable macroeconomic conditions. This is important because the World Bank requires macroeconomic stability at the time of approval.

Moll, Geli, and Saavedra11Peter Moll, Patricia Geli, and Pablo Saavedra. 2015. Correlates of Success in World Bank Development Policy Lending. World Bank Policy Research Paper. No. 7181.empirically tested whether elements of operations design (for example, prior actions, results frameworks, and task team leader skills and professional affiliation) influenced the success of World Bank DPF, as measured by IEG-validated overall outcomes for 2004–2013. They controlled for income per capita, quality of macroeconomic and governance-related policies, and force majeure as measured by natural disasters. They found that the line of sight between the policy reform supported and the results framework was critical for success, while the skills of the task team leader and a professional affiliation with the Poverty Reduction and Economic Management network of the World Bank was also associated with greater DPF success.

Bogetić and Smets12Željko Bogetić and Lodewijk Smets. 2017. Association of World Bank Policy Lending with Social Development Policies and Institutions. World Bank Policy Research Paper. No. 8263.found that the World Bank’s policy lending was significantly and positively correlated with the quality of social policies and institutions. They also found that loan conditions related to social protection and environmental sustainability were associated with better social policies and institutions more than those related to the equity of public resource use, and with health and education. These findings reinforce the idea that the type and quality of World Bank conditionality matters for the design and outcomes of policy-based lending.

- 8For a retrospective overview of Bank’s DPF, see World Bank 2015. World Bank Development Policy Financing Retrospective, Results and Sustainability. World Bank.

- 9Lodewijk Smets and Stephen Knack. 2014. World Bank Lending and the Quality of Economic Policy. World Bank Policy Research Paper. No. 6924.

- 10Francois Bourguignon and Mark Sundberg. 2007. Aid Effectiveness: Opening the Black Box. American Economic Review. Vol. 97, No. 2, pp. 328-21

- 11Peter Moll, Patricia Geli, and Pablo Saavedra. 2015. Correlates of Success in World Bank Development Policy Lending. World Bank Policy Research Paper. No. 7181.

- 12Željko Bogetić and Lodewijk Smets. 2017. Association of World Bank Policy Lending with Social Development Policies and Institutions. World Bank Policy Research Paper. No. 8263.

Findings on Development Policy Financing Performance from IEG Thematic Evaluations and Learning Products

IEG thematic evaluations and learning products (and the World Bank’s DPF retrospective) provide rich insights into various dimensions of DPF performance, especially with respect to results frameworks, policy-based guarantees, use of DPF as an anti-crisis instrument, macroeconomic frameworks, and the performance of DPF in low-income IDA countries. The findings included the following:

- Results frameworks in DPF documents have improved, but shortcomings remain in the relevance of results indicators and prior actions. In particular, prior actions were found to be lacking in many instances in the sense that their completion did not contribute critically to development objectives.13World Bank. 2015. Quality of Results Frameworks in Development Policy Operations. Washington, DC: World Bank.

- IEG’s review of evidence from the early policy-based guarantees (PBGs) during the 2011–2015 period found that borrowers, with World Bank support, could typically meet their financing needs during difficult market conditions. A robust macroeconomic and fiscal policy framework was essential for sustaining benefits from improved access to private finance for deficit financing. The impact of PBGs on borrowers’ credit terms varied from one program to another, but in all of the PBGs that IEG reviewed, the aggregate interest rates were lower than they would have been without guarantees; however, more evidence is needed on the benefits when the implied interest rate is calculated on nonguaranteed terms and takes account of the erosion of the guarantee’s value over time.14World Bank. 2016. Findings from Evaluations of Policy-Based Guarantees. Washington, DC: World Bank.

- The World Bank responded to the global financial crisis, especially in middle-income countries, with 67 crisis response development policy operations focused largely on anti-crisis fiscal management. Policy frameworks focused on the timely provision of budget financing at the time of market turbulence and measures to strengthen fiscal sustainability by improving the effectiveness of public expenditures. They included improvements in the targeting of social entitlements and cuts in unproductive expenditures. At the same time, and because of their counter-cyclical focus, policy frameworks included comparatively few structural measures, which occurred in less than one-third of crisis response operations. Also, tax policy and tax administration reforms to improve revenue collection were notably less frequent.15World Bank. 2017. Crisis Response and Resilience to Systemic Shocks: Lessons from IEG Evaluations. Washington DC: World Bank. See also IEG (Independent Evaluation Group). 2010. The World Bank Group’s Response to the Global Economic Crises, Phase I. Washington, DC: World Bank; and IEG. 2012. The World Bank Group’s Response to the Global Economic Crisis, Phase II. Washington, DC: World Bank.

- An assessment of the degree to which knowledge on public expenditures informed the design of DPF operations found that public expenditure reviews or similar analytics informed most DPF operations in some way, but that the quality of integration of that knowledge into the DPF design varied, in part depending on the quality and length of the policy dialogue and World Bank engagement, and trust between the World Bank and the client government. The main areas that informed DPF operations were public sector governance, social development, and human development. Medium-term expenditure frameworks, budgeting, and public financial management were the most common issues.16World Bank. 2015. How Does Knowledge Integrate with the Design of Development Policy Operations? Washington, DC: World Bank.

- Policy-based lending in the environment sector, which has grown significantly since 2005, was used to pursue broader sectoral and multisector goals related to climate change and the environment. It was most effective “when policy issues are the main barrier to improving environmental outcomes, rather than capacity or other issues.”17World Bank. 2016. Lessons from Environmental Policy Lending. Washington, DC: World Bank. pp. x-xi.Clear theories of change and well-designed results frameworks, analytical work, and technical assistance were identified as important factors influencing design and outcomes, while monitoring and evaluation frameworks were often weak.

- An IEG empirical analysis of success factors in DPF operations in low-income countries found that “improving ‘relevance of design’ is key for achieving better DPF outcomes: it requires congruence between policies supported and project development objectives pursued.” This study also found evidence of analytical underpinnings, macro policies, and government ownership affecting the success of DPF operations. Interestingly, DPF operations with development partners using joint policy assessment frameworks have not been associated with better outcomes than other DPF operations with otherwise similar characteristics.18World Bank. 2018. Maximizing the Impact of Development Policy Financing in IDA Countries: A Stocktaking of Success Factors and Risks. IEG meso-evaluation. Washington, DC: World Bank. p. 7.

- An independent reassessment of the quality of macro-fiscal frameworks in DPF operations found that these frameworks were largely internally consistent and credible, noting some improvement over time. In many cases, the quality appeared to be related to the alignment with the International Monetary Fund and World Bank’s analytical work in the macro-fiscal area. At the same time, the assessment found weaknesses in the following areas: (i) the ambition of macro-fiscal frameworks in some stand-alone operations and in the links between objectives and fiscal measures, (ii) the credibility of the framework in view of the government’s track record, political economy factors, treatment of risks, or institutional fiscal rules, and (iii) the robustness of the debt sustainability analysis.19World Bank. 2015. Quality of Macroeconomic Frameworks in Development Policy Operations. Washington, DC: World Bank.

- 13World Bank. 2015. Quality of Results Frameworks in Development Policy Operations. Washington, DC: World Bank.

- 14World Bank. 2016. Findings from Evaluations of Policy-Based Guarantees. Washington, DC: World Bank.

- 15World Bank. 2017. Crisis Response and Resilience to Systemic Shocks: Lessons from IEG Evaluations. Washington DC: World Bank. See also IEG (Independent Evaluation Group). 2010. The World Bank Group’s Response to the Global Economic Crises, Phase I. Washington, DC: World Bank; and IEG. 2012. The World Bank Group’s Response to the Global Economic Crisis, Phase II. Washington, DC: World Bank.

- 16World Bank. 2015. How Does Knowledge Integrate with the Design of Development Policy Operations? Washington, DC: World Bank.

- 17World Bank. 2016. Lessons from Environmental Policy Lending. Washington, DC: World Bank. pp. x-xi.

- 18World Bank. 2018. Maximizing the Impact of Development Policy Financing in IDA Countries: A Stocktaking of Success Factors and Risks. IEG meso-evaluation. Washington, DC: World Bank. p. 7.

- 19World Bank. 2015. Quality of Macroeconomic Frameworks in Development Policy Operations. Washington, DC: World Bank.

Evolving Framework for Evaluating World Bank Development Policy Financing

Until 2018, the World Bank used similar approaches for self-evaluation and validation of World Bank investment project financing (IPF) and DPF operations. The main difference was that efficiency (i.e., cost–benefit analysis) was not assessed for DPF operations because of the methodological difficulties in assigning costs, benefits, and weights to economic reforms underpinning DPF operations compared with the outputs supported by traditional investment projects. To assess the efficiency of a DPF operation, an evaluation would have to determine (i) whether more reform or more impactful reform could have been obtained for the same amount of budget support, or (ii) whether the same reforms could have been secured with less budget support. Given the nature of a budget support operation, a credible assessment of either would not have been feasible.

In September 2018, the World Bank and IEG adopted IPF-specific evaluation guidelines. Among the changes adopted, the rating for borrower performance was dropped so the assessment could be focused on how World Bank staff adapted and responded to borrower-related challenges. Self-evaluation and validation of DPF operations continued to use the preexisting guidelines.

The World Bank recognizes that budget support operations have features that require a different approach to evaluation when compared with investment project lending. For example, the specific prior actions required for DPF disbursement alone are rarely sufficient to achieve the program objectives, especially in the context of a multisector operation. Additional actions by governments and complementary support from investment projects and development partners are usually needed.

The trajectory of reforms supported by DPF are generally part of broader and longer-term policy-making efforts. This makes attribution of the development objectives to DPF operations particularly difficult. It also presents challenges in articulating a complete results chain based solely on the prior actions in the operation. Moreover, while supervision of a multi-year investment project is conceptually clear, it can be of lesser importance for a standalone DPF operation given that prior actions, by definition, are completed before approval (although monitoring of progress toward targets remains important).

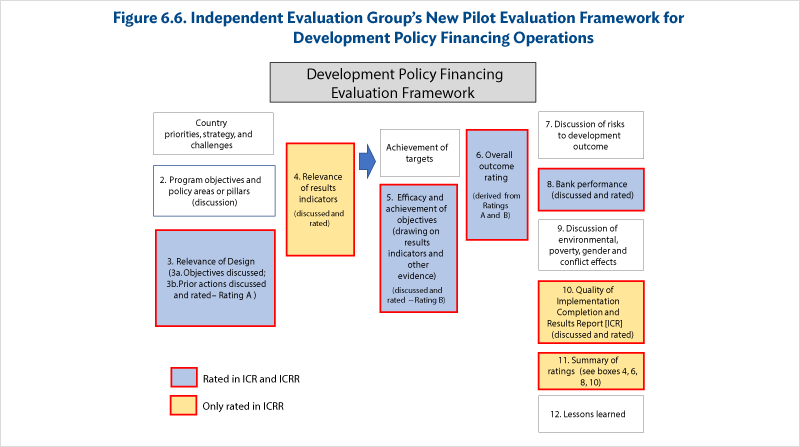

To improve the operational relevance of its work, IEG recently adopted changes to the structure and content of its evaluations and validations of DPF operations. This was in part in response to changes in ICRs (self-evaluation) that the World Bank has adopted. The new IEG framework for evaluating budget support operations better reflects the characteristics of DPF. Figure 6.6 shows the main building blocks of the new DPF evaluation framework.

The main changes from the earlier framework relate to the assessment of relevance, results indicators, and World Bank performance. Instead of rating the relevance of objectives, IEG will rate the relevance of the prior actions supported by the operation (although the relevance of objectives will still be discussed).20The discussion of the relevance of the objectives considers the extent to which a particular objective should be a priority for the World Bank, taking into account the overarching World Bank-supported country development strategy.

- 20The discussion of the relevance of the objectives considers the extent to which a particular objective should be a priority for the World Bank, taking into account the overarching World Bank-supported country development strategy.

Assessing the Relevance of the Reform Actions Supported by the Operation

Prior actions are reforms that are required for Board approval of the loan and operation. They are designed to address important constraints on the achievement of the operation’s development objectives. This rating assesses the extent to which prior actions: (i) addressed meaningful constraints or had a major impact on the achievement of the project development objectives (PDOs), and (ii) made a substantive and credible contribution to achieving those objectives. In rating the relevance of prior actions, the IEG evaluator will attempt to: (i) ascertain the clarity and credibility of the results chain linking prior actions to the achievement of the objective, taking into account the adequacy of the analytical basis linking the prior action to the PDO (and lessons learned from similar operations or experiences in the particular client country or in similar countries), and (ii) assess the importance of prior actions to the achievement of outcomes. This approach is expected to result in more operationally relevant lessons.

Evaluating the Quality of Results Indicators

The new framework also sought to put more structure and rigor into the identification of meaningful results indicators. For the first time, IEG will systematically rate the relevance and quality of indicators in the results framework. Results indicators are rated to assess the extent to which they capture the contribution of the prior actions supported by the DPF operations in achieving the program development objectives (PDOs). Beyond assessing the link between the reforms supported by the operation and the objectives of the operation, the assessment will look for clarity with respect to the definition of each results indicator, its method of calculation, and the credibility and availability of the associated data. The latter dimension was included because a conceptually appropriate indicator for which there are no reliable or available data is of little use in monitoring progress toward the achievement of the relevant development objective.

By assessing the results indicators before assessing the achievement of targets, this approach should provide a better basis for assessing the adequacy of the evidence presented for the achievement of objectives (for example, if an outcome target is achieved for an indicator that does not capture the impact of prior actions well, this would not be considered strong evidence of the achievement of a development objective). It is hoped that, over time, this approach will create a feedback loop to help World Bank teams to improve the selection and design of indicators, thereby fostering a greater outcome orientation in DPF operations.

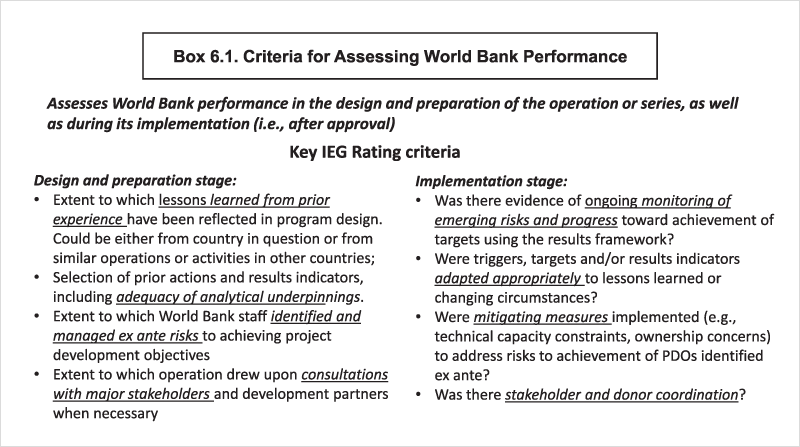

Assessing World Bank Performance

The assessment of World Bank performance has also been adapted to include greater granularity regarding the criteria to be used for assessment (Box 6.1). These criteria are deemed more operationally relevant to budget support operations, since they better reflect how World Bank staff engage with stakeholders and the operation during both preparation and the implementation. Particular attention is given to the adequacy of the ex ante assessment of risks to the achievement of objectives and the articulation and implementation of mitigating measures to reduce these risks. The importance of this discussion reflects, to some extent, the fact that the prior actions supported by a DPF operation are themselves generally not sufficient for the achievement of the PDOs. The ex ante discussion of risks forces a closer look at the results chain, linking the prior action to the desired outcome, drawing early attention to the additional support and complementary actions that will be required. The hope is that over time, this will promote more successful and better-informed risk taking in DPF operations.

Concluding Remarks

This chapter has reviewed the evolution of the use of DPF at the World Bank between 2005 and 2019 and its performance as reflected in the recent literature and Independent Evaluation Group (IEG) evaluations. The chapter also described recent changes to IEG’s evaluation framework for PBF operations. The principal conclusions are as follows.

- Policy-based lending has been an important financing instrument of the World Bank, accounting for about one-quarter of its total financing during 2005-19, but increasing to 40% in times of crises. It plays an important countercyclical role in developing countries. Budget support operations have supported short-term and longer-term policy and institutional reforms geared toward poverty reduction and shared prosperity (the World Bank’s twin corporate goals). There are several varieties of budget support in use, from standard, stand-alone operations, and programmatic series of operations to policy-based guarantees (PBGs) and deferred draw-down options. This makes development policy financing a flexible and versatile financing instrument that can be deployed in a wide variety of country contexts to support short-term goals (e.g., macroeconomic stabilization, natural disaster emergency, post-conflict budget financing support, and arrears clearance) and long-term goals (e.g., poverty reduction and shared prosperity). As a result, governments have frequently chosen this instrument, especially in times of crises, when national budgets are under stress, and quick-disbursing financing, combined with corrective policy actions, is an economic and social imperative.

- The COVID-19 crisis and its unprecedented global health, economic, and social impact has prompted the World Bank to rapidly scale up its financing to developing country recipients to cushion impact. To that end, the World Bank committed itself at the start of the pandemic to deliver $160 billion in overall financial support by the end of June 2021. In the event, $157 billion was delivered, of which $28 billion in development policy financing.

- IEG evaluations have generally assessed the World Bank’s DPF positively, with about four-fifths of assessments rated moderately satisfactory or higher. However, the share of operations rated satisfactory has declined, while the share rated moderately satisfactory has risen. There is evidence that elements of design have improved over time, including the quality of macroeconomic frameworks, results frameworks, and the use of knowledge on public expenditures.

- The World Bank has used DPF as a key instrument in supporting country clients in crisis. During crises such as the global financial crisis, the focus on fiscal management, effectiveness of public expenditures, and targeted social programs has supported countercyclical policies.

- The framework for evaluating development policy financing was recently revised in order to produce more operationally relevant assessments and findings, including with respect to the assessment of World Bank performance. IEG has similarly revised its validation framework for evaluations of DPF operations to give greater attention to the relevance and quality of prior actions, better results indicators, and more informed ex ante assessment of risks. IEG began using this new framework in late 2020.

This chapter provides a useful, concise, and well-written summary of the evolution of the World Bank’s approach to policy-based financing and methods to evaluate it. It shows the careful thinking undertaken by the World Bank as it has struggled to deliver effective support to countries, often in complex and difficult settings. As the chapter illustrates, policy-based financing has long been a major instrument of international development support, valued in the hundreds of billions of dollars annually across development agencies. Yet its breadth and complexity have made it exceedingly difficult to study, and evidence of its results remains elusive. This chapter helps to shed light on what is known, although for perhaps unavoidable reasons the picture is still incomplete.

The first point worth stressing is the practicality and value-added of the World Bank’s evaluation architecture. Over more than three decades the World Bank has designed, implemented, and continuously improved a cohesive structure to document results from all its operations—both investment and policy-based operations—in a practical and cost-effective manner. The process begins with a self-evaluation by the task team, whose members know the operation best. That self-evaluation—which uses standard criteria applicable to all similar operations—is then reviewed and validated by the Independent Evaluation Group (IEG). The fact that 100% of self-evaluations are validated creates an incentive for task teams to report accurately while also producing a complete database of operation-level reviews across the institution. As noted in the paper, IEG follows up in some cases with more in-depth evaluations and/or broader sector or thematic evaluations, adding further context and evidence on results. The entire evaluation architecture is oriented toward documenting activities and outcomes, and it creates opportunities for learning through self-evaluation and analysis.

The evaluation systems of other multilateral development banks (MDBs) are similar, in part due to concerted efforts at harmonization across the MDBs. In my personal experience on both sides of this self-evaluation and validation system—as both an operational and an evaluation manager—the system is useful, practical and cost-effective.

While recognizing the positive aspects of the evaluation architecture noted above, it is also important to emphasize what the system does not do, especially in the complex area of policy-based financing. These types of routine World Bank evaluations are not in-depth impact evaluations with rigorous causal inference. They do not compare performance against counterfactuals to identify and measure cause and effect. Occasionally it is possible to apply impact evaluation techniques to specific interventions in specific settings, but this is not feasible across the board given the breadth and complexity of most World Bank operations, particularly policy-based financing. Rather, in the World Bank system, task teams and evaluators seek to define relevant objectives for World Bank operations and then determine whether those objectives were achieved during the life of the operation, with some implicit assumptions but no rigorous analysis of causation.

The chapter describes in detail the criteria for self-evaluation and validation of development policy financing (DPF), which is the World Bank’s name for policy-based financing. These criteria have changed over time to reflect changes in the design of policy-based financing over time. When policy-based lending began in the World Bank in the 1990s, loans were disbursed in a series of tranches that were triggered by successful completion of policy reforms and institutional milestones. In contrast, the World Bank’s current DPF approach provides all the financing up-front, upon completion of a small number of key prior actions. This differs from the policy lending of the European Union, for example, which has a performance element and disburses in part on the achievement of results.

The World Bank’s approach thus puts a very heavy weight on a small number of upfront policy and institutional changes that it considers key to the country’s success. While having a small number of prior actions simplifies the lending process and focuses the World Bank’s oversight, it runs the risk that the assumptions regarding the impact of reforms may be wrong. Indeed, over time the consensus on what constitutes good policies has to some extent shifted, and it is likely that the prior actions and results indicators of many policy loans of the 1990s would now be seen as problematic by World Bank staff and evaluators. The World Bank’s heavy reliance on selected prior actions calls for an equally determined analysis of the effect of these policy and institutional changes whenever possible. Yet in practice there are few opportunities for the World Bank to follow up with careful analysis of these effects after the completion of prior actions and DPF disbursement.

Recently the World Bank has moved from rating the relevance of the DPF operation’s objectives (the standard approach in evaluations of investment operations) to rating the relevance of the prior actions, which are the only conditions for the operations that are directly within the World Bank’s control. The World Bank is also putting greater weight on evaluating the relevance and quality of the operation’s results indicators, World Bank performance, and the treatment of risk. These judgments are largely qualitative, and one person’s judgment may differ from another’s. To ensure these ratings are robust, it would be helpful to track whether guidelines, dialogue, and practice are converging in reasonably common standards across operations and over time.

An important aspect of DPF operations missed by the World Bank’s evaluation approach is the impact of the resource transfers themselves, i.e., the impact of spending the hundreds of millions of dollars transferred to recipient countries through development policy financing. Indeed, some have argued that the increased availability of funds for governments to spend may be the biggest impact of policy-based lending in practice, greater than the support to policy and institutional reforms provided in the loans.

Measuring the impact of the resource transfers would require knowledge of how those funds are actually spent, and this is not straightforward. DPF transfers are wholly fungible and are likely in practice to fund the “marginal expenditure” in the public budget—i.e., expenditure that could not otherwise be funded. This marginal expenditure could be in any sector—including infrastructure, social programs, defense, agriculture, and enterprise subsidies. It is by no means a foregone conclusion—nor is it even likely—that such marginal spending will be in the sectors with the policy reforms supported by the DPF. Although determining the marginal expenditure is likely to be difficult in practice, it might be possible to get a broad sense of the overall patterns of public spending with and without the extra resources transferred through the DPF. Trying to assess such changes in public spending in at least a few large DPF operations would be a worthwhile evaluative exercise for the World Bank.

Finally, the focus of most evaluations on individual DPF operations fails to capture the overall distribution of World Bank support and resource transfers among borrowing countries, although larger thematic evaluations may help to capture this dimension. Given the political incentives facing both borrower and donor governments, as well as bureaucratic incentives within the World Bank and other development institutions, it is not surprising that many resource flows go to middle-income countries—where it is easier to lend and where absorption power and interest rates are typically higher—than to low-income countries where the need may be greater and access to alternative financing sources more limited. This is particularly true in multilateral development banks, whose income and credit ratings are dependent in part on loan proceeds, in contrast to bilateral or multilateral donors (such as the EU) whose resources come wholly from governments.

The chapter reviews the data on the results of DPF operations over time and highlights several academic studies and thematic evaluations that have tried to draw further conclusions from these data. In addition to the inherent limitations on results measurement noted above, a few points stand out. First, there is a high prevalence of “moderately satisfactory” ratings for outcomes and World Bank performance. The difference between “moderately satisfactory” and “satisfactory” development policy financing—like the difference between “moderately satisfactory” and “moderately unsatisfactory” development policy financing—is based on the qualitative judgments of the validators, and this runs the risks of inconsistency noted earlier.

Second, thematic evaluations emphasize the prevalence and salience of DPF prior actions related to public financial management (PFM). Managing public finances is indeed an important and powerful responsibility of government that strongly influences the distribution of resources and effectiveness of public programs. It is an area that the World Bank has been able to focus on and influence relatively effectively through its operations. PFM has technocratic aspects— e.g., budgeting processes, computer systems, and auditing—to which the World Bank can bring needed expertise and resources. Other areas of governance reform, such as election systems, public employment, or direct anticorruption efforts, may be as (or even more) important for development outcomes but have been more difficult for the World Bank to address in the political environments in which it works. These sensitivities put limitations on what kinds of prior actions are feasible in DPF operations, which might also limit their potential development impact.

Third, the chapter also notes the value of the granularity gained through more in-depth evaluations of particular operations through project performance assessment reports (PPARs). Yet it is unclear to what extent operational World Bank staff read PPARs and integrate the findings into their operational work. Continued efforts to increase PPAR accessibility and impact, through both greater outreach and continued experimentation with content and process, would help to increase their usefulness. For example, in some instances comparative analyses of several similar operations may offer insights that reviews of individual projects do not. Doing some evaluations jointly with outside experts, other development organizations, or operational staff might also increase their ownership and visibility.

Finally, one of the cited academic studies concludes that the level of macroeconomic stability is positively associated with the success of DPF operations. As noted in the chapter, it is not possible to untangle causation, i.e., whether the World Bank’s operation influenced the country’s policies or good policies made it possible for the World Bank to lend. The fact that government ownership is also key to achieving outcomes and that “the World Bank’s policy lending is significantly and positively correlated with the quality of social policies and institutions” both reinforce the overwhelming importance of committed country counterparts.

In sum, the evidence strongly supports the finding that enlightened leadership, pro-development policies, and effective World Bank support go hand in hand, which is probably as much as can confidently be claimed. Attributing positive causal impact to the DPF operations themselves is not likely to be supported by the evaluation techniques available. But it is an important finding in today’s world that the World Bank can contribute to development by recognizing and supporting committed and effective leaders without having to prove that its actions led to that commitment.