Historical Development and Use of Policy-Based Operations, 2005–2020

Instrument Definition

The mandate of the Caribbean Development Bank (CDB) is to reduce poverty and transform lives by contributing to the sustainable, resilient, and inclusive development of its borrowing member countries (BMCs). Policy-based operations (PBOs) are financing instruments1Inclusive of loans, grants and guaranteesused to incentivize the implementation of country-owned policy reforms and institutional changes aimed at advancing sustainable development goals. The policy-based lending (PBL) instrument, while helping to strengthen the effectiveness of public policy frameworks, provides fast-disbursing budget support to finance priority expenditures, and is disbursed following compliance with agreed policy actions. In a broad sense, therefore, the PBL product is a lending modality that supports the process of good policy making and governance, while reducing transaction costs and providing timely resources to national budgets. PBL is complementary to investment lending as it helps to establish an appropriate enabling environment for enhancing resilience, achieving economic growth, and reducing poverty. It is an important component of CDB’s intervention modalities to enhance development effectiveness and responsiveness to the changing needs of members.

CDB offers four types of PBL:

- macroeconomic,

- sector,

- exogenous shock response, and

- regional public goods.

Macroeconomic PBOs address external and/or internal economic imbalances. Sector PBOs support reforms that help address critical sector issues and strengthen the progress toward overall economic development. Exogenous shock response PBOs provide resources in crisis situations to assist with the fallout from a shock and they can be used to support reforms to enhance resilience. Regional public goods PBOs help to embed the policy and institutional frameworks necessary to advance regional cooperation and integration. PBO guarantees may be used to guarantee a portion of debt service on a borrowing or bond issue by a BMC in support of country-owned policy reforms.

PBL can form an important component of country financing strategies. At the country level, the size of the loan is related to development financing requirements defined in terms of balance of payments, fiscal, sector, or other economic funding needs.

- 1Inclusive of loans, grants and guarantees

Evolution of the Policy Framework

CDB began participating in PBL operations in the late 1980s, with operations to support macroeconomic adjustment executed in collaboration with the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the World Bank, and the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB). These addressed complex development problems, made more acute by the increased frequency of natural disasters and the impacts of climate change, external shocks, relatively low growth and high debt. In 2005, CDB formally introduced PBOs into its lending toolkit, which had traditionally focused on expanding productive infrastructural and institutional capacity. The new instrument was guided by a Board-approved policy paper2Caribbean Development Bank: 2005. Policy Paper: A Framework for Policy Based Lending, BD 72/05,outlining the development challenges in the region; the rationale, definition, and objectives of policy-based lending; design considerations; quality at entry standards; organizational and implementation arrangements; and prudential limits.3The IDB played an advisory role in preparation of the paper.This introduced a more appropriate model to support the type of policy and institutional reforms required to address the structural, social and institutional development challenges being faced, and the far-reaching policy and institutional adjustments required to facilitate stronger development pathways.

Since 2005, CDB has sought to gradually strengthen the PBO instrument and the policy governing its use. This has been guided by five external reviews or evaluations, as well as by internal assessments by staff. Over time, these have revealed scope for improving the administration of PBOs, particularly in their design, supervision, and reporting; and the need to develop more a comprehensive and structured policy framework and guidelines. There has also been internal capacity building in results-based management, country fiscal diagnostics, and debt sustainability analysis.

In 2013, a significant revision to the 2005 framework was undertaken4Caribbean Development Bank. 2013. Policy Paper: Framework for Policy-Based Operations - Revised Paper. BD_72/05 Add. 5to provide greater clarity on the principles, procedures, and guidelines for administering PBOs and to anchor them within CDB’s overall risk management and control framework. The changes included:(i) broadening PBOs beyond loans to include grants and guarantees; (ii) clarifying the rationale and purpose for the use of PBOs; (iii) establishing guiding principles for donor coordination; (iv) broadening the types of PBOs to include sector, exogenous shock response, and public goods PBOs, and multitranche, single-tranche and programmatic5A programmatic PBL is a series of single-tranche loans designed to support policy and institutional reforms in a medium-term framework. A multitranche PBL is a single loan consisting of two or more tranches.operations; and (v) clarifying how requests for waivers and the deferral of disbursement conditions, partial disbursements, supplementary financing, and revisions of scope should be handled. These were issues that were not addressed in the 2005 policy paper.

The 2013 framework provided for an increase in the PBL limit from 20% of total loans and guarantees outstanding to 30%, and subsequently, subject to further approval, to 33%. It also introduced risk-based and policy-lending allocation limits (from a credit risk, utilization, concentration and capital adequacy standpoint) at the country level that align with, and preserve, the prudential soundness of CDB. Following a comprehensive review of operations and the establishment of a centralized Office of Risk Management (ORM) in May 2013, the PBL limit rose to 33% in December 2015.

In March 2020, the Board gave approval to an increase in the prudential limit to 38%, creating headroom for lending in response to the fallout from the coronavirus disease (COVID) pandemic. This is expected to be temporary, with a return to 33% by the end of 2023. The move has enabled support to the Bahamas ($40 million) and Saint Lucia ($30 million), with the expectation of lending for economic recovery and resilience to additional pandemic-affected BMCs.

- 2Caribbean Development Bank: 2005. Policy Paper: A Framework for Policy Based Lending, BD 72/05

- 3The IDB played an advisory role in preparation of the paper.

- 4Caribbean Development Bank. 2013. Policy Paper: Framework for Policy-Based Operations - Revised Paper. BD_72/05 Add. 5

- 5A programmatic PBL is a series of single-tranche loans designed to support policy and institutional reforms in a medium-term framework. A multitranche PBL is a single loan consisting of two or more tranches.

Cooperation with Development Partners

The PBL framework encourages collaboration with development partners when they have PBOs that pursue similar expected outcomes to those of CDB. CDB seeks to harmonize appraisal, supervision and monitoring around a common policy matrix. In circumstances where CDB resources will not be sufficient to close the financing gap, staff will either appraise a PBO request as part of a joint operation with other development partners or consult closely with strategic partners to help mobilize resources. Staff are required to assess the adequacy of the macroeconomic framework for the conduct of a PBO. The views of the IMF, the existence of an IMF program, or an Article IV assessment, are important ingredients in the appraisal. In the absence of an IMF program or Article IV assessment in the preceding 18 months, an assessment letter of the macroeconomic framework is requested. In the case of the UK Overseas Territories, a letter of approval from the requisite United Kingdom (UK) authority is sought.

Policy-Based Lending Activity

Over the past 14 years, CDB undertook 27 operations (as of September 2020) amounting to $944.7 million. In 2019, PBL represented 42% of CDB’s total loan approvals and 54% of its loan disbursements. PBL has financed emergency priority spending and helped preserve stability in BMCs, which are highly vulnerable to external shocks and natural disasters. This vulnerability6A CDB working paper argued that its borrowing member countries (BMCs) are, on average, medium to highly vulnerable countries. CDB. 2019. Measuring Vulnerability: A Multidimensional Vulnerability Index for the Caribbean. CDB Working Paper 2109/01. derives from inherent structural characteristics such as lack of economies of scale, export concentration, remoteness from global markets, lack of economic diversification, dependence on external financing, and exposure to natural hazards and climate change. Acevedo Mejia7Sebastian Acevedo Mejia. 2016. Gone with the Wind: Estimating Hurricane Climate Costs in the Caribbean. IMF Working Paper WP/16/199. Washington, DC: IMF. notes that Caribbean countries are seven times more likely than other countries to be affected by a natural hazard, and to suffer damage that is six times greater.

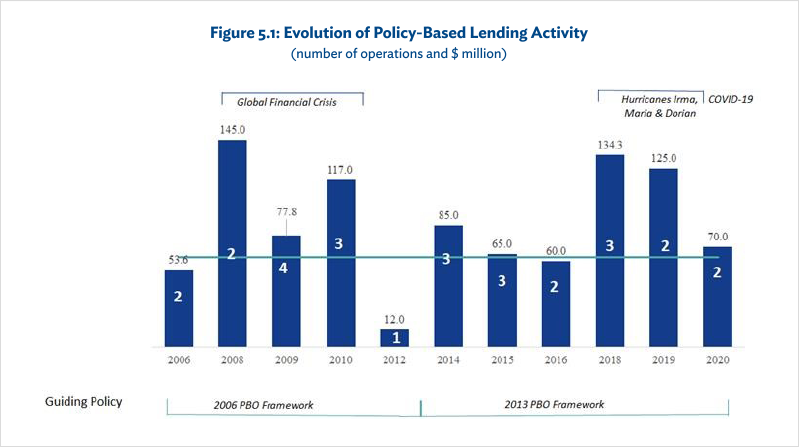

CDB’s PBL activity can be separated into two distinct periods. The first generation of lending was prepared under the original 2005 policy framework. PBL activity rose sharply in 2008–2010 coinciding with the adverse social and economic fallout from the global financial crisis of 2007–2010. Multitranche PBL provided urgently needed financing, supported the restoration of macroeconomic and fiscal stability, and strengthened debt dynamics in the wake of the crisis. The second generation of PBL operations was based on the revised policy framework introduced in 2013, with a high proportion being crisis-response PBL.

During the period 2006–2020,8Data for the year 2020 cover the months January–September. PBL activity correlated closely with periods of economic and natural hazard shocks (Figure 5.1). CDB approved nine PBOs totaling approximately $340 million (36% of the PBL portfolio) on the heels of the global financial crisis in 2008. Given the increasing frequency and intensity of hurricanes in the region, PBL demand has remained strong since 2015, peaking in the 2017 and 2019 hurricane seasons. The extensive damage from hurricanes Irma and Maria to Dominica and Anguilla in 2017 contributed, in part, to some of the PBL lending in 2018. CDB also supported the government of Bahamas in 2019 with an exogenous shock response programmatic PBL ($50 million) to address the fallout related to Hurricane Dorian.

COVID = coronavirus disease, PBO = policy-based operations.

Source: Caribbean Development Bank.

CDB’s ordinary capital resources (OCR) provide 86% of the resources for PBL, with concessionary resources from the Special Development Fund (SDF) (Unified) providing 10% and Ordinary Special Funds 4%. Lending rates and tenors for concessional resources have been determined differently for different country groups, according to levels of gross domestic product (GDP) per capita. Higher lending rates combined with shorter tenors and therefore lower degrees of concessionality have been targeted at higher-income countries which have traditionally had greater market access for financing. Conversely, lower-income countries have accessed SDF resources blended with OCR for greater concessionality of lending.

- 6A CDB working paper argued that its borrowing member countries (BMCs) are, on average, medium to highly vulnerable countries. CDB. 2019. Measuring Vulnerability: A Multidimensional Vulnerability Index for the Caribbean. CDB Working Paper 2109/01.https://www.caribank.org/publications-and-resources/resource-library/working-papers/measuring-vulnerability-multidimensional-vulnerability-index-caribbean

- 7Sebastian Acevedo Mejia. 2016. Gone with the Wind: Estimating Hurricane Climate Costs in the Caribbean. IMF Working Paper WP/16/199. Washington, DC: IMF.

- 8Data for the year 2020 cover the months January–September.

Borrowers and Beneficiaries

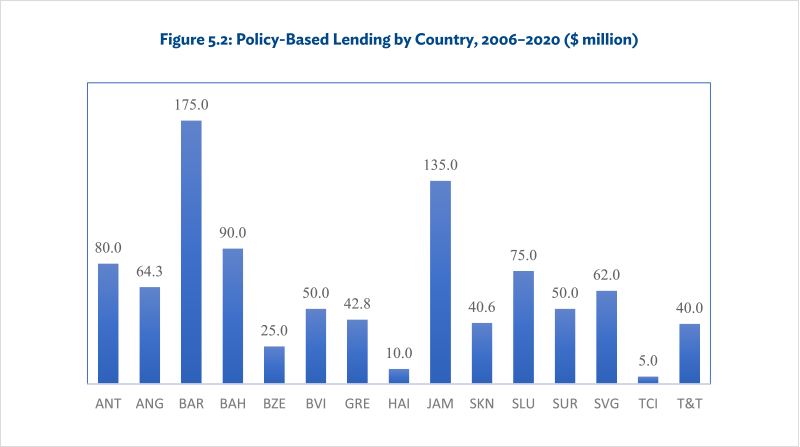

The largest beneficiaries of PBO lending have been the smaller and less developed members of CDB, in keeping with its charter. Approximately 53% of PBL ($454.1 million) was disbursed to smaller and less developed BMCs, with the remaining 47% allocated to more developed BMCs (Barbados, Jamaica, Bahamas, and Trinidad and Tobago). The single largest country beneficiaries were Barbados, with accumulated borrowing of $175 million, and Jamaica, with $135 million (Figure 5.2). Barbados received three PBO operations (in 2010, 2018 and 2019), while Jamaica received two (in 2008 and 2012). PBOs are supported by policy dialogue with the country and, if necessary, technical assistance (TA) to address bottlenecks in implementation and delays in disbursement.

ANG = Anguilla, ANT = Antigua and Barbuda, BAH = The Bahamas, BAR = Barbados, BZE = Belize, BVI = British Virgin Islands, GRE = Grenada, HAI = Haiti, JAM = Jamaica, SKN = St Kitts and Nevis, SLU = Saint Lucia,SUR = Suriname, SVG = St. Vincent and the Grenadines, TCI = Turks and Caicos Islands, T&T= Trinidad and Tobago.

Source: Caribbean Development Bank

Macroeconomic Policy-Based Operations

Macroeconomic PBOs represent the largest proportion (59%) of the CDB policy-based lending portfolio. They are intended to combat the low and volatile growth, fiscal imbalances, and high debt in many BMCs (Table 4.1). During 2010–2019, economic performance in the region, although positive, was slower than the global average and lagged significantly behind that of other small island developing states. During this time, real gross domestic product (GDP) growth averaged 1.5% per annum compared with 4% in other small states. Meanwhile, the average debt to GDP ratio in the region remained high and averaged 63% of GDP at the end of 2019, above the 60% sustainability threshold recommended by many economists.

Table 5.1: Types of Policy-Based Operations, 2006–2020

|

Type |

Number of Operations |

Amount ($ million) |

Percentage of Portfolio |

Country |

Year of Approval |

|

Macroeconomic |

15

|

557.8 |

59% |

BZE, SKN, SLU, ANT, GRE, SVG, ANG, BVI, BAR, BAH, JAM, TCI, TT |

All PBO years |

|

Sector |

4 |

177 |

19% |

SVG, T&T, ANT, SUR |

2010, 2014, 2015, 2016 |

|

Exogenous shock response |

4 |

179.3 |

19% |

ANG, BVI, BAH, SLU |

2018, 2018, 2019, 2020 |

|

Guarantee |

2 |

20.6 |

2% |

SKN |

2006, 2012 |

|

Grant |

1 |

10 |

1% |

HAI |

2009 |

ANG = Anguilla, ANT = Antigua and Barbuda, BAH = The Bahamas, BAR = Barbados, BZE = Belize, BVI = British Virgin Islands, GRE = Grenada, HAI = Haiti, JAM = Jamaica, PBO = policy-based operation, SKN = St Kitts and Nevis, SLU = Saint Lucia, SUR = Surinam, SVG = St. Vincent and the Grenadines, TCI = Turks and Caicos Islands, T&T= Trinidad and Tobago, VI = Virgin Islands.

Source: Caribbean Development Bank.

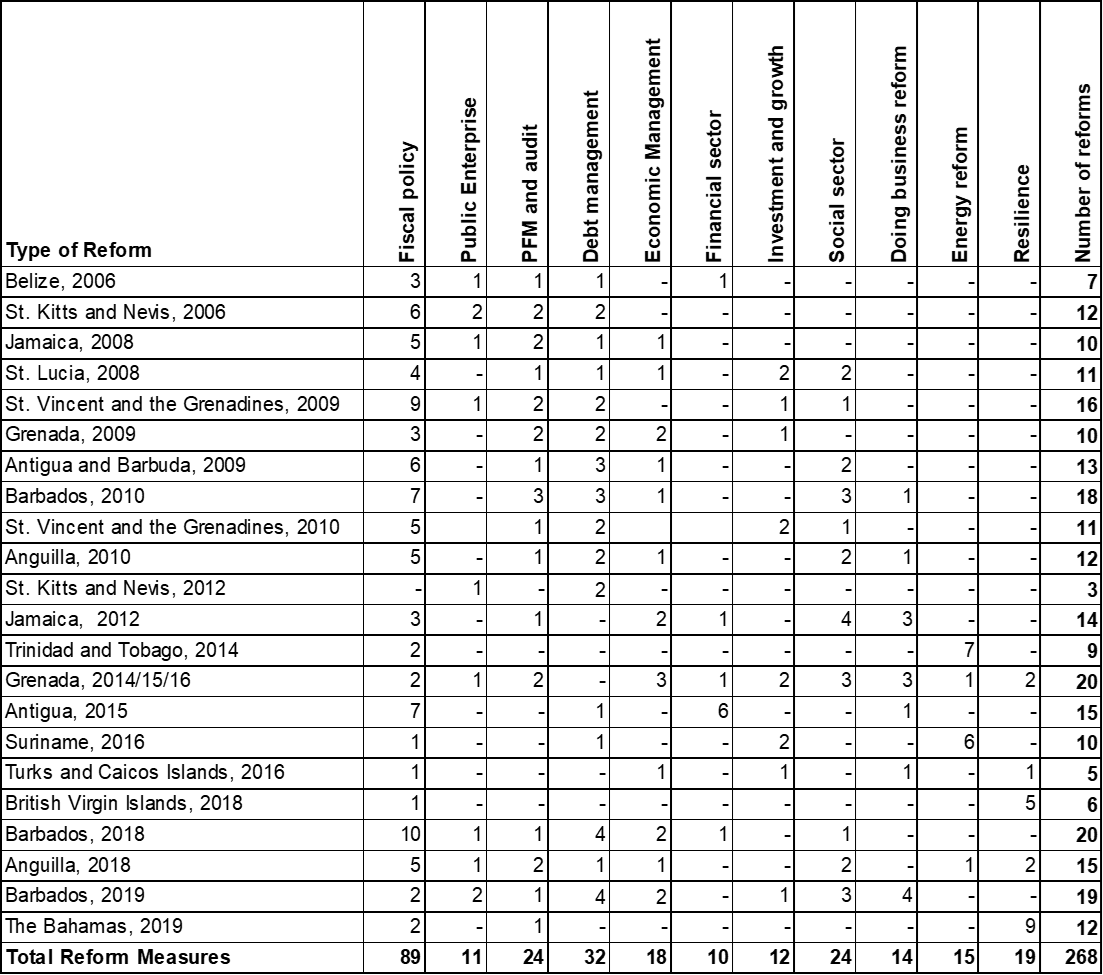

PBL was mainly geared toward fostering macroeconomic stability, reducing rising debt levels, and resolving internal imbalances. The reform milestones were particularly concentrated on fiscal policy in the areas of revenue and expenditure and supported by important institutional reforms to strengthen the framework for revenue collection and the management of state-owned enterprises. Examples of institutional reforms include: the implementation and strengthening of value-added tax (VAT) legislation, introduction of the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) automated system for customs data (ASYCUDA), and reviews of state-owned enterprise tariffs and fees.

Macroeconomic PBL also focused on public financial management (PFM) and audit and improved debt management. The public financial management and audit reforms were geared toward strengthening PFM and audit legislation, conducting public sector institutional assessments and expenditure reviews, supporting the transition from cash to accrual accounting, and improving government financial information government systems, among others.

The efforts to improve debt management and processes focused on milestones that aimed to reduce the stock of arrears and avoid new arrears, introduce debt management strategies, establish debt units, put in place debt advisory committees, and review institutional debt management frameworks.

Exogenous Shock Response Policy-Based Operations

From 2017-2020 there was a sharp increase in the number and size of exogenous shock response PBOs to address the adverse impacts of natural hazard events. The exogenous shock response PBL is intended to ensure that economic and social gains from the country’s reform program are protected as the country recovers from a crisis. In addition, the instrument seeks to ensure that macroeconomic stability is maintained, and long-term fiscal and debt sustainability is preserved. Hence, some of the reforms in exogenous shock response PBOs focus on establishing a sound macroeconomic framework prior to the crisis. The first exogenous shock response PBO was approved in 2018 in the aftermath of hurricanes Irma and Maria.

The reform agendas supported by the exogenous shock response PBOs have broadly resembled those of the macroeconomic PBOs but have also included reforms concerned with disaster management and resilience building. Some of the key reforms supported in the four exogenous shock response PBOs thus far have focused on disaster risk insurance (in the case of Anguilla, Bahamas, and the Virgin Islands) as well as the legislative and institutional framework for disaster planning and response. Reforms connected with social protection and social resilience were evident in the PBL to Saint Lucia (in response to COVID-19), and in the PBOs to the British Virgin Islands and Anguilla. For example, the Saint Lucia PBO supported proxy means testing to improve targeting of poor households so social assistance for immediate COVID-19 relief could be scaled up. As for the macroeconomic PBOs, debt sustainability is an important consideration in the appraisal of an exogenous shock response PBO. This is evident in the PBOs for Anguilla, The Bahamas, and Saint Lucia, where the instrument incentivized primary balance targets, revenue and expenditure reforms as well as policy frameworks such as fiscal rules (Saint Lucia).

Sector Policy-Based Operations

Sectoral interventions have focused primarily on the financial and energy sectors. In the financial sector, the 2015 PBO to Antigua and Barbuda supported a resolution of ABI Bank in order to avoid a disorderly adjustment, which would probably have had severe economic and social repercussions. A disorderly resolution in Antigua and Barbuda would have had an impact on other Eastern Caribbean Central Bank (ECCB) member countries, with possible runs on banks in the currency union, and adverse consequences for their capital base and capital adequacy.

The PBO therefore supported the decision of the Eastern Caribbean Currency Union Monetary Council to try to achieve a resolution of the bank, along with reforms to the banking system and a new Banking Act, 2015. It also included reform actions on fiscal and debt sustainability to help stabilize the macroeconomic situation.

Energy sector PBOs in Trinidad and Tobago and Suriname supported key reforms such as reducing fuel subsidies and CO2 emissions and strengthening the regulatory framework in power generation and renewable energy. It should be noted that sectoral reforms have not been restricted to sector PBOs; in a number of macroeconomic PBOs, specific pillars have focused on pertinent sectoral issues in areas such as doing business and trade facilitation.

Evaluations of Policy-Based Lending

There have been five reviews of policy-based lending (PBL) at CDB since use of the instrument was approved by its Board in late 2005.Three occurred between 2010 and 2012, before CDB had a fully independent evaluation function, with each review being conducted by an individual expert. The Office of Independent Evaluation (OIE), which was created in 2012, then oversaw a comprehensive PBL evaluation (2006–2016), using a theory-based approach with four in-depth case studies, reporting in December 2017.In the following year, as part of an OIE cluster country strategy and program evaluation (CSPE) of the Organisation of Eastern Caribbean States, a review of PBL experience with relatively small borrowers was undertaken.

Together, the five studies document the evolution in CDB’s guidance for, and practice of, policy-based lending. Two generations of policy-based lending are discernible. The first (2006–2010) was on average characterized by ambitious numbers of prior actions, widely scoped, with a sometimes enuous connection to expected reform outcomes. Delays in implementation and condition waivers were relatively frequent. The second generation (post-2010) featured fewer prior actions with a clearer causal connection to outcomes. There was also a progression from multitranche loans to either single-tranche loans or a programmatic series. The degree of national ownership of prior actions and reform programs tended to increase over the period.

The evaluations identified opportunities for continued improvement in CDB’s PBL practice. In particular, CDB could: take a longer view of reform outcome monitoring, not ceasing at loan disbursal but tracking through successive country strategy exercises; document capacity constraints and TA requirements associated with reforms more explicitly; and provide greater analysis of the quality and depth of prior actions at the time of appraisal.

First Assessment of Caribbean Development Bank Policy-Based Lending, March 2010

Background and Terms of Reference

Following CDB’s adoption of the PBL instrument in 2005, multitranche policy-based loans were made to Antigua and Barbuda, Belize, Grenada, Jamaica, St. Kitts and Nevis, St. Lucia, and St. Vincent and the Grenadines over the period 2006–2009, with an approved total of $242.8 million. In 2010 CDB’s Evaluation and Oversight Division9The Evaluation and Oversight Division (EOV) was until 2011 a unit reporting to the Vice President of Operations. A new Evaluation Policy converted it into the Office of Independent Evaluation, reporting to the Board, beginning in 2012commissioned a review of experience with the PBL instrument to date. The overall objective was to assess:

(i)design and inputs, consistency with other operations, validity of underlying assumptions, and whether it addressed the relevant development constraints;

(ii)ownership and the extent to which governments were fully committed to, directly involved in, and accountable for the program of policy reforms;

(iii)conditionalities and the ability of the country to meet loan conditions within the time frame specified

(iv)the effectiveness of monitoring and supervision by CDB;

(v)the effectiveness in achieving the results when there is failure to meet conditionalities;

(vi)the level of consultation and partnership in design and implementation; and

(vii)the role of CDB and the rationale for PBL financing in relation to the activities of the World Bank, the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB), the International Monetary Fund (IMF) or other relevant international financial institutions operating in the BMCs.

The terms of reference did not mention the Development Assistance Committee of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD-DAC) evaluation criteria or require a rating of performance, but rather they focused on lesson learning and recommendations for improved implementation. An individual consultant with a background in public finance, fiscal policy, and banking systems was engaged. The consultant conducted a document review, interviews with Board members and staff, and country visits to meet with senior officials and heads of agencies charged with implementing PBL prior actions.

Review Findings

Context and analytic framework. The review observed that PBOs over the 2006 to 2009 period were transacted in part due to imminent fiscal crisis, and in part out of national political will for a longer-term reform and social protection. The main influencing conditions were:

- the emergence of fiscal pressures as expenditure and debt commitments outstripped revenue by amounts in excess of available financing on prudent terms;

- an assessment that the financing gap was not quickly reversible and that measures being taken to address it would take time to yield results;

- a judgment that financial support already finalized or being discussed with other lenders and donors would not be delivered in time to avert a potential payments crisis; and

- a conviction that a PBL would ease the immediate fiscal pressures, forestall a potential budget crisis, and allow time for the country to implement policies that would provide lasting stability and improved growth potential.

CDB’s analytical basis for its PBL lending at the time, shared by other multilateral development banks (MDBs), recognized the pervasive role of the public sector in economic development in small developing countries, and particularly the way in which government policies affect private behavior, investment, and growth. Since these policies were implemented through the national budget and the activities of government-controlled entities, fiscal policy could have a profound influence on growth and the pace of development.

At the same time, it was recognized that a focus on fiscal policy, public sector management and reform, and debt sustainability, while necessary, was not sufficient to achieve lasting stability and growth, particularly in the 2–3-year timeframes of PBOs. Other factors, including good governance and credible institutions governing law and order and property rights, can be equally important.

Design process. Typically, a cross-sectoral team of CDB staff visited the country in question for one week. It reviewed the economic situation and policies, focusing on public finances, debt, and the government’s program of adjustment and reform. The macro-fiscal framework and projections were developed, often with inputs from the work of other institutions, including the Eastern Caribbean Central Bank (ECCB), the World Bank, the IMF, and other development partners. In addition, TA needs for diagnostic work or program implementation were assessed, taking into account TA from other providers, including the Caribbean Regional Technical Assistance Center (CARTAC).

The review found that staff had collaborated closely with country officials and staff of other MDBs, the IMF, and the ECCB on program design, including the macroeconomic framework; projections over the medium term; debt sustainability analyses; and appropriate policies or actions to be incorporated in PBL conditions. It stated that analytical work on topics relevant to the objectives of the PBOs, such as the impact of debt restructuring and the effects of the global financial crisis had been noteworthy.10CDB’s analytical work on debt dynamics in Jamaica, for example, helped catalyze contributions from the IDB and World Bank in this area.The staff analysis of the likely impact of PBL on poverty and the social sectors was frank and well informed.

All or most of the policy actions included in a loan proposal were expected to have originated from the country’s own economic reform program, with explicit consideration of the likely impact on social conditions and poverty. In cases where other lenders were present (usually the World Bank or IDB) disbursement conditions were to have been calibrated to achieve consistency across institutions and avoid “conditionality arbitrage.”

However, two areas in program design needed attention: (i) the specification of PBL objectives and likely outcomes; and (ii) the treatment of assumptions and macroeconomic projections. Since clarity was essential for program design, conditionality, and monitoring and evaluation, there was a need for a clearer explanation PBL objectives, creating a stronger basis for the assessment of performance. Furthermore, further refinement of the techniques for macroeconomic and fiscal projection, including explanations of the basis for key assumptions and projections, was also needed to sharpen the analysis and bolster the credibility of the PBL instrument.

Conditionality. The review summarized the guidance on conditionality from various CDB documents:

(i) Dialogue with a wide cross-section of country officials was critical to identifying and designing conditions that reflected a strong commitment to reform, and that could be achieved during the implementation phase

(ii) Structural changes and institutional strengthening take time, and a PBL should reflect this. The activities to be undertaken during the disbursement period should be within the implementation capacity of the borrower and should be capable of being monitored

(iii) The conditions and associated activities need to be clearly defined and time-bound

(iv) Conditions should consist only of actions critical for achieving program objectives.

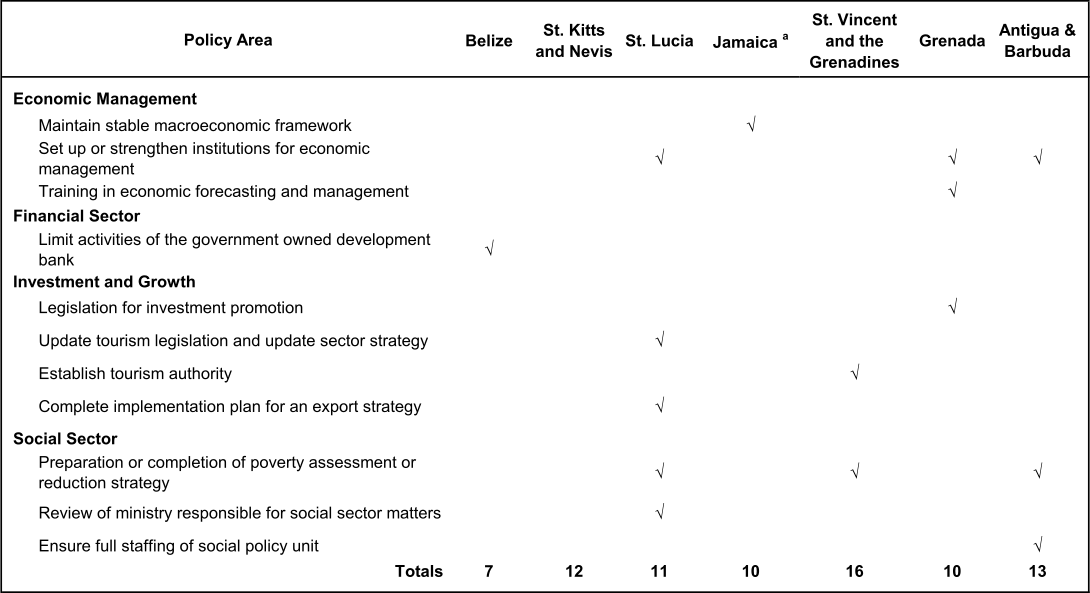

The seven PBOs to 2009 were multitranche operations. Most conditions (about 80%) related to fiscal policy, public financial management (PFM), and debt management, with measures in other areas (economic management, investment and growth, and the social sector) accounting for an average of about 6% each (Table 5.2). Under the fiscal and debt umbrella, most types of conditions were in the revenue category followed by measures covering PFM, debt management, and expenditure.

The average number of conditions for disbursement of the first tranche of PBL operations was 10, with the figure rising from five in the first PBL to Belize in 2006 to 15 in the case of Grenada in 2009. With regard to total conditions (covering first- and second-tranche disbursements), these increased from nine for Belize to an average of 30 for St. Lucia and Grenada, with a pronounced backloading of conditions, particularly in the case of St. Lucia. A large number of conditions were included in some of the PBOs.11By comparison, a $450 million development policy loan by the World Bank to El Salvador for public finance and social sector reform, approved in January 2009, contained a total of 14 disbursement conditions for two tranches.In small countries with limited capacity, the requirements were viewed as overly burdensome.

Table 5.2. Conditions in Caribbean Development Bank Policy-Based Loans, 2006–2009

* First tranche condition only has listed in Board documents

Country performance on conditions. Compliance with first-tranche loan conditions during 2006–2009 was mixed. Three of the six borrowing countries (Belize, Grenada, and St. Vincent and the Grenadines) met all their conditions without waivers, postponements, or adjustments and were able to draw down their first-tranche disbursements within about 2 months of the date of the loan agreement. Jamaica also secured a rapid disbursement after adjustments to its initial policy matrix, in part, to ensure consistency with the conditions of the World Bank’s development policy loan. Of the remaining countries, St. Lucia’s first-tranche disbursement took place following CDB’s agreement to re-program five conditions to the list of second-tranche conditions. In St. Kitts and Nevis, after a delay of more than 1 year from the signing of the loan agreement, the first-tranche disbursement took place following a waiver of one of the conditions.

Observations on loan conditions. An important contribution of the review was to gauge the depth of “ownership” of PBL conditions and reforms, as expressed by senior national officials. Some key messages emerged:

(i) The collaborative manner in which CDB staff arrived at a consensus on loan conditions withnational officials and other MDBs was appreciated

(ii) Loan conditions helped mobilize domestic support for key reforms. However, PBL conditions sometimes incorporated policy commitments which were not yet fully developed, or for which a domesticconsensus had not yet been achieved, which adversely affected ownership

(iii) here was a tendency to overestimate domestic capacity as well as the speed of TA delivery and government processes, including Cabinet decision-making and the drafting and approval of legislation.A smaller number of disbursement conditions would have been preferred. Policy actions requiring TA delivery should have been excluded until the arrangements for the funding and delivery of the TA had been finalized.

(iv) Given uncertainties in reform progression, more flexibility in applying second-tranche conditions was needed.

The evaluator added some summary reflections regarding CDB’s use of conditionality:

(i) Rather than multitranche operations, CDB should consider designing single-tranche PBL, withsubsequent operations and disbursements being consistent with an agreed medium-term strategy (this was later to be called the “programmatic approach”).

(ii) Caution should be exercised when requiring legislation as part of loan conditions. While legislation often needs to be updated or introduced as part of the process of reform, it is important to avoid a drift toward treating legislation alone (or action plans) as substitutes for real progress

(iii) Given the high incidence of poverty and inequality in the Caribbean and the importance of poverty reduction and social progress in CDB’s objectives and strategies, greater efforts should be made to include conditions aimed at achieving social objectives or mitigating adverse effects from adjustment and reform measures.

Monitoring and supervision. Overall, the assessment found that CDB’s procedures for monitoring and supervising its policy-based loans had not kept pace with PBL operations. Procedures were built on pre-existing systems for investment lending and had been insufficiently adapted to the PBL instrument. Reporting by staff to senior levels in CDB was ad hoc. Reporting required of borrowers in loan agreements (on macroeconomic indicators every quarter for 5 years) was viewed by countries as burdensome and therefore not regularly submitted.

Conclusions and Lessons

The review noted that loans had facilitated improvements in frameworks for macroeconomic management, fiscal policy, debt management, and overall public financial administration. Also, revenue systems had been modernized and debt restructuring facilitated. In addition, through their TA components, PBOs had helped strengthen capacity in areas, including macroeconomic forecasting, budgeting, and debt management.

The review observed that PBOs require careful consideration of feasible policy options, and analytical skills that can mold these into credible loan operations. They also require clear objectives and focused conditions, with specific, measurable goals, particularly in PBOs which are part of joint policy support operations with other MDBs. Goals need to be clear, realistic, and modest with greater consultation in setting loan conditions that are few in number and well defined. A series of discrete, well-defined steps toward reform, supported by a single-tranche PBL, might be more effective than a multitranche loan based on a hopeful set of longer-term commitments. A development bank with a commitment to improving social conditions should not shy away from incorporating social sector conditionality in its policy work.

Recommendations

The review offered four main recommendations:

(i) Focus PBL operations on public sector reform or social sector priorities which are not already covered by policy loans from other MDBs.

(ii) Specify the objectives of the PBL more clearly and pursue analytical work that can support improved program design and conditionality.

(iii) Adhere to the principles of parsimony and sharper the focus on disbursement conditions. The requirement for legislation as part of loan conditions should be used sparingly.

(iv) Develop guidelines specific to the monitoring and supervision of PBL.

- 9The Evaluation and Oversight Division (EOV) was until 2011 a unit reporting to the Vice President of Operations. A new Evaluation Policy converted it into the Office of Independent Evaluation, reporting to the Board, beginning in 2012

- 10CDB’s analytical work on debt dynamics in Jamaica, for example, helped catalyze contributions from the IDB and World Bank in this area.

- 11By comparison, a $450 million development policy loan by the World Bank to El Salvador for public finance and social sector reform, approved in January 2009, contained a total of 14 disbursement conditions for two tranches.

Second Assessment of CDB Policy-Based Lending, May 2011

Only one year after the first assessment of policy-based lending, the Evaluation and Oversight Division commissioned a second one. However, rather than review operational experience as had been done previously, this second exercise was tasked with examining CDB’s overall framework for PBL operations, as a prelude to updating it.

The same individual consultant who had performed the first assessment undertook the second, employing the same methodology of document review and key informant interviews, but this time adding a survey.

Terms of Reference

The consultant’s terms of reference were as follows:

(a)Assess the appropriateness of CDB’s framework for PBL, with attention to:

(i) the existing prudential limit of 20% of total loans outstanding,

(ii) the interest rate structure,

(iii)the use of concessional Special Development Fund (SDF) resources to fund this product and adherence to the SDF strategic objectives,

(iv) the scheduling and role of TA in the design of the PBL and in supporting capacity building and institutional strengthening to achieve the desired results of the PBL

(v)the adequacy of institutional arrangements at CDB

(b)Make recommendations for changes, if necessary, to the framework.

Background and Regional Context

By the end of 2010, the global financial crisis was taking firm hold in the Caribbean region:

- Low or negative rates of GDP growth had characterized many of CDB’s BMCs since the early 1990s, and in 2010 the region as a whole was estimated to have registered a contraction.

- A heavy debt burden derived from several years of weak fiscal performance continued to constrain growth and poverty reduction.

- Weak or declining growth had led to rising unemployment, social pressures exacerbated by rising food and fuel prices, and worsening poverty and social indices.

- Growth was projected to be sluggish until tourism could rebound and was therefore anchored in a recovery in the United States and Europe that remained uncertain for 2011–2012.

It was against this backdrop that the demand for policy-based lending was framed, to both stave off fiscal crisis and facilitate growth-oriented reforms.

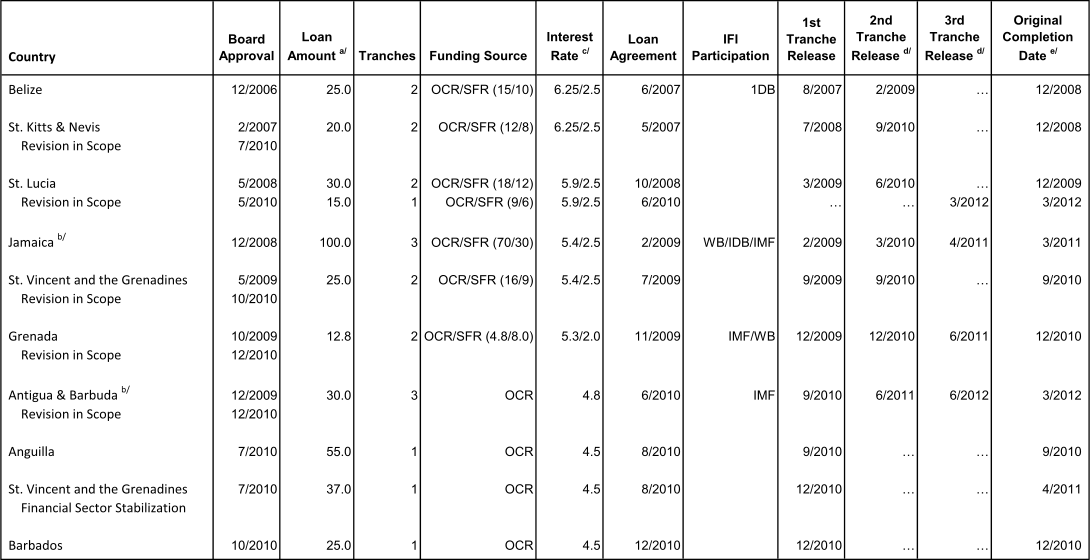

Three new loans had been approved since the previous review, two being single-tranche operations (Table 5.3).

TABLE 5.3: PBLs by the CDB 2006 -2010: Basic Data

Source:CDB

a' In millions of US Dollars

b' Indicates loans composing three equal tranches

c' Two interest rates are quoted. One for OCR one for SFR

d' Actual date or latest estimate

e' Original date by which loan was expected to b fully disbursed. In the case of Jamaica the date refers to the second tranche disbursement

… = not applicable, CDB = Caribbean Development Bank, IDB = Inter-American Development Bank, IFI = international financial institution, IMF = International Monetary Fund, OCR = ordinary capital resources, SFR = Special Funds Resources, WB = World Bank.

Of the 10 PBOs listed in Table 4.3, several experienced delays and performed below expectations. There was an average delay of 6 months between Board approval and the signing of loan agreements. Implementation of loan conditions was delayed because of weak capacity in the BMCs, and unclear objectives and design issues (including, particularly in the earlier PBL operations, an excessive number of conditions in multitranche loans and in situations of rapidly changing economic circumstances). Timely implementation and disbursement were observed in only two of the seven multitranche loans. Disbursements of the remaining five loans were hampered by problems of implementation, with a need for adjustments, waivers, postponements or deferrals, or revisions of scope. By contrast, single-tranche loans were disbursed in a timely manner, without the need for waivers, shortly after finalization of the loan agreements.

Review Findings

Institutional and management arrangements. The review assessed the evolution of CDB’s arrangements to manage PBL and found a number of issues that needed to be addressed:

- The “prudential limit” on policy-based lending of 20% of total loan disbursements had been reached by the end of 2010. CDB either had to severely restrict further lending or raise the limit.

- CDB needed to clarify the role of the IMF and other MDBs if they were to be involved.

- CDB should clarify operating rules for the funding of PBL by OCR or a blend of OCR and concessional resources (a blend of funding should occur only where there was a social sector or poverty reduction component).

- CDB should establish criteria for recommendations to the Board for the approval of waivers, partial disbursements, and revisions of scope.

- Separate and specifically adapted documentation should be prepared for the appraisal, supervision, and review of PBL (rather than relying on existing investment loan procedures).

- The role of CDB in financial sector restructuring needs to be clarified. Experience with bank rescues in two BMCs suggested that restructuring only be done in coordination with other lenders and TA providers.

- Revised guidelines for sectoral PBL operations are needed, including the extent to which, like IDB, CDB plans to develop them to tackle the many challenges in the social sector.

- An appropriate balance needs to be struck between supporting home-grown reforms and undertaking lending operations in which the contribution of CDB is clearly identified.

Conclusions and Recommendations

The review concluded that there was a pressing need for CDB to change its processes given the economic crisis facing the region at the time, and the fact that CDB had reached the 20% PBL lending limit set under the 2005 policy.

After 5 years, important gaps had surfaced in CDB’s framework, indicating that it was no longer adequate to address recent developments in PBL activity or to serve as a comprehensive guide to future PBL operations. There was a need for greater clarity on key aspects, including the review and supervision of PBOs, loan terms, waivers, TA, and the role of partner institutions, such as the IMF and World Bank. Given the uneven performance of PBOs over the first 5 years (as measured by disbursement delays and the incidence of requests for waivers and revisions of scope), the framework needed to be strengthened by updating the policy and operational guidelines.

The review made the following recommendations:

1.Prudential limit and terms

(a)Increase the limit on PBL from 20% to one third of total loans outstanding, with the numerator and denominator measured as a 3-year moving average. Clarify the definition of the limit in the PBL operational guidelines.

(b)Clarify the principles that determine the funding of PBL, and, in particular, the blending of OCR with SDF and OSF.

(c)Apply OCR terms to macro-type PBL operations, and a blend of OCR and concessional funding for PBL operations with a clear poverty-related, social sector, or TA focus.

(d)Given the interest expressed by some BMCs, explore the feasibility of giving borrowers the option of fixed or floating interest rates.12IDB allows borrowers to select one of two interest rate options: (i) a pool-based adjustable lending rate, which is tied to the average cost of a pool of medium- to long-term borrowing, or (ii) a London Interbank Offered Rate (LIBOR)-based lending rate.

2.PBL design and review

(a)Specify, document, and distribute to directors, BMCs, and CDB staff appraisal standards, supervision and management review practices, and evaluation criteria that are specific to PBL operations, including those, such as the recent PBL for Barbados, that are based on an assessment by the CDB of the quality of policies and actions which are fully implemented by BMCs before completion of the appraisal.

(b)Extend the period between loan approval and the signing of the PBL agreement beyond the current maximum limit (60 days) only in cases where the Loans Committee is satisfied that an extension would not result in a substantively changed macroeconomic framework or outlook for the BMC than that discussed at the time of board approval.

(c)Document the procedures and review criteria used by the Loans Committee in the conduct of its assessment and approval of PBL proposals from the staff.

(d)On the completion of each PBL operation, prepare completion reports to facilitate institutional learning and adequate evaluation.

(e)Include a quantitative assessment of the impact of each PBL on the borrower’s debt in the PBL documents sent for approval to the Loans Committee and the Board.

3.Variations of PBL

(a)Since macro-type and sectoral PBL operations were contemplated in the policy approved by CDB’s Board, but no sectoral loan has been developed, clarify the operational differences between macro-type and sectoral PBL, with examples of what would constitute a sectoral PBL, and how such a PBL would be managed—including for operations in the public, financial, and social sectors.

(b)Clarify the policy and practice regarding the role of the IMF, World Bank, and IDB as partners in PBL operations.

4.Waivers, revisions in scope, and disbursements

(a)Incorporate into the PBL guidelines the policies and practices regarding waivers, deferrals, and revisions of scope, including a clarification of the roles of the Board, the President, and the Loans Committee.

(b)Set out guidelines governing partial disbursements and supplementary financing.

(c)Include in the operational guidelines the process for communicating to BMCs CDB’s decisions on tranche disbursements.

5.TA and coordination with other lenders and donors

(a)Revise the guidelines to require: (i) early consultation with other lenders and donors on ongoing and planned PBL operations and related TA issues; and (ii) a summary of these discussions in the appraisal document.

(b)Specify more clearly in loan proposals to the Board an assessment of the TA (if any) needed to achieve the objectives of each PBL, the scheduling and delivery of such TA by institution, and the specific contribution of the CDB, including through TA loans or grants.

- 12IDB allows borrowers to select one of two interest rate options: (i) a pool-based adjustable lending rate, which is tied to the average cost of a pool of medium- to long-term borrowing, or (ii) a London Interbank Offered Rate (LIBOR)-based lending rate.

Third Assessment of Policy-Based Lending, September 2012

Notwithstanding the guardedly positive assessments of the 2010 and 2011 reviews, some CDB Board members still questioned the effectiveness of PBL and the extent to which outputs and outcomes were being achieved. This concern was prompted in part by the waivers sought and granted to certain BMCs, as well as questions about whether the conditions attached to the PBOs had been commensurate with the gravity of the fiscal, debts and broader macroeconomic situations.

Terms of Reference

A study was commissioned, again with an individual expert, with the following terms of reference:

- Review the rationale and considerations underpinning the current policy-based lending framework.

- Assess the effectiveness of CDB’s policy-based interventions (loans and TA) in support of policy reforms and institutional changes in its BMCs.

- Assess the institutional capacity of CDB to design and supervise effective policy-based interventions.

- Identify lessons learned and opportunities for improvement in policy-based operations and recommend other instruments CDB should consider in support of fiscal and debt management in its BMCs if policy-based interventions are not considered the most effective instrument.

The assessment was based on key informant interviews (CDB staff and members of the Board of Directors), a document review, and a comparison between the PBL policies at CDB and those at other MDBs.

Conclusions and Recommendations

The review concluded that there was both demand- and supply-side appetite for further policy-based lending. However, improvements were needed in supervision and monitoring, and questions had been raised as to whether in, certain situations, PBOs had delayed necessary IMF-supported adjustment by BMCs and/or whether the reform agendas as designed and implemented had been sufficiently robust, given the regression that appeared to have occurred in certain cases.

The review recommended that;

(i)The limit on PBL be raised to 33% of loans outstanding (from 20%), with the tenor on individual loans reduced to 10 years (which was a better match with the time period of reform completion).

(ii)The operational guidelines be revised to specify conditions under which the Board could be asked to approve waivers, deferrals, and scope revision of PBL conditions.

(iii)PBL not be offered to borrowing members in the absence of either an IMF Stand-By Arrangement, or an IMF opinion on the adequacy of a “home grown” program of adjustment.More generally, ensure greater collaboration with the IMF, World Bank, and IDB in design, supervision, and monitoring of PBL operations.

Findings

The assessment summarized CDB PBL operations (Table 5.4).

Table 5.4. Summary of Caribbean Development Bank Policy Based Lending Operation

|

Country |

Policy-Based Lending |

Comment |

|---|---|---|

|

Anguilla (2010) |

$55 million (OCR 100%); for debt restructuring |

PBL objectives achieved; strong political commitment via governor of the territory |

|

Antigua and Barbuda (2009) |

$30 million (OCR 100%) in three tranches (one tranche undisbursed at July 2012) |

In progress; high completion rate of conditions; effected in conjunction with IMF Stand-By Arrangement (SBA) |

|

Barbados (2010) |

$25 million (OCR 100%) single tranche to “ease fiscal strain” and protect social gains |

This was an ex post PBL (conditions already fulfilled); no conditions related to foreign exchange outlook given debt profile; rating downgrade in July 2012; concerns remain |

|

Belize (2006) |

$25 million (OCR 60%, SFR 40%) in two tranches to close fiscal financing gap and facilitate debt restructuring |

Policy conditions set by CDB were achieved, but the country has since regressed and another debt restructuring is imminent |

|

Grenada (2009) |

$12.8 million in three (originally two) tranches (OCR 37.5%, SFR 62.5%) to strengthen economic management and social policy frameworks |

In progress at June 2012; most conditions were marked “achieved” with minor delays in some instances, but the fiscal situation has deteriorated; this has been attributed to adverse external factors; waiver granted |

|

Jamaica (2008) |

$100 million (OCR 70%; SFR 30%) in three tranches as part of a program with other MDBs to improve “debt dynamics” and economic management |

Loan conditions were marked “achieved;” however, Jamaica has since regressed and is reportedly engaging with the IMF for a new SBA |

|

St Kitts and Nevis (2006) |

$20 million (OCR 60%, SFR 40%) to improve “debt dynamics” by replacing high-cost debt |

Some reforms achieved, but PBL objectives not fully realized owing to global crisis; full disbursement, although three conditions remain unmet |

|

St Lucia (2008) |

$45 million (OCR 60%, SFR 40%) in three tranches to build institutional capacity and expand fiscal space |

Most conditions not satisfied but in an advanced stage of completion; waivers approved |

|

St Vincent and the Grenadines (2009) |

$25 million in two tranches (OCR 64%, SFR 36%) to preserve fiscal and debt sustainability |

Three conditions outstanding at June 2012 |

|

St Vincent and Grenadines (2010) |

$37 million, single tranche (OCR 100%); sector PBL to restructure and divest the National Commercial Bank of SVG and maintain domestic financial stability |

Conditions achieved |

CDB = Caribbean Development Bank, IMF = International Monetary Fund, MDB = multilateral development bank, OCR = ordinary capital resources, PBL = policy-based lending, SBA = Stand-By Arrangement, SFR = Special Funds Resources, SVG = the Bank of Saint Vincent & the Grenadines was formerly known as the National Commercial Bank (SVG),

Source: CDB, SDF-8 A Framework for the Continuation of Resources to Address Fiscal Distress, Annex, SDF 8/3 –NM-2-1

Review of Policy-Based Lending States of the Organisation of Eastern Caribbean States, 2006–2018

As part of a cluster evaluation of CDB’s country strategies and programs in the Organisation of Eastern Caribbean States (OECS), the Office of Independent Evaluation (OIE) undertook a review of PBL experience in these six countries, and three overseas territories of the United Kingdom. The review drew heavily on the 2017 OIE evaluation of all CDB PBL (presented below) and distinguished between first- and second-generation loans. First-generation loans were characterized by more numerous and diverse prior actions, while second generation loans were more focused on their reform expectations.

The OECS borrowers are among the smallest and most vulnerable of CDB’s members, with some in debt distress and others at moderate to high risk of becoming so. Over the review period, five OECS members received 10 PBL operations totalling $319 million. The loans supported reforms in PFM; public debt restructuring and management; macroeconomic planning; public sector reform; social sector reform; sector reform (banking and finance, tourism, food safety, energy regulation); and trade facilitation.

As with other studies, this review confirmed the demand for the instrument in facilitating debt restructuring and averting banking crises in the Eastern Caribbean Currency Union, as well as in supporting “home-grown” reforms.The review probed some important design issues.Apart from noting the incidence of wide and unfocused reform plans in some early PBOs, it assessed the “quality” of prior actions across all 10 PBOs.

To do this, it applied the IDB classification of low-, medium-, and high-depth prior actions, according to the likelihood a given prior action would trigger lasting policy or institutional change. On this basis it found 25% were low-depth, 48% medium-depth, and 27% high-depth.In programmatic series, high-depth prior actions were observed in the later loans, evidence of good sequencing. As CDB had not at that time undertaken such an explicit analysis of prior action depth, the OES review suggested that it begin doing so.

The review found evidence that PBOs had facilitated bank resolutions in three members following the 2008 financial crisis, heading off potential contagion in the Eastern Caribbean Currency Area.Orderly debt restructuring and avoidance of default had also been accomplished in one of the smaller members.

The outcome of targeted reforms in PFM, public debt management, tourism, trade facilitation, disaster management (legislation, building standards and codes), and social safety nets was documented. However, there were numerous implementation delays across the portfolio, often as a result of insufficiently anticipated gaps in national capacity.

The review made a number of suggestions for improved PBL planning. CDB should:

(i)adopt and apply a conceptual framework for explicit definition of the quality of prior actions;

(ii)improve documentation, for the sake of transparency, of how prior actions were arrived at and the extent to which they are attributable to policy discussion between CDB and the borrower;

(iii)document the needs for TA associated with PBL reforms, and what plans exist for its provision; and

(iv)consider making greater use of PBL to build ex ante resilience, including, for example, fiscal buffers and better physical planning and building codes.

Independent Evaluation of Policy-Based Operations (2006–2016)

This was the first fully independent overall evaluation of CDB PBL, carried out by its Office of Independent Evaluation (OIE). It assessed the nearly $550 million in PBL to 12 borrowing members approved over the period 2006–2016, employing a significantly higher level of effort than the three earlier reviews of 2010–2012.

Objectives of the Evaluation

The evaluation’s objectives as stated in its terms of reference were to assess:

- the need for the PBL program,

- the relevance of the PBL program to BMCs,

- the achievement of results for BMCs,

- the design and implementation of the PBL program,

- the extent to which the PBL compares with international experience, and

- ways in which the program can be improved to support CDB’s strategic objectives.

Evaluation Approach and Methodology

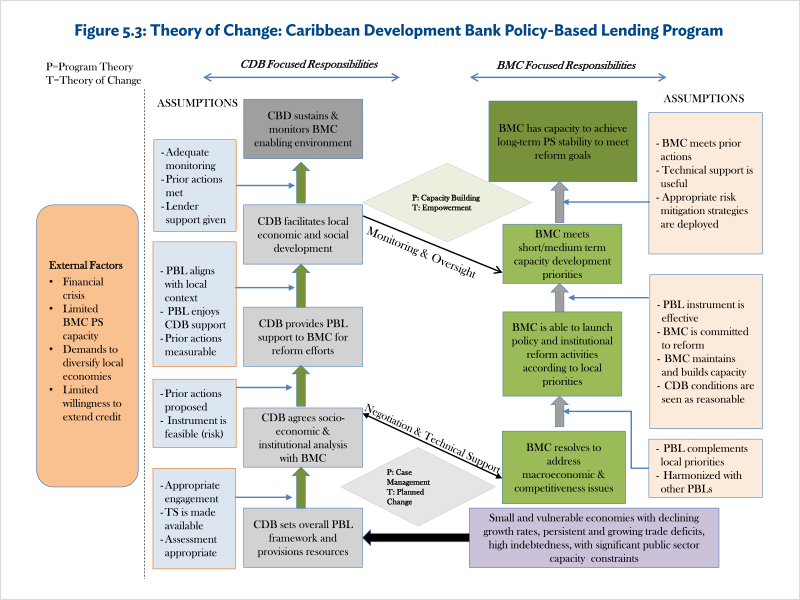

This was a theory-based evaluation, with a reconstructed theory of change for the PBL program (Figure 5.3), validated with stakeholders. It tested numerous assumptions that underlay the program.

BMC = borrowing member country, CDB = Caribbean Development Bank, PBL = policy-based lending, PS=public sector, TS=technical support

Figure 5.3 suggests that the logic of CDB’s PBL program has two parts: (i) the conditions set by CDB, and (ii) the conditions actually implemented by BMCs. CDB created the PBL initiative to enable BMC governance reforms that would not otherwise occur. Specifically, PBL was intended to assist “small and vulnerable economies with declining growth rates, persistent and growing trade deficits, high indebtedness, with significant public-sector capacity constraints.13Caribbean Development Bank. 2013. Policy Paper: Framework for Policy-Based Operations - Revised Paper. BD_72/05 Add. 5”To support such economies, CDB prepared funding contracts with conditions negotiated with borrowers to address policy-based reforms. CDB assessed whether BMCs were carrying out the conditions of these contracts through regular monitoring and oversight as shown by the cross arrows between the two causal pathways in the figure. For their part, BMCs accepted the conditions contained in those contracts with the long-term objective of ensuring macroeconomic stability and public capacity to meet their development goals.

In program theory literature, the change theory that best explains whether CDB can create such conditions is called “planned behaviour.” This theoretical framework suggests that if CDB creates appropriate application, review, and implementation processes for its PBL program, and there is a clearly stated need and rationale for the PBL intervention, then borrowers will utilize the program to buttress their own reform efforts and prevent breakdowns or crises in their local governance systems. For their part, BMCs will not successfully effect the reforms unless conditions are built that maximize their room or flexibility for programs of reform based on their own identification of needs. Such flexibility provides the local confidence and commitment needed to respect PBL agreements.

Extensive evidence was gathered to test the assumptions in the theory of change (Table 5.5). This included in-depth case studies of PBL operations in Barbados, Jamaica, Grenada, and St. Vincent and the Grenadines; a meta-analysis of PBL experience at other MDBs; extensive interviews with BMC and CDB officials; and analysis of secondary (mostly macroeconomic) data.

Table 5.5: Assumptions Tests by Evaluation Criterion

|

Assumptions Tests |

|

|

1: Relevance of the PBL program |

|

|

If the first set of assumptions holds, examine the next questions. |

|

|

2: Appropriateness of the conditions |

|

|

If the first and second sets of assumptions hold, examine the next questions. |

|

|

3: Observable effects |

|

PBL = policy-based lending, PBL = policy-based operation.

Findings and Conclusions

Need, relevance, and rationale. It is beyond dispute that MDB lending has been important to BMCs, enabling them to address fiscal pressure and debt management, as well as to encourage economic and social sector reforms. However, different parties emphasized different aspects of the instrument. Borrowers tended to be driven by short-term fiscal pressures, particularly in the aftermath of the 2007–2009 financial crisis. PBL support played a role in helping some of them through that period, and at times they agreed to reform programs that they did not entirely buy into. For their part, lenders (including CDB), while recognizing fiscal exigencies, understood the PBL to be primarily an instrument that provided incentives to implement reforms. At times they required large numbers of “prior actions” from BMCs as conditions of PBL support.

To some extent this difference in perspective had to do with sequencing: in one view relieving fiscal pressure first to allow the space to eventually undertake reforms; and, in the other, adopting reforms that will eventually help open fiscal space. While these views could co-exist in the broad space of acknowledged need for PBL lending, their differences did have implications for the expectations and approach to PBL negotiations by the respective parties.

A number of MDBs and other partner organizations—including the World Bank, IMF and IDB— brought significant funding to policy-based lending in the region. Respondents had clearly reflected on the appropriate role and value added of CDB among these larger players. They alluded to CDB’s more detailed understanding of BMC contexts, its closer working relationships with governments, and the potential for brokering harmonized reform packages that included non-economic governance elements.

Planning and design. The quality of the process by which borrowers and lenders came to an agreement on the design of an intended reform program was an important predictor of eventual success. The evaluation observed that in the first generation of PBL operations there was a perceived imbalance in negotiating leverage between CDB and borrowers (favouring CDB). As a result, the ownership of the prior actions by the BMCs and their commitment to expected reform outcomes were sometimes less than complete. This was compounded in cases where CDB’s consultation did not involve a sufficient range of stakeholders, particularly those who would either have a role in implementing reforms or would be affected by them. Not hearing these views at the outset came at the cost of lack of buy-in or even resistance to intended reforms during implementation. More recent PBL design processes had performed better in this regard.

Apart from the process of arriving at a design, the actual nature and number of prior actions and expected reform outcomes were important determinants of effectiveness. Again, it was observed that there was an evolution from earlier to more recent PBOs. Pre-2013 PBOs tended to require larger numbers of prior actions across multiple sectors, and these often lacked a clear causal linkage to the higher-level expected reform outcomes. BMCs felt that prior actions did not always reflect national reform priorities, and that the cost of delivering on them sometimes exceeded the value of the PBL on offer. More recently, there have been examples of PBOs with streamlined prior actions in fewer areas. These actions have been better calibrated to the scale of assistance being offered, and more likely to be achieved. There has also been some evidence of successive PBOs building on earlier efforts, with prior actions requiring incremental progress from earlier to later loans.

Assessing at the outset whether borrowers had the capacity to implement intended reforms was a necessary element of good PBL planning. Providing TA responsively during implementation to address bottlenecks was also important. To date, this has not been an area of strength for CDB.

Harmonization of CDB PBOs with those of other MDBs became stronger over the evaluation period. However, an unanticipated consequence of this harmonization has been that closely synchronising CDB’s prior actions with those of other lenders has somewhat limited CDB’s flexibility to tailor its own offerings. Such tailoring could grow out of CDB’s particular understanding of BMC context, or its interest in promoting reforms focused on non-economic areas.

Implementation. The timeliness of fund disbursement under the PBL mechanism was efficient. That said, there were some instances of tranche payment in the absence of all prior actions being met (which is likely to have been related to earlier findings regarding numerous conditions and national capacity constraints). CDB’s monitoring of PBOs was inconsistent. Project supervision and completion reports were sometimes missing, and monitoring was more oriented toward verifying completion of prior actions than to assessing progress towards reform outcomes. Evidence was not always available to corroborate project completion report statements.

The quality of PBL results frameworks was not optimal. The link between prior actions (outputs), and economic, sectoral, and institutional reforms (outcomes) was not always clear. Proposed indicators and targets were not necessarily good measures of the outcomes with which they were (or should have been) associated. BMCs lacked the capacity to report on the range of expected results. Statements of risk tended to be generic across PBOs, missing the need for mitigation strategies specific to each PBO’s expected outcomes and national contexts.

The revised framework document of October 2013 placed renewed emphasis on the longer-term reform orientation of policy-based lending, and the value of programmatic PBL. At the same time, there are varying stages of readiness for reform implementation across the region, and a menu of PBL instruments, including multitranche PBOs, may be needed to respond to different situations.

Results achievement. Completion of PBO prior actions for three of the four case study countries (Barbados, Jamaica, and Grenada) was verified. This totaled 113 prior actions across five PBOs. In the fourth case study country (Saint Vincent and the Grenadines), completion of 19 out of 23 originally planned prior actions was verified; the other four were waived with Board approval to allow a second-tranche disbursement.14In view of the challenging economic circumstances at the time, and the otherwise positive reform trajectory, the CDB Board authorized disbursement of the second tranche of the 2009 PBL, notwithstanding delays in completion of four prior actions. A separate 2010 PBL operation for St. Vincent and the Grenadines used an unusual formulation involving six prior actions and seven post-disbursement conditions or indicators. Completion of the prior actions was verified at the time of the evaluation, along with four of the post-disbursement conditions.Among the short-term outcomes of the PBL operations were:

- debt management improved;

- fiscal space created that allowed BMCs to bolster social program reforms or reduce economic stress on individuals and families;

- conditions for investment improved to bolster key industries (such as tourism, by reducing wait times at border crossings, which could be attributed in part to PBL); and

- critical management systems such as audit, budgeting and planning improved, contributing to increased public sector management efficiency.

Because of the number of causal factors in play, including support from other PBL lenders and global economic events, it was difficult to attribute medium-term outcomes directly to CDB lending. Nonetheless, BMC officials across all case studies indicated that a coordinated, targeted, and ongoing program of reform supported by lenders such as CDB had ensured momentum, leading to improved economic and social program performance. For example, Jamaican respondents indicated that its 2008 PBL was, “a critically important intervention in Jamaica, and with the support of other MDBs helped to identify first generation structural reforms on which the recent fiscal gains have been premised.”

Generally, however, it was not feasible for the evaluation to gather a sufficient amount of directly attributable evidence to support statements of causal linkage between CDB’s PBL support and higher-level medium-term outcomes. This is a common difficulty in PBL assessment across MDBs, although as mentioned above an improvement in CDB’s specifications, measurement, monitoring, and reporting on results would help.

Summary Comments and Recommendations

Over the 10 years since the introduction of PBL at CDB, there had been an evolution in practice that reflects CDB’s learning and experience in managing the instrument, and its observation of how other MDBs also manage PBL. The loans addressed an evident need among BMCs.

The findings and conclusions of this evaluation, based on evidence generated from the document review, documented case studies, and a wide range of interviews, suggested that several key factors increased the likelihood of PBL operations achieving their desired results. These were:

- clear objectives and results logic, with indicators and targets that can be measured and verified;

- a selective focus on a manageable number of expected reform outcomes;

- agreement on a limited number of prior actions that are clearly linked to those outcomes;

- good understanding of external risks, and elaboration of mitigation strategies;

- an engagement process with BMCs that engenders ownership and commitment on the part of borrowers;

- a menu of PBL options that offers the right instrument calibrated to borrowers’ reform readiness;

- an understanding of national capacity constraints and, where needed, provision of affordable TA to address them;

- designation of an identified champion in the national public service with responsibility and authority for achieving reform results; and

- consistent monitoring to identify when conditions are met, and the degree of progress towards reform outcomes.

Although the evaluation found that CDB’s PBL was increasingly taking account of these factors, it offered the following recommendations to encourage further progress.

(i)CDB should review its practice of management for development results (MfDR) in the PBL program. It should ensure that its design process respects good MfDR practice, with clearly stated expected outcomes and indicators that are specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and time-bound (SMART). The robustness of the results framework should be the primary criterion for quality at entry. Where necessary, staff responsible for PBL design and monitoring should have access to training in MfDR techniques, as well as occasional expert advice from a results specialist.

(ii)CDB should develop more tailored risk mitigation strategies. To date, such strategies have tended to be generic across PBOs. Instead, they should be more closely matched to the specific circumstances of the national context and reform program.

(iii)CDB’s policy-based lending should focus on a limited number of key outcomes, with prior actions that are causally linked to them. The selection of outcomes should take account of: (a) the limited size of CDB’s PBL loans, (b) BMC priorities and CDB’s own country strategy, and (c) an agreed longer-term reform program in mind. This focus should ideally be maintained over time, with prior actions in successive PBOs building incrementally on one another.

(iv)National ownership and leadership are indispensable to the success of development reform programs. CDB should facilitate these to the greatest extent possible through collegial engagement with BMCs in PBL design and implementation. This will require consultation with a sufficient breadth of national stakeholders, at both leadership and implementation levels, to gain commitment and follow through on reform objectives and prior actions. A good practice to be encouraged is the designation of a “champion” from the BMC’s public sector for implementation of targeted reforms.

(v)Small economies experience serious capacity constraints in attempting to implement reform programs. These need to be anticipated and responded to as part of an effective PBL program. Relative to other MDBs, CDB has an intimate understanding of the contexts and constraints of its BMCs. Yet it has carried out only limited needs analysis or uptake of CDB TA in connection with its PBL loans. CDB should investigate the reasons for this, ensure that potential TA requirements are well analyzed at the design stage, and that flexibility is shown when they are offered during implementation.

(vi)Different countries find themselves at different stages of readiness for PBL-supported reform programs. Although the 2013 revised framework for PBL lending emphasized placing loans within a longer-term reform context (through a programmatic series approach), some BMC stakeholders contend that multitranche PBL may continue to be well suited to BMCs requiring more structured and predictable prior actions. CDB should ensure that the right PBL instrument is matched to each reform context.

(vii)Monitoring and completion reports are important parts of the effective implementation and accountability of the PBL program. CDB should ensure that these tasks are consistently carried out, and that they have a results focus, for all PBL. This should go beyond verifying that prior conditions have been met, and should assess the extent to which these actions are contributing to reform outcomes. CDB should also consider extending monitoring efforts beyond the timeframe of PBL disbursements. The outcomes of interest are, after all, medium- and longer-term reforms, and CDB will wish to track these as part of its overall country strategy process.

Management Response

Management expressed general agreement with the findings, conclusions, and recommendations of the OIE evaluation, with one area of exception. It felt that evaluators had underappreciated the extent of staff engagement with borrowers in arriving at agreed prior actions and reforms, and thus also understated the degree of national ownership of PBL-facilitated reform programs. It acknowledged, however, that consultation processes could have been better documented, that results frameworks should have more clearly established the logic of the links between prior actions and reforms, and that monitoring could be improved.

Management accepted all recommendations and provided a time-bound action plan for their implementation. The Oversight and Assurance Committee, a subcommittee of the Board of Directors, annually monitors completion of these actions.

- 13Caribbean Development Bank. 2013. Policy Paper: Framework for Policy-Based Operations - Revised Paper. BD_72/05 Add. 5

- 14In view of the challenging economic circumstances at the time, and the otherwise positive reform trajectory, the CDB Board authorized disbursement of the second tranche of the 2009 PBL, notwithstanding delays in completion of four prior actions. A separate 2010 PBL operation for St. Vincent and the Grenadines used an unusual formulation involving six prior actions and seven post-disbursement conditions or indicators. Completion of the prior actions was verified at the time of the evaluation, along with four of the post-disbursement conditions.

Emerging Issues

In the period since OIE last examined policy-based lending, use of the instrument has if anything become more prominent in CDB’s overall lending program, and PBL has been the subject of considerable Board discussion. In response to the impacts of several category 5 hurricanes, CDB has deployed exogenous shock response PBOs, which were contemplated in the 2013 policy framework but had not previously been used. This has prompted thinking on how policy-based lending could better incentivize policy and institutional actions that would build ex ante resilience to natural hazards. CDB’s recently approved Disaster Management Policy and operational guidelines in fact suggest that a specific “resilience PBL” instrument be prepared. Deferred draw-down approaches have also been discussed.

The global pandemic is having an enormous impact on the Caribbean’s tourism-dependent economies and their fiscal and debt balances. CDB has responded with both a debt moratorium on outstanding OCR loans (to selected countries), and new PBL aimed at preserving macroeconomic stability. Elevated lending has in turn revived discussion of the allowable upper limit for total policy-based lending. Given the circumstances, the Board has granted an increase to 38% of outstanding balances, but only until 2023. At the same time, it has asked Management to further review of experience with the instrument and its guiding framework.

Annex

Summary of Reform Milestones

The chapter provides an informative overview of the findings of five assessments, including two Office of Independent Evaluation (OIE) evaluations, of Caribbean Development Bank (CDB) policy-based operations (PBOs). Among many other findings, it conveys clearly how the institution’s practice of policy-based lending (PBL), as well as the associated framework and guidance, has evolved over the roughly 15 years since it was officially initiated. Like other multilateral development banks (MDBs), CDB has moved over time toward the body of good practice identified in an ever-growing PBL literature. As expected, the favorable evolution of CDB’s PBL practice notwithstanding, there is room for further improvement.