Historical Development and Use of Budget Support by the European Union

The European Commission (EC)1The European Commission is the executive body of the EU and in charge of implementing the EU budget. first introduced budget support in the 1990s. The approach evolved in the context of conditionality reform and in response to the evolution of the aid effectiveness agenda. The current approach has been implemented since the beginning of the 2000s. The 1980s were marked by a gradual shift from using only project aid, whose effectiveness was often found to be limited by unfavourable policy and governance contexts, to the introduction of sector-wide approaches and structural adjustment programs. Sector-wide approaches enabled projects to be aligned with partner countries’ sector policies and enabled discussions about sector policies and sector governance. Sometimes these projects were implemented using the beneficiary country’s budgetary processes.2Program estimates are a form of on-budget support whereby the institution responsible for the budget and activities is assessed beforehand. At the same time, structural adjustment programs started providing direct budgetary support against prior conditions regarding major reform measures to be taken by the partner country. This support was accompanied by policy and governance discussions that aimed to improve the overall context for development and aid effectiveness. At the end of the 1990s, when evaluations of the effectiveness of structural adjustment programs implemented during the 1980s showed that using aid conditionalities did not generate sustainable policy reforms, budget support replaced structural adjustment programs: budget support was no longer triggered by the implementation of reform measures but was provided to eligible countries in support of their reform policies.

The form in which European Union (EU) budget support is implemented has evolved over time to reflect changing policy contexts and to take into account recommendations by external evaluations and by the European Court of Auditors. Unlike projects, budget support addresses the partner country’s overall conditions for economic and social development. EU budget support has always been provided exclusively in the form of grants. It is coherent and complementary with other EU aid implementation modalities, including projects, technical assistance, delegated cooperation, co-financing, blending, humanitarian aid, and emergency assistance.

The latest EU budget support policy was adopted in 20123The policy direction is set out in the 2011 Budget Support Communication ‘The Future Approach to EU Budget Support to Third Countries’, and corresponding Council Conclusions COM(2011) 638; 13 October 2011; 3166th Foreign Affairs Council meeting, Brussels, 14 May 2012 (http://www.consilium.europa.eu/uedocs/cms_Data/docs/pressdata/EN/foraff/130241.pdf).. Its guidelines were revised in 20174See European Commission. 2017. Budget Support Guidelines. Brussels. https://ec.europa.eu/international-partnerships/system/files/budget-support-guidelines-2017_en.pdf. to take into account the new European Consensus on Development that followed the international adoption of the UN 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and the Addis Ababa Action Agenda.

The EU’s approach to budget support has always involved four interrelated components acting together in support of partner countries’ policy implementation:

(i) policy dialogue with a partner country in order to reach agreement on the policies and reforms to which budget support can contribute;

(ii)performance assessment to achieve consensus on expected results and to measure progress achieved;

(iii)financial transfers to the Treasury account of the partner country once those results have been achieved and according to their degree of achievement; and

(iv)capacity development to enable countries to implement reforms successfully and to sustain results.

EU budget support is thus a performance-based modality, which provides a package of unconditional grant funding, capacity development and a platform for dialogue to partner countries in support of the implementation of their policies. Funding is totally fungible: it is an additional resource to domestic revenues and is used by the partner country’s government according to domestic budgetary planning, execution and oversight processes and using domestic public finance management (PFM) systems. EU budget support grants can thus be used for both recurrent and investment expenditure.

Policy dialogue is a fundamental component of EU budget support. The general conditions (regarding public policy, macroeconomic stability, public finance management and, since 2012, budget transparency and oversight) provide the overall framework for dialogue with the government and other stakeholders, while variable tranche indicators enable a more in-depth discussion on key reforms and policy results. Because funds are transferred to the budget, the EU is able to discuss general PFM issues, overall budget allocations and sector spending as well as its results with the partner countries’ authorities and other stakeholders. Due to the grant nature of the funding, the EU is particularly concerned that budget support should not be considered a substitute for efforts to raise revenues. Domestic resource mobilization is systematically raised in policy dialogue and is often supported through capacity strengthening and/or through the use of performance indicators. Monitoring of general policy outcomes and of sector-level policy processes, activities, outputs and, most importantly, outcomes are an essential input into the overall dialogue.

Although external experts hired in the context of technical cooperation can never be responsible for achieving the targets set for the agreed performance indicators,5Box ‘Ten aspects to consider when assessing a performance indicator’, in Annex 8 of the Budget Support Guidelines, op.cit., page 139. the capacity building most often associated with budget support is used to enhance the government’s capacity to design, implement, monitor, and evaluate policies and to deliver public services. Since EU budget support relies on the monitoring of performance indicators, preferably outcome indicators, strengthening of national monitoring frameworks and associated statistical systems is a priority. Attention is also systematically paid to promoting the active engagement of nongovernment stakeholders in these monitoring frameworks.

- 1The European Commission is the executive body of the EU and in charge of implementing the EU budget.

- 2Program estimates are a form of on-budget support whereby the institution responsible for the budget and activities is assessed beforehand.

- 3The policy direction is set out in the 2011 Budget Support Communication ‘The Future Approach to EU Budget Support to Third Countries’, and corresponding Council Conclusions COM(2011) 638; 13 October 2011; 3166th Foreign Affairs Council meeting, Brussels, 14 May 2012 (http://www.consilium.europa.eu/uedocs/cms_Data/docs/pressdata/EN/foraff/130241.pdf).

- 4See European Commission. 2017. Budget Support Guidelines. Brussels. https://ec.europa.eu/international-partnerships/system/files/budget-support-guidelines-2017_en.pdf.

- 5Box ‘Ten aspects to consider when assessing a performance indicator’, in Annex 8 of the Budget Support Guidelines, op.cit., page 139.

Eligibility for European Union Budget Support

EU budget support has always been subject to the satisfaction of eligibility criteria.6The eligibility criteria stem from EU financial regulations (see the 2018 EU Financial Regulation currently in force, Article 236). These criteria need to be met before a program is approved and throughout implementation, in particular before disbursements. Although these eligibility criteria have evolved over the past 20 years, they have stayed faithful to the same underlying principles: budget support is performance-based and uses a dynamic approach to assess eligibility, looking at the country’s past and recent performance in public policy, macroeconomics, public finance management (PFM), and budget transparency and oversight, against reform commitments. A stable macroeconomic environment, an established PFM system (including a budget and functioning external oversight) and a credible and relevant public policy are essential to achieving economic development and are thus crucial to the effectiveness of budget support.

The eligibility criteria for budget support are listed in Table 3.1.

Table 3.1. EU Eligibility Criteria for Budget Support at Approval and During Implementation

| Criteria at Program Approval | Criteria During Implementation |

| Public policy. Existence of a credible and relevant national and/or sector policy in place. | Public policy. Satisfactory progress in the implementation of the policy or strategy and continued credibility and relevance of that or any successor strategy |

| Macroeconomics.Existence of a credible and relevant program to restore and/or maintain macroeconomic stability | Macroeconomics. Maintenance of a credible and relevant stability-oriented macroeconomic policy or progress made towards restoring key balances |

| Public financial management. Existence of a credible and relevant program to improve public financial management, including domestic revenue mobilization | Public financial management. Satisfactory progress in implementation of reforms to improve public financial management, including domestic revenue mobilization, and continued relevance and credibility of the reform program |

| Budget transparency and oversight. The government has published either the executive’s proposal or the enacted budget within the previous or current budget cycle. | Budget transparency and oversight. Satisfactory progress with regard to the public availability of accessible, timely, comprehensive and sound budgetary information. |

While the first three criteria have always been linked to the provision of EU budget support, the inclusion of budget transparency and oversight as a stand-alone criterion resulted from the revised 2012 budget support policy. This revision also introduced the partner country’s commitment to EU fundamental values of human rights, democracy and rule of law as a precondition to the provision of general budget support. The explicit reference to domestic revenue mobilization was added when the guidelines were updated in 2017 in order to take into account the Addis Ababa Action Agenda of 2015.

Both an in-depth analysis of each of these eligibility criteria and an accompanying dialogue are undertaken prior to the formulation of a budget support program. This ensures that conditions for budget support effectiveness are in place, that the government is committed to the reforms the EU supports, and that it has the capacity and political back-up to implement them.

When the eligibility criteria are satisfied, the EU can provide budget support by transferring funds directly to the central bank of the partner country. These funds are then converted to the national currency, paid into the Treasury, and used to support national policy implementation using domestic systems, processes, and procedures. Funds cannot be used to build up foreign exchange reserves.7A specific clause in a budget support contract requires the partner country to provide documentary evidence that the Treasury account has been credited by the amount equivalent to the foreign exchange transfer at the exchange rate prevailing on the day funds were received. Budget support funds must be accounted as government revenues and included in the state budget. Responsibility for the management of these transferred resources rests with the partner government. These funds, like any other public monies, are subject to oversight by the national supreme audit institution and the parliament and subject to public scrutiny. In particular, the EU promotes the involvement of civil society organizations in order to foster domestic accountability.

The peculiarity of EU budget support lies in the disbursement of funds in a combination of fixed tranches, paid in full (or not at all) and variable tranches. Their payment is proportional to the progress in meeting benchmarks, as agreed at the beginning of the program. On average, the split of funds delivered through fixed and variable tranches is 50%.8However, great variation can be seen across countries; some programs provide only fixed tranches or only variable tranches in a given year. The disbursement of each tranche is subject to the eligibility criteria mentioned above. Variable tranches provide an incentive for performance and allow focused discussions on key reforms and results to be held. They give the EU an effective and predictable way to adjust payment levels to the country’s achievements and to discuss issues around under-performance without having to entirely stop program implementation.

In its mechanics, the EU’s definition of budget support is exactly the same as that of the Development Assistance Committee of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD-DAC), but with the additional aspect that disbursements take place only when eligibility criteria are satisfied and targets are met. EU budget support is therefore strongly focused on results: it relies on a qualitative assessment of the progress made in the four areas of eligibility (macroeconomic policies, PFM reform, sector policy implementation, and budget transparency and oversight) as well as on specific performance indicators (preferably outcome indicators) which measure the progress in the uptake of services delivered to the population. The performance indicators and their targets are drawn from partner countries’ own policy monitoring matrixes, are agreed upfront at the beginning of a program, and can only be changed under exceptional circumstances.9In addition, changes to indicators or their targets have to be agreed no later than the end of the first quarter of the implementing year to which the result targets refer. In practice, as results of year N-1 are most often assessed mid-year N when outcome data become available, it is often too late to agree changes for subsequent years if data reveal weaknesses and/or deviations from expected outcomes. This rule ensures, first, that adequate attention is brought to the choice and definition of performance indicators used for variable tranches and, second, that there is a joint EU-partner commitment to reach the agreed targets. Funds are released once progress is demonstrated, both on overall policies (fixed tranches) and on the specific performance indicators (variable tranches). The average disbursement rate of the 199 EU budget support programs approved and implemented between 2014 and 2019 was 83%. Most of the non-disbursed 17% came from the partial disbursement of variable tranches (when not all performance indicators reached their agreed targets). The remainder stems from fixed tranches not being disbursed (when program implementation was severely disrupted or eligibility to budget support not met any longer).

- 6The eligibility criteria stem from EU financial regulations (see the 2018 EU Financial Regulation currently in force, Article 236).

- 7A specific clause in a budget support contract requires the partner country to provide documentary evidence that the Treasury account has been credited by the amount equivalent to the foreign exchange transfer at the exchange rate prevailing on the day funds were received. Budget support funds must be accounted as government revenues and included in the state budget.

- 8However, great variation can be seen across countries; some programs provide only fixed tranches or only variable tranches in a given year.

- 9In addition, changes to indicators or their targets have to be agreed no later than the end of the first quarter of the implementing year to which the result targets refer. In practice, as results of year N-1 are most often assessed mid-year N when outcome data become available, it is often too late to agree changes for subsequent years if data reveal weaknesses and/or deviations from expected outcomes. This rule ensures, first, that adequate attention is brought to the choice and definition of performance indicators used for variable tranches and, second, that there is a joint EU-partner commitment to reach the agreed targets.

Types of Budget Support

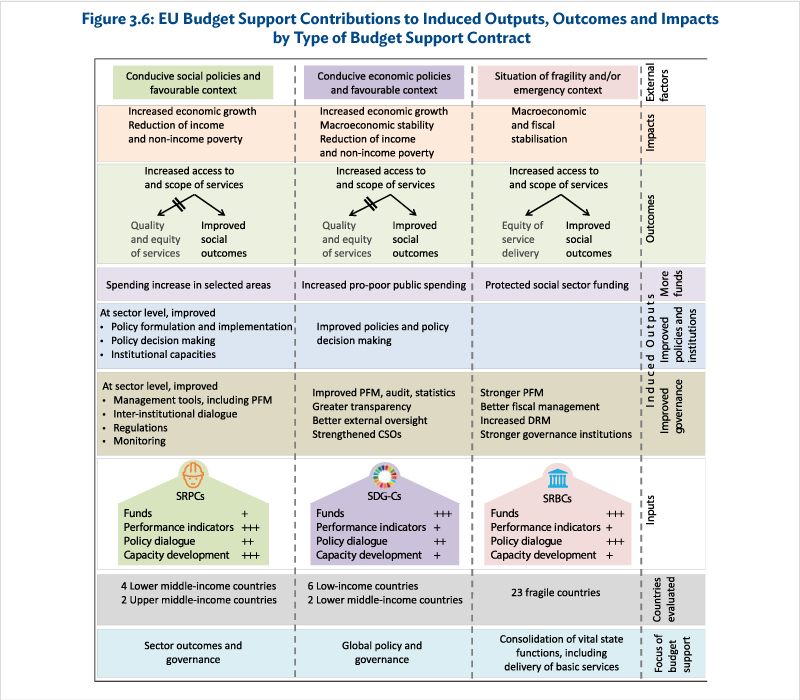

Whereas previous EU budget support had been implemented as general or sector budget support, the 2012 policy introduced a further differentiation of the types of budget support and strengthened its contractual aspects. The EU now offers three types of budget support contracts:

- Sustainable Development Goals contracts (SDG-Cs).10Previously known as good governance and development contracts (2012–2017). These are provided at the macroeconomic level to support implementation of the overall national development strategy. A contract covers several SDGs and the approach is comprehensive and crosscutting. The partner country’s commitment to the respect of the EU’s fundamental values is a precondition for this type of support. The SDG-Cs call for stability and confidence in the overall policy stance and democratic governance of the partner country. This type of contract has an average duration of 4 years but can run from 3 to 6 years.

- Support for fragile and transition countries. This contract was introduced in 2012 and takes the form of a state and resilience building contract (SRBC).11Previously known as state building contracts (2012–2017). The resilience dimension was added in 2017. The contract offers general budget support in the case of political transitions, post-disaster situations, and crises (such as the COVID-19 pandemic). Eligibility for this type of support includes a forward-looking approach, based on the partner country’s political commitment to reform and to fundamental values. SRBCs can last from 1 year (for countries recovering from a crisis) to 3 years (in cases of more structural fragility). The average duration of SRBCs is 2.5 years.

- Support for sector policies and reforms. This is provided through sector reform performance contracts (SRPC), which account for the largest share of EU budget support (about 80%). SRPCs are more narrowly focused than the other two types of contracts and concentrate on one or a few closely related SDGs. They aim to improve governance and service delivery in a specific sector or a set of interlinked sectors. The average duration of SRPCs is 4 years.

Significance of European Union Budget Support

Over the period 2000–2019, new budget support commitments amounted to an average of €1.84 billion per year. This varied from €1.1 billion per year on average during 2000–2006, to €2.3 billion per year on average during 2007–2013 and €2.2 billion per year on average over 2014–2019.

Over the period 2000–2019, the EU provided budget support to about 100 countries.12This includes EU overseas countries and territories. As of 2015, EU sector budget support started being implemented in the Western Balkans for candidates and potential candidates for EU membership. In the most recent period, 2014–2019, just over €13 billion was committed to 231 budget support programs in 94 countries. The average value of a budget support contract was €56.4 million (equivalent to €15.4 million per contract per year on average). General budget support is at the high end of the scale, with an average amount of €99.4 million per SDG-C, equivalent to €25.5 million per year per contract, and €80 million on average per SRBC, which is equivalent to €32.5 million per contract per year. Sector budget support contracts are the most common type of contract and have the lowest average values. Over the period, 179 SRPCs were provided for an average value of €12.3 million per contract per year.

On average, the European Commission estimates that budget support amounts to 35%–40% of its country programmable aid, a very significant part of its portfolio of direct cooperation with partner countries.

- 12This includes EU overseas countries and territories.

Beneficiaries of EU Budget Support

Evolution of General and Sector Budget Support

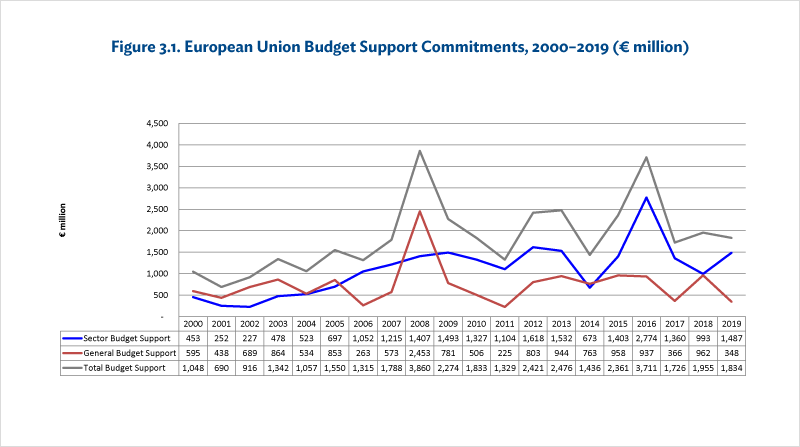

EU budget support is provided as sector budget support (SRPCs) and as general budget support (which includes both SDG-Cs and SRBCs). Between 2000 and 2005, general budget support was the main type of budget support provided by the EU, representing 60% of the total budget support value (Figure 3.1). Over time, sector budget support has increased its share.

Source: European Commission, Unit E1 ‘Macro-economic Analysis, Fiscal Policies and Budget Support’

Sector budget support has been increasingly used by the EU since 2006, due both to the decreased use of general budget support (linked to the requirement that countries commit to fundamental values to be eligible for such support introduced in 2012), and to the introduction of sector budget support to the Western Balkans in 2015. Sector budget support represented 67% of all budget support provided over the period 2014–2019. In 2020, the EU increased its use of state resilience and building contracts in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, including in the Western Balkans, where hitherto only sector budget support could be provided.

Budget support is an effective and flexible instrument for many situations, including emergencies, which require a fast-track response to help stabilise a situation and to ensure the crisis does not deteriorate further at the expense of the population. New budget support commitments amounted to €3.86 billion in 2008 and remained well above average in 2009 and 2010. This partly reflects the EU’s programming cycle (preparations for new budget support programs launched in 2007 started being approved by the end of 2008 and the beginning of 2009); partly the introduction of a few very large Millennium Development Goals contracts (the precursor of SDG-Cs); and partly the EU’s reaction to the 2007–2009 global financial crisis, which resulted in the provision of budget support to countries suffering from economic collapse and/or soaring food prices.

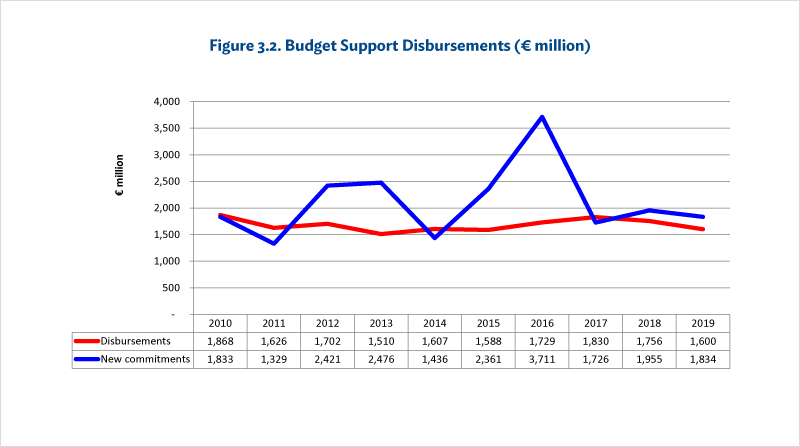

EU budget support disbursements (Figure 3.2) represented, on average, €1.68 billion a year over the period 2010–2019; 15% of EU total official development assistance (ODA) per year, or an estimated average of 29% of country programmable aid disbursements per year.

Since 2012, a new type of fast-track contract, the state building contract (SBC) has been used to support countries facing a crisis, including natural disasters or health pandemics. This type of support to countries in a situation of fragility or transition has overtaken SDG-Cs as general budget support. SBCs were introduced in 2012 and amounted to €180 million in commitments, or 21% of general budget support in 2012. Since 2017, they have been known as state and resilience building contracts (SRBCs). By 2019 they represented 88% of all new general budget support. Since 2012, just under €4 billion has been provided to fragile states in the form of SBCs or SRBCs.

Budget Support Beneficiaries by Income Status Group

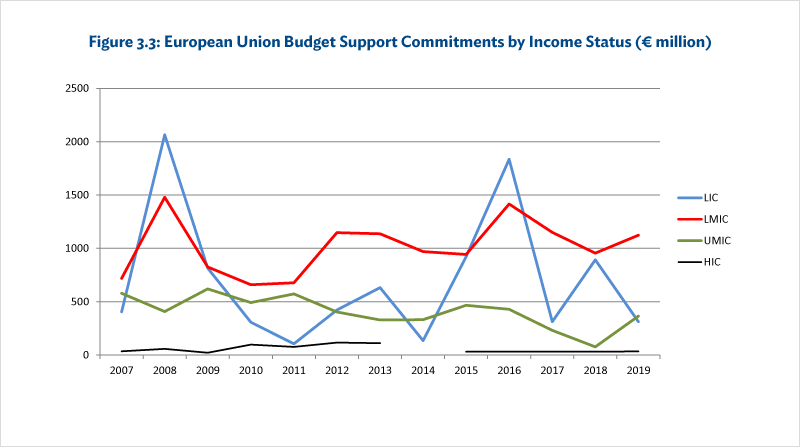

Low-income countries (LIC) and lower middle-income countries (LMIC) are the primary beneficiaries of EU budget support, accounting for 81% of total commitments during 2007–2019. During 2007–2013, 23 LICs benefited from a total amount of €4.75 billion through budget support, with the largest amounts going to Burkina Faso, Tanzania, and Mozambique. During 2014–2019, 18 LICs received €4.4 billion, with the largest recipients being Burkina Faso, Afghanistan and Niger (each receiving €450–€500 million). As seen above and in Figure 3.2, countries in a fragile or crisis context have been increasingly important recipients of budget support since 2012.

Since a number of LICs have moved to LMICs status, the group benefiting the most from EU budget support has changed over time. During 2007–2013, 33 LMICS received budget support, of which Morocco, South Africa and Egypt received the highest amounts (between €500 million and €1.3 billion each over 2007–2014). During 2014–2019, 63 LMICs received budget support, with the highest amounts provided to Morocco, Tunisia and Ukraine.

Upper middle-income (UMIC) and high-income countries (HIC) were minor recipients of budget support. Most of the 36 UMICs and HICs benefiting from budget support during 2007–2013 were small-island states receiving budget support at the end of their trade protocol with the EU, which protected sugar production. During the more recent period 2014–2019, 14 HICs received budget support, with 70% of the amounts going to Eastern European states.

In terms of geographical areas, Africa remains the largest recipient of EU budget support, accounting for 60.4% of all budget support funding during 2014–2019 (€7.86 billion), followed by Asia and Eastern Europe (14% each) and Latin America (5%). The remaining 6% is accounted for by overseas countries and territories, and Caribbean and Pacific islands.

Policy Reforms Supported by European Union Budget Support, 2014–2019

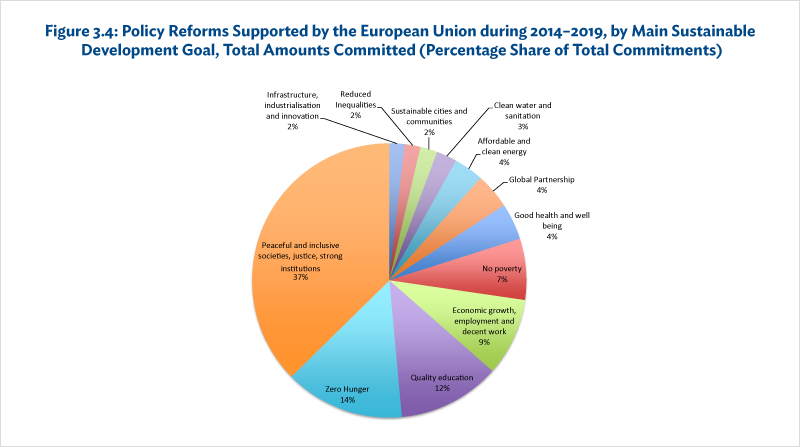

The EU budget support portfolio directly or indirectly contributes to improvements in macroeconomic management, PFM, domestic revenue mobilization (DRM), budget transparency and oversight, and sector policies, through the in-depth analysis and policy dialogue of budget support eligibility criteria. In many cases, improvement in these areas also benefit from complementary technical assistance and specific budget support programs in support of SDG 16.

In addition, EU budget support supports reforms across a wide range of sectors and sub-sectors, with a dominant focus on governance issues (SDG 16), poverty reduction (SDG 1) and basic services (SDGs 3, 4, and 6)—Figure 3.4. Gender (SDG 5) and the fight against inequality (SDG 10) were supported as major cross-cutting issues. Gender was supported in 41.6% of budget support program amounts and the fight against inequality 13.2%, of budget support amounts over the period 2014–2019.

The EU used its fast-disbursing SRBCs13SRBCs can be prepared and disbursed very rapidly (in a matter of weeks rather than years) compared to other types of budget support. to provide much needed support to health expenditure in countries hit by Ebola (Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone). This support either facilitated the maintenance of health expenditure (Guinea) or increased it quite dramatically. For instance, in Sierra Leone, Ebola-related fixed-tranche disbursement helped to increase the share of recurrent spending of the health sector from 13.3% of GDP in 2011 to 19.7% in 2014, 20% in 2015, and 16.5% in 201614Source: Evaluation of EU State Building Contracts (2012-2018), Main report, page 58. https://ec.europa.eu/international-partnerships/system/files/state-building-contracts-2012-2018-eval-dec-2020-main-report_en.pdf. In the same way, the EU provided SRBCs to Nepal following the earthquake in 2015, Fiji and Dominica for post-cyclone recovery in 2016, and Dominica following hurricane Maria in 2018.

Where required, existing budget support operations can be amended to release larger amounts more quickly than originally planned. This was the case at the beginning of 2020, in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, when some amounts planned for variable tranches in existing contracts were converted to fixed tranches and disbursed ahead of their planned schedule, in order to help governments fund COVID-19 preventive measures at very short notice. Some 2021 tranches have also been frontloaded to increase the EU’s global response to the crisis. Where undisbursed funds from previous tranches were available, they were used to top-up existing programs.

- 13SRBCs can be prepared and disbursed very rapidly (in a matter of weeks rather than years) compared to other types of budget support.

- 14Source: Evaluation of EU State Building Contracts (2012-2018), Main report, page 58.

https://ec.europa.eu/international-partnerships/system/files/state-building-contracts-2012-2018-eval-dec-2020-main-report_en.pdf

Cooperation Between the European Union and the International Monetary Fund

The EU cooperates closely with the International Monetary Fund (IMF). First, IMF assessments are essential to inform EU decisions regarding eligibility for budget support (for the macroeconomic policies, but also when relevant for the assessment of PFM, DRM, and transparency reforms and for the financing of development or sector policy). This takes place in the context of Article IV consultations or of IMF programme reviews. IMF assessments are equally important for informing payment decisions. Nevertheless, in line with the EU’s policy and regulatory framework, EU decisions on new budget support programs or budget support payments are not bound by IMF positions.

Second, the EU has signed a PFM Partnership Program with the IMF on the global architecture and policy agenda for PFM, DRM, and transparency. This program complements funding granted to the IMF regional technical assistance centres. The EU has been the top funder of the IMF in the field of capacity development in the period 2018-2020. At the country level, IMF technical review or support missions complement technical assistance and capacity development projects that are funded and implemented directly by the EU.

Evaluations of EU Budget Support, 2010–2019

Since 2010, independent evaluation teams have undertaken 17 general and sector budget support evaluations. These were managed by evaluation management groups, comprising representatives of partner countries and funding agencies, under European Commission management. As shown in Table 3.2, of the total 17 evaluations undertaken, 11 were multi-donor evaluations assessing the joint effects of all the general and sector budget support operations financed by different development partners. Evaluation periods differed slightly across all 17 evaluations, which stretched from 1996 to 2018.

Table 3.2: Budget Support Evaluations Since 2010aThe evaluations can be found on https://ec.europa.eu/international-partnerships/strategic-evaluation-reports_en.

|

Type of Budget Support EvaluatedbThe terminology used is that of the European Commission’s 2017 Budget Support Guidelines. https://ec.europa.eu/international-partnerships/system/files/budget-support-guidelines-2017_en.pdf |

Country Income StatuscCountry income status during the period of budget support provided (indicated in the last column of the table). |

Country and Completion Year of the Evaluation |

Multi-Donor Budget Support and Evaluation |

Period Covered |

|

General budget support, SDG-Cs |

LMIC LIC LIC LIC LIC LIC LIC LMIC |

|

Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes |

1996–2008 2003–2009 2005–2010 2004–2011 2005–2012 2004–2013 2009–2014 2005–2015 |

|

General budget support, SRBCs |

LIC LIC LIC |

|

Yes Yes No |

2002–2015 2005–2013 2012–2018 |

|

Sector budget support, SRPCs |

LMIC LMIC UMIC UMIC LMIC LMIC |

|

No Yes No No No No |

2000–2011 2005–2012 2006–2014 2009–2016 2011–2016 2010–2017 |

LIC = low-income country, LMIC = lower middle-income country, SDG-C = Sustainable Development Goals contract, SRBC = state and resilience building contract, SRPC = sector reform performance contract, UMIC = upper middle-income country

- aThe evaluations can be found on https://ec.europa.eu/international-partnerships/strategic-evaluation-reports_en.

- bThe terminology used is that of the European Commission’s 2017 Budget Support Guidelines. https://ec.europa.eu/international-partnerships/system/files/budget-support-guidelines-2017_en.pdf

- cCountry income status during the period of budget support provided (indicated in the last column of the table).

- dThis evaluation assessed the use of the SRBC instrument in the 23 countries where it had hitherto been provided. See https://ec.europa.eu/international-partnerships/evaluation-eu-state-building-contracts-2012-2018_en.

Methodology

The OECD-DAC methodological approach15See Evaluating Budget Support: https://www.oecd.org/dac/evaluation/evaluatingbudgetsupport.htm. to evaluating budget support, sometimes known as the three-step approach, was used in all the evaluations listed in Table 3.2. This approach acknowledges that budget support cannot deliver outcomes and impacts by itself, as it can only contribute to the outcomes and impacts that are achieved through the implementation of governmental policies and public spending. EU budget support focuses on the results and, in particular, on the outcomes of the policies it supports. It leaves the partner country to take full ownership of its policy process and full responsibility for the accountability of its results, while supporting it with discussions, advice, funding, capacity development, and results monitoring. Because of this approach, the EU cannot claim to have directly delivered any of the achieved outcomes but, since it has supported governments in reaching these results, it can claim that it has (or has not) contributed to the achievement of these results.

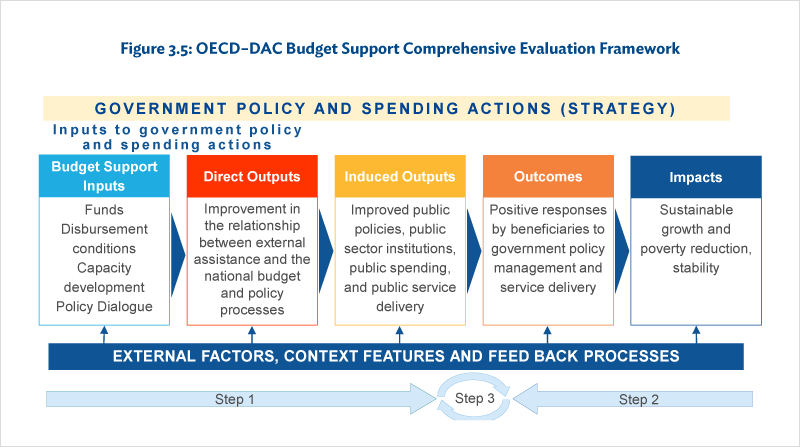

The OECD–DAC methodology is particularly well suited to evaluating EU budget support because it unravels and assesses the paths through which budget support inputs may have contributed to the improvement of public policies and institutions and also the extent to which these improved public policies and spending actions have caused changes in social and economic development.

In many cases, the EU is not the only development partner to have provided support for government policies. When evaluating budget support, the combined effects of all budget support operations in a given period of time in a country are considered. Given the influence of external factors, budget support evaluation cannot rely on a causality analysis and needs to differentiate between: the budget support’s direct outputs (which can be expected to be produced directly by the budget support’s inputs, e.g., funds, policy dialogue, technical assistance and performance measurement); and its induced outputs (which are situated at the level of public policy, institutional and spending changes, and which result from budget support direct outputs influencing and interacting with government processes).

To accommodate this complexity, the OECD–DAC approach to budget support evaluation is undertaken in three steps (Figure 3.5)

Source: Adapted from https://www.oecd.org/dac/evaluation/evaluatingbudgetsupport.htm.

Each step follows a very distinct logic:

- Step 1. Identifies the combined effects of all budget support provided to the country on aid, policy and institutional processes. The causal relationships between the budget support provided and changes in public policies, institutions, services delivery, and spending are analysed, recognizing that these changes are determined by the government and its policies beyond the budget support package. This step analyses the contribution of budget support inputs to outputs and induced outputs.

- Step 2. Identifies changes observed in outcomes and impacts as regards social and economic development which were targeted by the government policies supported (e.g, use of public services, business confidence and other sector outcomes) and analyses the factors determining these changes. These determining factors include public policy actions and also factors outside the government’s control (e.g., private sector and civil society initiatives, other aid programs, and external factors). Step 2 links changes observed at outcome and impact levels to their explanatory factors. It usually involves an econometric regression analysis of change in two or more sectors supported by budget support.

- Step 3. Combines the results of step 1 and step 2. The analysis teases out the extent to which budget support, through its contribution to government policies and spending actions, may have contributed to the outcomes and impacts identified.

This evaluation framework assumes that there are two main driving forces which generate most of the changes in induced outputs and outcomes:

- the flow-of-funds effects resulting from the provision of the budget funds; and

- the policy and institutional effects resulting from the interplay of budget support funding, policy dialogue, capacity building and disbursement conditions (performance indicators) with domestic processes of policy making, budget formulation and budget execution.

Both streams of effects can be traced up to the induced output level, while also recognizing that other factors are at play. The contribution analysis of step 1, when confronted with the results of the attribution analysis undertaken in step 2, allows the evaluator to assess the contribution of budget support to the successes and/or failures of the government policies and strategies, in relation to the outcomes and impact that the budget support programs intended to promote. This last step 3 analysis is a qualitative contribution analysis.

- 15See Evaluating Budget Support: https://www.oecd.org/dac/evaluation/evaluatingbudgetsupport.htm.

Key Questions and Issues

Evaluation questions are country- and sector-specific and follow a similar pattern. An evaluation generally has no more than 12 questions. The first questions concern the relevance of the budget support and assess the extent to which the support responded to the institutional, political, economic, and social context of the country or sector and was coherent with government priorities. Subsequent questions analyse the direct effects of budget support inputs on aid processes, macroeconomic management, public finance management, the level and composition of public spending, policy formulation and implementation processes, and governance. Answers to these questions allow for the completion of step 1 of the evaluation methodology.

The scope of the budget support being evaluated (general and/or sector budget support) usually determines the number of questions asked under step 2 of the evaluation, with usually one question per theme or sector. These questions investigate the effectiveness and impact of the policies being supported. They start by identifying the changes in the competitive nature of the economy, in areas pursued by the budget support programs, in income and non-income poverty, in the use and quality of public services and their impact on the livelihood of the population. Once these changes are identified, the extent to which they are related to changes in macroeconomic management, PFM systems, sector policy or policy processes, and/or to other factors, is assessed. The scope of step 2 and the focus of the questions depends on the data available and may be limited due to the evaluation’s budget and time constraints.

Step 3 is a conclusive evaluation question, which assesses the extent to which budget support has contributed to the policy and institutional changes that were found to be important factors in reaching the observed outcomes and impacts at sector and country levels. This question provides a qualitative assessment of the efficiency, effectiveness, and sustainability of the budget support provided.

Limitations of the Evaluation Approach and Recommendations for Improvement

This three-step evaluation methodology was tested several times before being adopted by the OECD-DAC network on development evaluation in 2012.16The methodology was tested in evaluations of budget supports in Mali, Zambia, and Tunisia in 2011. See https://www.oecd.org/countries/zambia/evaluatingbudgetsupport.htm. It was re-assessed in 2014 when the EU commissioned a synthesis of seven evaluations undertaken since 2010, looking at the strengths and weaknesses of the three-step approach.17In addition to the three pre-cited evaluations of 2011, the synthesis included the evaluations of budget support in Tanzania (2013), Mozambique (2014), South Africa (2013) and Morocco (2014). See https://www.oecd.org/dac/evaluation/Evaluation-Insights-Evaluating-the-Impact-of-BS-note-FINAL.pdf The specific tools and evaluation techniques used by each evaluation team were compared and assessed in order to develop recommendations on possible improvements. The recommendations covered methodological aspects as well as managerial and process issues.

- A contextual analysis should be included in each evaluation.

- Step 2 analysis18Most of the evaluations relied on the analysis of secondary data sourced from existing administrative or survey data. Primary data collection was mostly limited to information gained through focus group discussions and structured interviews. The synthesis discussed the possibility of undertaking specific survey work to provide primary data for a more precise and focused analysis. should consider the possibility of using secondary rather than primary data analysis and/or more qualitative approaches (such as benefit–incidence surveys or perception surveys).

- Development partners’ management responses to evaluation recommendations need to be strengthened.

- Evaluation reporting formats should be simplified.

- The classification and presentation of evidence collected should be simplified to facilitate comparability across evaluations.

In addition, the study noted that the evaluation approach could become an integral part of the domestic policy processes if it was led by the country rather than by the development partners.

These recommendations were based on seven evaluations. Looking across the 17 evaluations examined in this chapter, it is clear that the application of the methodology provided more robust results at the step 1 level for sector budget support than for general budget support.19The evaluations can be found on https://ec.europa.eu/international-partnerships/strategic-evaluation-reports_en This was not due to the type of budget support but to the fact that, by coincidence, in five of the six sector budget supports evaluated, recipient governments chose to earmark EU funds to specific (and narrowly defined) spending programs. This made the effects of budget support more traceable and allowed for a counterfactual approach to be taken for step 1. At the same time, these five countries stood out for their poor monitoring of policy actions and outcomes, making it more difficult to undertake the step 2 analysis. To assess policy and budget support effectiveness, the 17 evaluations confirmed that strengthening partner countries’ statistical institutions, statistical and monitoring systems, and accountability systems through improved and regular policy impact analysis needs to remain a priority.

- 16The methodology was tested in evaluations of budget supports in Mali, Zambia, and Tunisia in 2011. See https://www.oecd.org/countries/zambia/evaluatingbudgetsupport.htm.

- 17In addition to the three pre-cited evaluations of 2011, the synthesis included the evaluations of budget support in Tanzania (2013), Mozambique (2014), South Africa (2013) and Morocco (2014). See https://www.oecd.org/dac/evaluation/Evaluation-Insights-Evaluating-the-Impact-of-BS-note-FINAL.pdf

- 18Most of the evaluations relied on the analysis of secondary data sourced from existing administrative or survey data. Primary data collection was mostly limited to information gained through focus group discussions and structured interviews. The synthesis discussed the possibility of undertaking specific survey work to provide primary data for a more precise and focused analysis.

- 19The evaluations can be found on https://ec.europa.eu/international-partnerships/strategic-evaluation-reports_en

Findings and Recommendations

Table 3.2 lists the 17 evaluations undertaken to date under EU management. Their findings and recommendations are presented in this chapter in three sections, one for each of the three types of budget support provided by the EU. The focus of the evaluations reflects the objectives of the three types of contracts: high-level strategic objectives requiring a cross-cutting approach for SDG-Cs; sector-level policies, reforms and governance for SRPCs; and transition to recovery, development and democratic governance and societal and state resilience for SRBCs. Correspondingly, the evaluations focused on the role of budget support in contributing to: global policy and governance achievements (SDG-Cs); sector or sub-sector outcomes and sector governance improvements (SRPCs); and consolidation of vital state functions, including the delivery of basic services to the population (SRBCs). The evaluations also differed in scope, with SRPC and SRBC evaluations looking, to a large extent, at EU budget support only; whereas SDG-Cs evaluations systematically considered the budget support being provided by all development partners to the country. SRBCs need to be examined separately from the other type of general budget support (SGC-Cs) because of the particularities of the countries and type of support provided.

The next three sections present evaluation findings related to SDG-Cs, SRPCs, and SRBC evaluation findings. A last section presents an overview of the main recommendations made across all 17 evaluations.

Evaluation Findings: General Budget Support

Eight multi-donor evaluations of general budget support have been undertaken since 2010 (Table 3.2).

These captured the interactions and combined effects of all budget support provided by all development partners in each of the eight countries20The Tunisia evaluation considered only the EU’s budget support programs, which were provided in a joint framework with the African Development Bank and the World Bank. between 1996 and 2015. The countries included six low-income countries (LICs) with very high poverty levels, poor social indicators, deficiencies in their political framework, weaknesses in governance, and high levels of aid dependency (Burkina Faso, Mali, Mozambique, Tanzania, Uganda, and Zambia) and two lower middle-income countries (Ghana, which had high economic growth rates, low poverty, but high aid dependency, and Tunisia, which had higher per capita income and social indicators, very limited aid dependency but relatively high poverty rates and unemployment). The original evaluations contained in-depth analyses of the country contexts.21The evaluations can be found on

https://ec.europa.eu/international-partnerships/strategic-evaluation-reports_en

- 20The Tunisia evaluation considered only the EU’s budget support programs, which were provided in a joint framework with the African Development Bank and the World Bank.

- 21The evaluations can be found on https://ec.europa.eu/international-partnerships/strategic-evaluation-reports_en

Budget Support as a Package of Funds, Technical Assistance, Dialogue and Performance Measurement

The period being evaluated (roughly 2005–2015, although seven of the eight evaluations concentrated on the period 2005–2010) was a period of high and increasing ODA levels, with budget support being the EU’s and multilateral development partners’ preferred aid modality. Overall, budget support provided a significant and predictable source of funding for recipient governments and created fiscal space for them to undertake discretionary expenditure. The scale of budget support in relation to public expenditure was significant in all countries. Budget support annual disbursements represented as much as 25% of public expenditure in Uganda in the first half of the period; 15% of public expenditure in Burkina Faso; more than 10% in Mali, Mozambique and Tanzania; 8% in Ghana; and 6.5% in Zambia. Even in Tunisia, where it represented only 1.4% of public expenditure, budget support was an important source of funding for discretionary expenditure.

The predictability of the amounts of budget support was high, with disbursements close to planned amounts in most cases. This was true even though a lack of mutual accountability triggered temporary suspensions of budget support by the EU and other development partners in five of the eight countries during the evaluation period. In three cases, temporary suspension was linked to the government’s breach of principles (major corruption and fraud cases had been brought to light in Tanzania in 2007 and 2008; Zambia in 2009; and Mozambique in 2009, 2011, and 2012). At the time, the EU’s general budget support was not yet linked to respect for fundamental values, but only to the eligibility criteria, which continued to be satisfied. While corrective measures were discussed and then implemented, the EU continued to disburse funds, which eased the effect of these suspensions on the government’s Treasury tensions. In the two other cases, Uganda (2012) and Ghana (2013 and 2014), underperformance on results, a deteriorating macroeconomic situation and serious concerns regarding PFM triggered all development partners, including the EU, to suspend budget support since the key conditions were no longer being met.

With these temporary suspensions and deferred disbursements of budget support due to the countries’ breach of mutual accountability, the predictability of disbursement timing could not be maintained: in Mali, Uganda, and Zambia public expenditure was delayed and the government had to seek temporary domestic borrowing.

In almost all EU budget support, capacity development complements funding, policy dialogue, and performance monitoring. Technical assistance is used to strengthen the country’s policy and PFM systems, to improve the accountability of the government toward its citizens, and to strengthen key institutions and policy-making processes. Typical areas of support include external oversight, monitoring and evaluation, underlying statistical data systems and processes, PFM, including gender budgeting and monitoring, and the active engagement of stakeholders in policy design, implementation and monitoring.

Technical assistance usefully complemented budget support in backing governance reforms and reinforcing capacities in PFM, audit, and statistics in six of the eight countries. Where sector budget support was provided alongside general budget support, sector capacities (e.g., in health, water, and sanitation) also benefited from technical assistance. In Ghana, major efforts were made to strengthen the capacities of civil society organizations and to enhance their role in policy processes. Overall, technical assistance remained a minor component of the budget support package and in many instances, evaluators estimated that more could have been done with better planning and a more flexible response to strengthen capacities at the subnational level where policy implementation takes place.

In every result identified in all eight evaluations as a direct or indirect effect of budget support, policy dialogue featured as a central element. Dialogue related to budget support was invariably a crucial factor in improving policies, governance, and policy decision making. Through their policy dialogue, development partners were able to put and keep specific issues on the government’s priority agenda, draw attention to governance matters, and propose and discuss policy options. The development partners also used performance monitoring and the variable tranche indicators to discuss results of policy implementation, corrective measures, and implementation challenges.

The effectiveness of policy dialogue was helped by the strong coordination of budget support donors within a structured framework (Box 3.1). This facilitated harmonization, alignment, and the delivery of joint messages. During the period, temporary suspensions of budget support disbursements led to a severe deterioration of government–development partner relations in five countries. The overall positive assessment of budget support policy dialogue was tempered in several cases by a perceived lack of government ownership and leadership of the policy dialogue (this was not the case in Ghana) as well as by extending budget support areas of interest to ever wider governance and sector issues for which reform capacities were insufficient.

Box 3.1. Development Partner Harmonization and Alignment

All countries had strong formal budget support management structures and national monitoring frameworks. Budget support was managed in a harmonized manner despite the differences in the design and management of each development partner’s budget support. During the periods evaluated, the number of active development partners in both general and sector budget support provision ranged from three (where there was only general budget support) to 19 (in Mozambique). Sector budget support was mostly directed toward social service delivery (health, education, roads, water and sanitation), technical and vocational training (Tunisia), PFM (Mali and Zambia) and decentralization (Zambia). These management structures helped align the development partners with government policy priorities and with the use of national monitoring frameworks and systems and common delivery mechanisms. Their use considerably reduced transaction costs, making budget support a more efficient modality than projects or basket funds.22Basket funds typically pool funds from different development partners into a single time-framed fund, in an autonomous account, with its own management, accounting, monitoring and accountability mechanisms under an agreed set of operating procedures. Funds are most often earmarked for specific uses, prioritised by common agreement between the recipient government and the development partners. See the list of co-operation modalities (B04) in the CRS codes in https://www.oecd.org/development/financing-sustainable-development/development-finance-standards/dacandcrscodelists.htm.EU budget support variable tranche triggers were drawn from these common performance assessment frameworks.

- 22Basket funds typically pool funds from different development partners into a single time-framed fund, in an autonomous account, with its own management, accounting, monitoring and accountability mechanisms under an agreed set of operating procedures. Funds are most often earmarked for specific uses, prioritised by common agreement between the recipient government and the development partners. See the list of co-operation modalities (B04) in the CRS codes in https://www.oecd.org/development/financing-sustainable-development/development-finance-standards/dacandcrscodelists.htm.

Budget Support Contributions to Improving Public Governance

General budget support was found to have induced and sometimes been instrumental in triggering positive and mostly lasting changes in four main areas: policy formulation and implementation, the composition of public spending, public finance management (PFM), and transparency and external oversight.

General budget support accompanied improvement in policies in several areas, depending on the objectives pursued and the weaknesses to be addressed. For example, budget support’s focus on outcomes was instrumental in improving policy monitoring in Uganda and in institutionalizing government annual performance reports. These monitoring reports provided timely information to policy makers and implementers on previous performance and challenges, and thus significantly improved policy making. Strong gains were made in the water and sanitation sector, where policy processes and the quality of policies gradually improved, thanks to the consultative processes nourished by these performance assessments. In other sectors, data reliability did not improve, and policy changes remained based on uninformed political decision making. In Tunisia, budget support contributed to discrete improvements in specific areas of reform, including trade tariffs, business environment regulations, and the tax system.

Improvements in sector policies and delivery processes were particularly substantial when general budget support was paired with sector budget support. In several countries, budget support contributed to the strengthening of sector policies, the adoption of a sector-wide approach and the implementation of sector policies, e.g., for the health and water and sanitation sectors in Burkina Faso. However, sometimes the contributions of budget support were positive but insufficient, by themselves, to improve service delivery. This was the case in Ghana, where budget support played a positive role in improving policy formulation, enhancing intrasectoral coordination (in environment and decentralization), and in strengthening the capacities of key public institutions. It also improved legislation and tariff adjustments designed to benefit natural resource management. However, while budget support helped to maintain the pace of reform and improve the quality of policies in Ghana, it could not overcome the barriers to effective policy implementation.

In the six LICs, the discretionary funding enabled by budget support helped governments to significantly increase their social and pro-poor expenditure (health, education, social protection, water and sanitation, roads, and agriculture).

- In Mali, budget support provision was associated with an increase in expenditure on priority sectors from 39% of total public expenditure in 2003 to 54% in 2009.

- In Uganda, a trebling of poverty reduction expenditure was facilitated at the beginning of the 2004–2013 period when budget support funds came onstream. Budget support made it possible for these expenditures to remain protected from budget cuts during the entire period, but their importance in per capita terms fell drastically after 2004–2005 as the government’s priority spending turned to infrastructure and defence, and basic service expansion stalled.

- Even in countries where priority sectors already absorbed the largest share of public spending, this trend was clearly visible. In Mozambique, for example, the share of public expenditure on priority sectors rose from 61% to 67% during 2005–2012. This increase in spending would not have been possible without budget support.

- In Ghana, the government ring-fenced budget support funding for pro-poor sectors, private sector development, natural resources, energy and oil. Despite this, pro-poor spending and public investment decreased in relative terms over the evaluation period.

In the LICs and Ghana, additional funding benefited spending on wages (higher salaries and more health staff and teachers), non-salary recurrent expenditure (mainly in Ghana), and a higher share of domestic funding of public investments. In addition, the implementation of PFM reform programs improved domestic revenue mobilization in all countries except Uganda and Burkina Faso and was associated with stronger budget planning and budget execution capacity (see below), thus increasing the efficiency of spending and providing an additional window of opportunity to increase amounts available for discretionary expenditure.

In turn, greater expenditure in social and priority sectors expanded access and delivery of services in these sectors. In education, the number of schools, teachers, and textbooks increased; in health infrastructure, essential drugs availability and personnel improved; and in water services, access was expanded. In all countries, budget support directly contributed to an increased provision of health, education, and other basic services.

In all countries, except Burkina Faso (Box 3.2), PFM vastly improved, as evidenced by repeated Public Expenditure and Financial Accountability (PEFA)23The Public Expenditure and Financial Accountability (PEFA) program was launched in 2001 by seven international development partners: The European Commission, International Monetary Fund, World Bank, and the governments of France, Norway, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom. See https://www.pefa.org/. assessments. Budget support played an important role in these improvements through the provision of technical assistance (on issues such as integrated financial information systems, budget management, audit, and the legislative framework), the monitoring of the performance indicators contained in the performance assessments frameworks and in the variable tranches, and the close attention paid to PFM in policy dialogue. In most countries (Box 3.3), budget support was linked to wide PFM improvements at both central and local government levels, except in Tunisia, where the focus on PFM was limited to support for the development of the medium-term expenditure framework. In exceptional cases, such as Ghana, progress in PFM reforms was real but very limited: technical assistance and dialogue brought PFM issues to the fore and contributed to legislative improvements but remained largely ineffective as they were not backed by a prioritized and sequenced reform strategy. Since the reforms applied to only part of the budget, the limited progress made did little to improve the general management of government finances.

Box 3.2. Missed Opportunity to Improve Public Financial Management in Burkina Faso

In Burkina Faso, the PFM priority during 2009–2014 was the introduction of medium-term expenditure planning, and its associated budget program approach; some limited measures for improving budget execution (procurement and procurement control, simplification of expenditure chain); and the first attempts in favour of fiscal deconcentration (the delegation of some fiscal functions from the ministry of finance to line ministries or to sub-national administrative levels) and decentralization (the transfer of responsibility for revenue collection and expenditure management to sub-national levels of government). The role of budget support providers in these endeavours was very muted: they monitored developments, shared their concerns and recommendations with the government, and were occasionally solicited by the government to provide expertise for specific tasks. The slow progress of PFM reforms was not sanctioned by the development partners, who remained almost at the periphery of PFM efforts, possibly recognizing that many other priority issues needed to be addressed (notably the weakness of existing policies and corruption) for PFM reforms to improve expenditure effectiveness.

PFM = public financial management

Box 3.3: Technical Assistance for Public Financial Management in Uganda

Over the period 2004–2013, PFM in Uganda made huge strides at both central and local government levels, gains that were strongly associated with budget support, which helped catalyze these changes. Budget support brought substantial technical assistance, capacity building activities, and analytical services, which both strengthened PFM systems and provided budget support donors with leverage to push PFM issues in policy dialogue. A specific technical assistance support unit facilitated a coordinated effort, the production of common analytical materials (such as the relationship between fiscal decentralization, fiscal incentives, and decentralized services), and the common development and monitoring of PFM indicators and actions. Without budget support funding flowing through domestic PFM systems and the attention focused by development partners on PFM improvements, progress in PFM reforms would have been more limited.

PFM = public financial management

Contributions to Transparency and External Oversight were also made by budget support. Although they recognized the effectiveness of budget support, many EU Member States returned to project aid after 2010 (mainly because their constituents questioned the value of budget support). However, Member States entrust the European Commission to continue implementing budget support as the most effective way of promoting systemic changes, sustainable results, and domestic accountability. They are working closely with the European Commission in policy dialogue, capacity development, and performance monitoring, often through joint actions. To ensure the accountability of its actions to European taxpayers, the European Commission added budget transparency and external oversight as the fourth criterion for budget support eligibility. Within its budget support operations, the European Union prioritizes support for strengthening the functioning of supreme audit institutions (SAIs) and encourages the publication of budgets and budget accounts in a timely fashion. It also supports civil society participation in external oversight through the strengthening of the capacity of parliamentary committees and research bodies to scrutinize the budget. It also supports grassroots initiatives to enable populations to hold a government accountable for its spending actions (both budget management and service delivery).

In the two LMICs, budget support did not specifically target improved public accountability. In the six LICs, the evaluations confirmed that the EU’s dynamic approach to transparency and oversight had paid off, often paving the way for improved governance over the periods considered (all before 2015). Transparency and external oversight improved, as did the control of corruption in a range of countries: Mozambique (improved budget documentation and legislative and institutional framework for the control of corruption); Tanzania (quality, timeliness and scope of audits, external scrutiny and the legal framework for corruption); Zambia (external auditing); Burkina Faso (external oversight, Box 3.2); Uganda (legal framework and strengthening of capacities of accountability institutions, Box 3.3). In Tanzania, corruption cases prosecuted more than doubled between 2010 and 2014. In all cases, improvements were linked to increased operating budgets for the relevant institutions (facilitated by the additional discretionary funding), technical assistance and increased attention within policy dialogue, all linked to the provision of budget support. In Uganda, it took the temporary suspension of budget support to bring the government’s attention to corruption and governance issues.

Box 3.4: Improvement of External Oversight in Burkina Faso

Before 2014, the role of civil society in external scrutiny of public finance management and of the fight against corruption was strengthened through budget support. External oversight was an important part of the policy dialogue between the group of development partners providing budget support and the government. Discussions took place from the Prime Minister’s Office to the technical level. Several development partners used performance indicators in the areas of external oversight and corruption as triggers for disbursement, reinforcing the significance they placed on these issues. To complement budget support, capacity strengthening support for the SAI, civil society, and other control institutions enabled them to be more effective. Although the dialogue did not produce the anticipated corruption and external oversight laws, the development partners’ initiatives enabled civil society to make progress on other fronts, thus creating an improved environment for external oversight, which facilitated the subsequent adoption of an anticorruption law under the transitional government.

SAI = supreme audit institution.

- 23The Public Expenditure and Financial Accountability (PEFA) program was launched in 2001 by seven international development partners: The European Commission, International Monetary Fund, World Bank, and the governments of France, Norway, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom. See https://www.pefa.org/.

Contributions to Improved Social Outcomes

The main objective of all EU budget support is poverty eradication and inequality reduction. General budget support should be used to support the attainment of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). In most of the eight countries examined in this chapter, the provision of budget support coincided with a period when social indicators significantly improved. Regression analysis found these improvements to have been directly linked to the expanded delivery of key public services as a result of increased social and pro-poor spending. Budget support contributed, sometimes very significantly, to this higher spending. Improved outcomes were achieved in education (higher enrolment rates in primary education, higher transition rates from primary to secondary schools, and lower drop-out and repetition rates) and in health (greater use of health facilities, higher immunization rates, lower child and maternal mortality indicators, and lower incidence of diseases).

The gains were momentous, but not always equitable. Generally speaking, rural areas have lagged behind, regional differences have remained widespread, and gains in access have not always been accompanied by better quality of services. For example, greater education access was achieved in Ghana, Tunisia, and Zambia (Box 3.5), but the quality did not follow suit. In Burkina Faso, access to basic services such as education, health, and water and sanitation improved but their quality and infrastructure remained poor. In addition, in some countries, including Ghana and Uganda, the government’s fiscal position strongly deteriorated at the end of the evaluated period and the lack of resources for non-salary recurrent expenditures and investments have seriously weakened the service delivery systems. Finally, service delivery at local government level has not always received adequate attention.

Box 3.5. Expansion of Coverage of Key Social Services in Zambia

The evaluation of budget support in Zambia noted that, in the education sector: “The budget increases have enabled the Ministry to invest more in teachers, classrooms and books. The number of basic schools increased from 7,600 in 2005 to 8,400 in 2010, the number of teachers from 50,000 to 63,000 and the number of primary school pupils from 2.9 million to 3.4 million. The enrolment of girls improved and gender parity was almost achieved at the lower and middle basic levels. The number of Grade 9 examination candidates increased from 190,000 in 2005 to 280,000 in 2010 (with an increase of female candidates from 89,000 to 133,000). Partly as a result of a lack of resources, the quality of education remained low. However, it must be noted that improved access among underprivileged groups changed the composition of classrooms in primary schools, which had an impact on average examination results.” (page 18, Synthesis report).

Contributions to Higher Economic Growth and Reductions in Income and Non-Income Poverty

In Tunisia, the reforms supported by budget support contributed directly to the country’s opening to international trade and coincided with a period of economic growth and stability. Budget support contributed to tax reforms and tariff dismantling as well as to the improvement of economic governance and the business environment, which was essential to improve Tunisia’s international competitiveness (Box 3.6). It clearly also contributed to the Tunisian government’s wider strategic agenda.

Box 3.6. Contribution of Budget Support to the Liberalization of the Tunisian Economy

Budget support in Tunisia supported a set of reforms aimed at liberalizing the domestic market, strengthening the competitiveness of the economy, reform secondary and technical education with a view to reduce youth unemployment. During the period of budget support, macroeconomic growth accelerated, the trade volume with the EU more than doubled in real terms between 1995 and 2006, the trade deficit decreased to near zero by 2008, private investment grew an average by 7.5% a year, labour productivity increased, and the number of apprentices in vocational training and higher education graduates increased dramatically, although they could only partially be absorbed in the labor market where high levels of unemployment persisted.

In the other seven countries, budget support represented a significant share of public expenditure. In tandem with support provided by the IMF, budget support was instrumental in providing essential resources for the maintenance of macroeconomic stability, strengthening the capacity to manage external shocks, and to ensure high economic growth rates. The evaluations confirmed that the eight countries had improved their macroeconomic performance, attaining generally higher growth rates than neighbouring countries that did not receive budget support (although Ghana’s performance declined strongly over the evaluation period). The main reasons for these positive trends were the governments’ overall prudent macroeconomic management and national and sector policies, as well as a number of favourable external factors, including debt relief. Within this conducive context, budget support helped stabilize the fiscal deficit and allowed higher spending without governments having to tap into domestic savings. This spending was often used for public investments, including public infrastructure, helping to stimulate domestic activity and productivity. 24In Mali, budget support was used at the beginning of the period to reduces domestic debt and thus had a direct impact upon economic activity.In Ghana, when development partners stopped providing budget support in 2013–2014 this was an important factor in the government’s decision to accept an IMF stabilization program.

Macroeconomic gains were particularly strong in countries that successfully managed to raise domestic revenues (a priority concern for the EU) and to increase social expenditure. Apart from Uganda, in all of the countries evaluated, domestic revenue mobilization (DRM) increased during the periods of EU budget support. By contrast, in Uganda DRM remained low, and, at the end of the evaluated period (i.e., after 2010) when budget support contributions declined, the government was unable to provide sufficient funding for public services and could no longer sustain social services. The Uganda evaluation suggested that the sheer volumes of budget support received probably crowded out local revenue mobilization. With a low DRM, the sustainability of gains was seriously compromised. In Mozambique and Tanzania, extensive revenue reforms to trigger higher DRM were implemented during periods of budget support provision.

With the improvement of social performance indicators, non-income poverty also decreased significantly in all eight countries over the period. The Human Development Index increased by 11%–14% between 2004 and 2010 in Mali, Mozambique, Tanzania, and Zambia. The period of budget support coincided with a sharp drop in poverty rates in some countries. Significant reductions in income poverty were achieved in Mali (from 61% of the population in 2000 to 51% in 2005) and Ghana (from 17% in 2006 to 8% in 2013). Moderate poverty reduction was seen in Tanzania and Mozambique, but reductions were limited to the cities in Zambia.

The contribution of budget support to these improvements is not quantifiable and none of the gains made can be directly attributable to budget support. However, most evaluations found indirect positive links between budget support and poverty reduction.

- 24In Mali, budget support was used at the beginning of the period to reduces domestic debt and thus had a direct impact upon economic activity.

Evaluation Findings: Sector Budget Support

While sector reform performance contracts (SRPCs) share the general objectives of budget support, they focus more narrowly on supporting sector policies and re¬forms and on improving governance and service delivery in a specific sector or in a set of closely interlinked sectors. In line with the Sustainable Development Agenda 2030’s pledge not to leave anyone behind, SRPCs emphasize equitable access to, and the quality of, public service delivery, particularly for poor and vulnerable populations, and the promotion of gender equality and children’s rights.

The EU has undertaken six sector budget support evaluations since 2010 in Cambodia, El Salvador, Morocco, Peru, Paraguay, and South Africa. The evaluated periods for each country were different but all fell within the 2000–2017 timeframe. These evaluations covered only EU support, except in Morocco where the evaluation encompassed budget support provided by four multilateral and three bilateral development partners. The number of SRPCs in each country varied widely, from 54 programs in Morocco to two in Cambodia.

The evaluated SRPCs were provided to support poverty reduction, macroeconomic policy implementation, good governance (public administration, PFM, and fiscal reform), social sector policies (education, health, social protection, social development), and sub-sector policies or programs (development of a national quality control system, promotion of the environment and trade, and the fight against drugs).

Policy Dialogue, Technical Assistance, and Performance Measurement

In contrast to general budget support (where funding was essential to the results achieved), in SRPCs, technical assistance, policy dialogue and performance measurement were the main drivers of effectiveness, with funding taking a second, even if strategic, place.

Of the six countries evaluated, Cambodia, El Salvador, Morocco, and South Africa were lower middle-income countries (LMICs), whereas Paraguay and Peru were upper middle-income countries (UMICs). Budget support represented the main, and often the only, aid delivery method for the EU in these countries and the volume of funding remained minor relative to total public funding. As opposed to general budget support, where funds could represent 15% or more of public expenditure, depending on the year considered, the countries considered here were not aid-dependent and SRPCs represented, at most, 0.6% of annual public expenditure.

However, this is not necessarily a general characteristic of SRPCs, but rather a particularity of those in this small sample of LMICs and UMICs. For example, the eight countries considered in the previous section on general budget support also benefited from sector budget support, which was found to be as essential as policy dialogue and technical assistance in contributing to observed results.

In the six cases of sector budget support evaluated, actual disbursements were close to planned disbursements, and SRPCS were more predictable than any other aid modality, both in amounts and in delivery timing. Some in-year unpredictability of timing occurred but it was well-managed by the authorities, leaving government budget and Treasury plans unaffected.