Introduction

The objective of the chapter is to pool the results of recent evaluations of program-based operations (PBOs) during the period 2005–2019. Over the period 2005–2019, Independent Development Evaluation at the African Development Bank Group (AfDB) carried out two major independent evaluations of the PBO instrument: (i) in 2011, an Evaluation of Policy-Based Operations in the African Development Bank, which covered the period 1999–2009;1Operations Evaluation Department. 2011. Evaluation of Policy-Based Operations in the African Development Bank, 1999-2009. Abidjan: AfDB. and (ii) in 2018, an Independent Evaluation of African Development Bank Program-Based Operations, which covered the period 2012–2017.2Independent Development Evaluation. 2018. Evaluation of Program-Based Operations in the African Development Bank, 2012-2017. Abidjan: AfDB. The chapter draws on these two evaluation reports, supplemented by recent data on certain aspects.

Section 2 describes the historical development and use of policy-based lending, 2005–2019.

Section 3 covers PBO performance over the period 2005–2019. Section 4 concludes the chapter.

Historical Development and Use of Policy-Based Lending by the African Development Bank, 2005–2019

Definition

PBOs are fast-disbursing financing instruments, which the AfDB provides to countries in the form of loans or grants. They address the actual, planned or unexpected development financing requirements of AfDB’s regional member countries (RMCs).3African Development Bank. 2012. Policy on Program-Based Operations. Abidjan.

PBOs are intended to support nationally owned policy and institutional reforms in RMCs, and to make available predictable medium-term finance to support priority spending to meet medium- and long-term development goals. They provide funds to the country’s Treasury, to be executed using the national financial management system. PBOs are fungible and are provided together with associated policy dialogue and economic as well as sector work, all in support of nationally driven policy and institutional reforms.

Following in the footsteps of the World Bank (which first created structural adjustment loans to provide balance of payment finance to countries in return for policy and institutional reforms), the PBO instrument, formerly known as policy-based lending (PBL), was introduced in 1988 through the Bank Group Policy on Structural and Adjustment Lending.4African Development Bank. 1988. Policy on Structural and Adjustment Lending. Abidjan.The same year, AfDB also introduced Policy-Based Lending Operations: Supplementary Guidelines and Procedures5African Development Bank. 1988. Policy-Based Lending Operations: Supplementary Guidelines and Procedures. Abidjan.to provide guidance on the use of the instrument. Until then, lending had focused exclusively on investment projects. In 2004, AfDB adopted Guidelines on Development Budget Support Lending6African Development Bank. 2004.Guidelines on Development Budget Support Lending.Abidjan.and Guidelines for Policy-Based Lending on Governance,7African Development Bank. 2004.Guidelines for Policy-Based Lending on Governance.Abidjan. complemented by a Legal Note on Sector Budget Support Operations8African Development Bank. 2005. Legal Note on Sector Budget Support Operations. Abidjan.in 2005.

The Governance, Economic and Financial Management Department was established in 2006 to lead AfDB’s work on PBOs. In 2008, AfDB’s Governance Strategic Directions and Action Plan, 2008–2012 (GAP I),9African Development Bank. 2008. Governance Strategic Directions and Action Plan: GAP 2008–2012. Abidjan.was adopted to guide AfDB’s governance work in its RMCs. Using a combination of PBOs, institutional support projects (ISPs), technical assistance, economic and sector work (ESW), policy dialogue, and advisory services, AfDB has emphasized economic and financial governance in its RMCs. In 2010, after an independent evaluation, a commitment was made as part of the African Development Fund (AfDF)10The standard abbreviation for the African Development Fund is ADF. However, to avoid possible confusion with the Asian Development Fund, which uses the same abbreviation, in this book the abbreviation AfDF has been used to signify the African Development Fund. replenishment negotiations that a comprehensive new policy would be prepared to consolidate existing good practices and streamline requirements for policy-based operations. Consequently, in 2011, the Program-Based Operations Policy, 2012–2017 (henceforth “the 2012 policy”) was adopted. The subsequent guidelines, which were finalized in March 2014, complemented the 2012 policy by providing additional practical guidance on the design and implementation of PBOs in AfDB, while re-establishing good practice in aid effectiveness in relation to predictability, country ownership, donor coordination, policy dialogue, and reporting.

- 3African Development Bank. 2012. Policy on Program-Based Operations. Abidjan.

- 4African Development Bank. 1988. Policy on Structural and Adjustment Lending. Abidjan.

- 5African Development Bank. 1988. Policy-Based Lending Operations: Supplementary Guidelines and Procedures. Abidjan.

- 6African Development Bank. 2004.Guidelines on Development Budget Support Lending.Abidjan.

- 7African Development Bank. 2004.Guidelines for Policy-Based Lending on Governance.Abidjan.

- 8African Development Bank. 2005. Legal Note on Sector Budget Support Operations. Abidjan.

- 9African Development Bank. 2008. Governance Strategic Directions and Action Plan: GAP 2008–2012. Abidjan.

- 10The standard abbreviation for the African Development Fund is ADF. However, to avoid possible confusion with the Asian Development Fund, which uses the same abbreviation, in this book the abbreviation AfDF has been used to signify the African Development Fund.

Different Types of Program-Based Operations

There are four types of PBOs: general budget support (GBS), sector budget support (SBS), crisis response budget support (CRBS), and import support. The fourth category is markedly different from the others, which provide funds directly to the national treasury. Import support goes to the central bank. Fiduciary and audit standards are also different for import support.

- General budget support (GBS). A loan or grant that provides non-earmarked financial transfers to the national budget in support of policy and institutional reforms that are established in the country’s national development plan or national poverty reduction strategy and are included in the country’s budget priorities. This financing is accompanied by policy dialogue to support on-going government-led policy reforms in multiple sectors as well as other complementary instruments, where appropriate.

- Sector budget support (SBS). A loan or grant that involves policy and institutional reforms in a particular sector of AfDB’s operational priorities, supported by unallocated financial transfers to the national budget. This financing is accompanied by policy dialogue in support of a particular sector and other complementary instruments, where appropriate.

- Crisis response budget support (CRBS). A fast-disbursing loan or grant to mitigate the adverse impact of a crisis or shocks. CRBS is available to the full range of RMCs: middle-income countries (MICs), low-income countries (LICs), and Transition states11Transition States are countries where the main development challenge is fragility(for which a risk assessment must be carried out). The crisis may be political, economic, or humanitarian. CRBS appraisal reports need to justify the decision to use the instrument based on the nature of the crisis. There is limited scope for policy dialogue at times of crisis, but the instrument can be used to open the door for future policy dialogue. AfDB streamlines its processes to fast-track the preparation and disbursement of PBOs as part of CRBS operations.

- Import support.A loan or grant that involves the transfer of financial resources to the central bank or is used to boost reserves in the case of a balance of payment deficit. Import support is not the strategic focus of AfDB. The instrument is to be used only in exceptional cases as part of a coordinated donor action (e.g., with the International Monetary Fund) to mitigate short-term macroeconomic instability in any RMC.

The 2012 policy makes clear that budget support can be provided either as a stand-alone operation or as programmatic support. The policy highlights the usefulness of a programmatic approach for supporting medium-term policy reforms, while maintaining stand-alone operations as an option.

- Stand-alone operations. A single disbursement against the fulfillment of prior actions during the year of approval. Policy dialogue is limited to a 1-year period.

- Programmatic operations. A series of single-year operations in a multi-year framework. This involves a series of single-tranche operations that are sequentially presented to the AfDB Board of Directors, within a medium-term framework specified at the outset. Indicative triggers are included in an overall multiple-year appraisal report and are adapted to changing circumstances at each phase of the program. At the end of each phase, a streamlined appraisal document is prepared, indicating the prior actions taken in advance of the next loan or grant as well as the triggers for subsequent operations in the series.

- Programmatic tranching. Single loan operations with a series of tranches set within a multi-year framework, all approved upfront in one appraisal report. Under this model, the conditions precedent for the disbursement of each tranche are identified and approved by the Board at the time of approval. This requires a high degree of certainty on reform actions and timing but has the advantage of reducing transaction costs for both AfDB and the RMC.

At the AfDB, PBO resources are not subject to earmarking and are not related to the cost of the reforms supported, but rather to country financing requirements and AfDB’s available lending envelope. From 2009 to 2019, PBOs constituted 17%–21% of overall annual approvals.

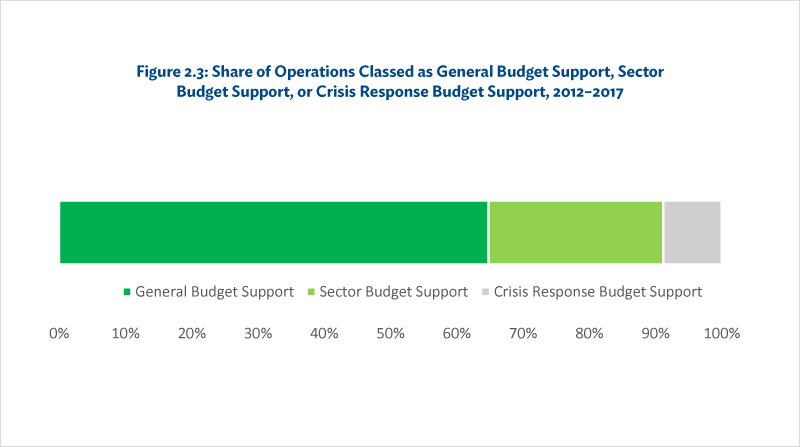

Within that timeframe, GBS represented 65% of AfDB operations. Following the adoption of the 2012 policy, the share of SBS increased to 26.4%. The CRBS instrument was introduced in 2012 by the policy and represented 8.7% of all PBOs approved during 2012–2017.

Despite AfDB’s stated preference for programmatic operations, single-standing operations (SSOs), still account for a third of approved projects. Programmatic models are the preferred option for AfDB (as in other multilateral development banks), because: (i) reforms are medium-term in nature, and (ii) they allow development partners more leverage to support reforms. Since 2012, 42% of PBOs have been designed as programmatic operations or programmatic tranching (24%).

The coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic has disrupted African countries’ economies and the livelihoods of millions of people. In response, AfDB has introduced initiatives to support the governments of its RMCs as they take measures to mitigate the human and economic impact of the pandemic. As part of its response, AfDB has used CRBS to respond quickly to crises. This is not the first time AfDB has faced such a major emergency, in 2014 it responded to the Ebola crisis affecting Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone using the PBO instrument to strengthen the countries’ health systems so that they could tackle the outbreak. The use of CRBS is guided by AfDB’s 2014 operational guidelines on the programming, design and management of PBOs and by simplification measures introduced by the $10 billion COVID-19 Rapid Response Facility (CRF)12COVID-19 Response Facility. https://www.afdb.org/en/news-and-events/press-releases/african-development-bank-group-unveils-10-billion-response-facility-curb-covid-19-35174 AfDB launched in April 2020.

In addition to the CRF, a number of measures have been launched as part of the COVID-19 outbreak and its economic consequences, including a $3 billion Fight COVID-1913The Fight Covid-19 Social Bond. https://www.afdb.org/en/news-and-events/press-releases/african-development-bank-launches-record-breaking-3-billion-fight-covid-19-social-bond-34982social bond, and $2 million in emergency assistance to support measures led by the World Health Organization14The emergency assistance for the World Health Organization (WHO) to reinforce its capacity to help African countries contain the COVID-19 pandemic and mitigate its impacts. https://www.afdb.org/en/news-and-events/press-releases/african-development-bank-approves-2-million-emergency-assistance-who-led-measures-curb-covid-19-africa-35054to curb the spread of the disease. Since the approval of the CRF, 28 CRBS operations have been prepared and approved for the benefit of 40 RMCs. Specifically, 26 AfDF countries received support with a total of $1,244 million and 14 African Development Bank countries for a total of $2,364 million.15AfDB. First Quarterly Progress Report Implementation of the COVID-19 Response Facility (2021). The unit of account (UA) is the currency for AfDB projects.

The focus of CRBS operations has been on supporting emergency responses to the health, social, and economic crises brought about by COVID-19. AfDB’s policy dialogue with governments has centered on the formulation and content of COVID-19 response plans, in particular on ensuring that these plans cover not only the health dimensions of the crisis, but also respond to the social and economic fallout. AfDB has accorded high priority to safeguarding the transparency and accountability of COVID-19 expenditures and programs, and has taken the lead in addressing this as part of its policy dialogue with RMCs. In the medium term, the focus of the dialogue will shift to increasing AfDB’s engagement on the reforms required for recovery and on building economic resilience, which can be pursued once the crisis is over.

- 11Transition States are countries where the main development challenge is fragility

- 12COVID-19 Response Facility. https://www.afdb.org/en/news-and-events/press-releases/african-development-bank-group-unveils-10-billion-response-facility-curb-covid-19-35174

- 13The Fight Covid-19 Social Bond. https://www.afdb.org/en/news-and-events/press-releases/african-development-bank-launches-record-breaking-3-billion-fight-covid-19-social-bond-34982

- 14The emergency assistance for the World Health Organization (WHO) to reinforce its capacity to help African countries contain the COVID-19 pandemic and mitigate its impacts. https://www.afdb.org/en/news-and-events/press-releases/african-development-bank-approves-2-million-emergency-assistance-who-led-measures-curb-covid-19-africa-35054

- 15AfDB. First Quarterly Progress Report Implementation of the COVID-19 Response Facility (2021). The unit of account (UA) is the currency for AfDB projects.

Use of Program-Based Operations

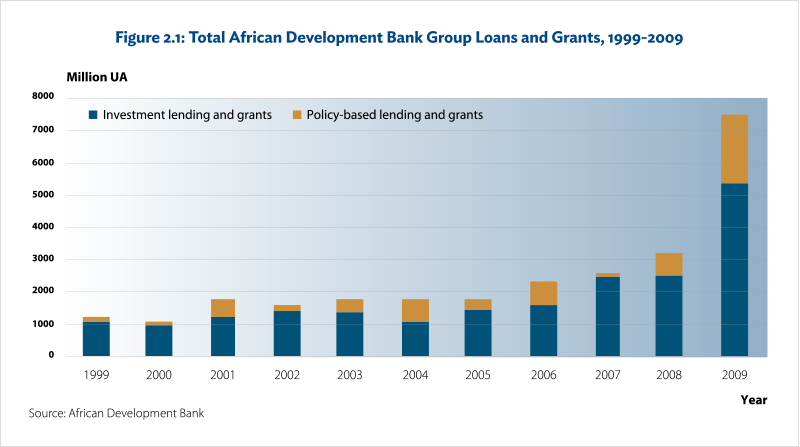

There has been a substantial increase in AfDB’s use of PBOs in terms of the number and amount of approvals since 2005. Between 2005 and 2008, AfDB’s total operations grew steadily before a spectacular increase in 2009, in response to the global financial crisis.16Operations Evaluation Department. 2011. Evaluation of Policy-Based Operations in the African Development Bank, 1999-2009. Abidjan: AfDB.Total PBO approvals over the 2005–2009 period amounted to UA6.1 billion, comprising UA3.6 billion in AfDB loans (21 operations), UA1.8 billion in AfDF loans (68 operations), and UA0.7 billion in AfDF grants (31 operations). A third of AfDB PBOs over the period were approved in 2009, accounting for 49%, by value, of the total AfDB PBOs approved during 2005–2009. One operation (Botswana Economic Diversification Support Loan) dominated the approvals, with a value of just over UA1 billion. The top five users of PBOs, by value, during the 2001–2009 period, were all MIC countries (Morocco, Botswana, Tunisia, Mauritius, and Egypt). Within active AfDF countries, more than half (20 out of 36) had PBOs, which accounted for over 20% of their total operations. In eight countries, PBOs represented 10%–20% of their operations, but in eight others less than 5% of their total AfDF financing was provided as PBOs. The largest AfDF users of PBOs, in terms of total finance provided, were Ethiopia, Tanzania, Ghana, and Mozambique, all of which received more than UA200 million over the 1999-2009 evaluation period. The AfDF countries with the largest number of separate operations were Tanzania, Burkina Faso, and Cape Verde (each with six); and Ethiopia, Mali, Zambia, Benin and Lesotho (each with five).

AfDB has approved 91 PBOs during the 2012–2017 period)17Independent Development Evaluation. 2018. Evaluation of Program-Based Operations in the African Development Bank, 2012-2017. Abidjan: AfDB.with an approval value of UA7.2 billion.18Operations Evaluation Department. 2011. Evaluation of Policy-Based Operations in the African Development Bank, 1999-2009. Abidjan: AfDB.Of the 91 approved operations during 2012–2017, 68% were part of a series of operations. This represents an increase on the period covered in the previous evaluation (1999–2009) in terms of both average annual approval volumes19AfDB, Operations Evaluation Department (2011).and the average number of operations approved per year.20Ibid.The PBO share of AfDB financing increased to 78% compared to 59% in the earlier period. For 2012–2017, disbursement stood at 95% of approvals at the time of writing. The remaining undisbursed funds were related to 2017 approvals.

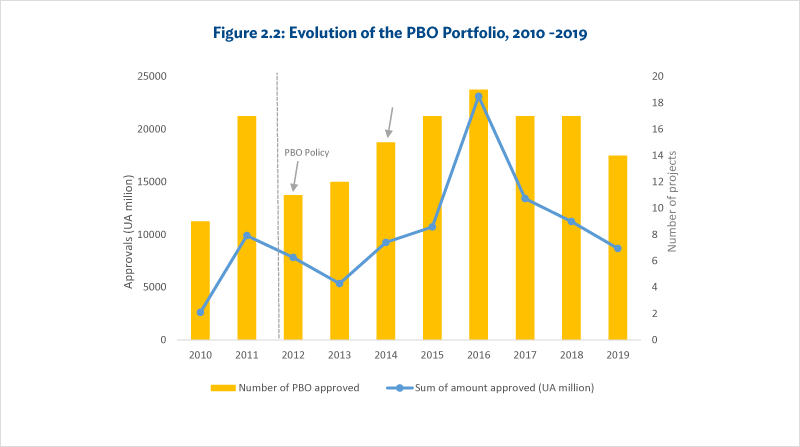

Since the approval of the 2012 policy, there was a steady increase in the number of operations approved until 2016 (Figure 2.2),21The 2011 evaluation included data only up to 2009, so data for 2010 and 2011 are also included to ensure there is no gap in longer-term approval data. when approval volumes spiked.22Three specific large approvals contributed to this spike: Algeria, Egypt, Nigeria As a result, in 2017 the Board and Senior Management agreed to introduce a ceiling of 15% for of AfDB operations for PBOs, which led to some PBOs planned for approval in 2017 being delayed or reconsidered and a decrease in approvals in 2017. The AfDF countries had a 25% PBO ceiling in place for the full evaluation period. The ceiling applies to the AfDF 3-year cycle, meaning that annual approvals fluctuate. In terms of other key portfolio trends as they relate to the direction pushed by the 2012 policy, there has been an increase in the proportion of PBOs which support sector governance, as opposed to only core public finance management (PFM) issues. Programmatic or multi-year operations now make up the majority of operations approved since 2012 (66%), with the remainder being SSOs.

Over three-quarters (by amount) of PBOs approved since 2012 have been for operations in MICs, although this translates to about one third in terms of the number of operations. The average size of PBOs is larger in MICs than in either LICs or transition states and larger in 2012–2017 than in 2010–2011. Over the same period, the average size of PBOs in LICs and transition states showed a slight decrease. The volume of PBOs provided as grants has also decreased and they accounted for just 6.1% in 2012–2017. In total, AfDB provided PBOs to 34 countries in Africa between 2012 and 2017. Of these, Morocco made the most use of AfDB’s PBO instrument, with 10 operations during that period.

Each country category was associated with a specific type of PBO. CRBS was predominant in transition states (75% of the total number), while GBS was most often used in LICs (68% of the total number). About half of SBS was directed at MICs (46% of the total number).

More recently, AfDB approved 33 PBOs in 24 countries between 2018 and 2020, amounting to more than UA1.9 billion. Reflecting previous trends, the largest amounts of PBOs were directed at MICs, including Morocco, Egypt, and Angola.

PBO = program-based operations, UA = unit of account (the currency for AfDB projects).

Note: The evaluation period is 2012–2017. The previous periods (2010–2011 and 2018–2019) were added for context and to complete the story of the evolution of the portfolio since the 2011 evaluation, which covered 1999–2009 approvals.

- 16Operations Evaluation Department. 2011. Evaluation of Policy-Based Operations in the African Development Bank, 1999-2009. Abidjan: AfDB.

- 17Independent Development Evaluation. 2018. Evaluation of Program-Based Operations in the African Development Bank, 2012-2017. Abidjan: AfDB.

- 18Operations Evaluation Department. 2011. Evaluation of Policy-Based Operations in the African Development Bank, 1999-2009. Abidjan: AfDB.

- 19AfDB, Operations Evaluation Department (2011).

- 20Ibid.

- 21The 2011 evaluation included data only up to 2009, so data for 2010 and 2011 are also included to ensure there is no gap in longer-term approval data.

- 22Three specific large approvals contributed to this spike: Algeria, Egypt, Nigeria

Policy Reform

Over the period 1999–2009, out of a total of 102 PBOs, only seven supported reforms in the energy, agriculture, social and financial sectors. Most PBOs were focused on PFM and on improving the business climate.

In line with the spirit of the 2012 policy, AfDB is making greater use of PBOs to support governance reforms in the health, energy, transport, and agriculture sectors in addition to its core work in economic and financial governance. Although about 65% of PBOs during the period were officially listed as GBS (Figure 2.3), the proportion of SBS increased over previous years. In addition, a closer look at the content of the PBOs reveals that 59% (whether listed as GBS, SBS or CRBS) included a focus on sector governance rather than concentrating on core economic governance areas such as PFM. This compares with 31% for the 2 years preceding the policy. At the same time, 75% of PBOs in the 2012–2017 periodalso included PFM components.

Notably, all PBOs can be mapped to at least one of AfDB’s “High 5s,”23Building on its existing 2013–2022 strategy, AfDB outlined five development priorities: Light up and Power Africa; Feed Africa; Industrialize Africa; Integrate Africa; and Improve the Quality of Life for the People of Africa. as identified in the Ten-Year Strategy and the Governance Strategy and Action Plan II (2014–2018), or supported governance issues which cut across them. The three High 5s that received the most support during the period were: (i) Industrialize Africa (mainly through private sector environment reforms); (ii) Quality of Life (including education and social protection); and, (iii) Light up and Power Africa (the fastest growing area with almost all PBOs approved in the last 3 years). AfDB’s New Deal on Energy in Africa highlights the importance of addressing deficiencies in country policy and regulatory frameworks. PBOs with a focus on helping governments to provide an environment conducive to doing business is relevant to AfDB’s existing governance and private sector development strategies as well as to the “Industrialize Africa” High 5.

During the Ebola outbreak of 2014, which was responsible for the deaths of 11,325 people in West Africa, the three countries most affected by the crisis (Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone) were characterized by weak links between government and society, inadequate governance, continued insecurity, and weak institutional capacity. Strengthening their recovery and response capacity was seen as vital to ensure early detection and avoid the outbreak expanding beyond the affected countries. The last case of Ebola was recorded in Guinea in June 2016. AfDB used the SBS instrument and was able to learn from its experience in managing a crisis, which subsequently enabled it to respond quickly and efficiently to the COVID-19 pandemic. Several lessons were drawn from the evaluation of the two projects, which made up part of AfDB’s response to the Ebola crisis:24AfDB. 2015. Technical Assistance to Support Countries (Guinea, Sierra Leone and Liberia). Abidjan; and AfDB. 2014. Strengthening West African Health Systems. Abidjan.

- Active community consultation, engagement, social mobilization and proper analysis of the social environment contribute to good project design.

- Including government officials as members of the project implementation units for large and complex projects is important.

- Operational flexibility in the design and implementation of the project can be helpful in meeting project objectives.

- Country ownership and empowerment of local organizations through community engagement and social mobilization are key for the success of any project that operates in the community.

- The lack of a unified regulatory framework is likely to hamper the deployment of volunteer health workers and other support mechanisms.

- Embedding capacity building as part of an emergency or crisis response that faces severe restrictions on movement and personal contacts does not work.

- The lack of a monitoring and evaluation officer for a project of this magnitude adversely affects smooth and efficient project delivery.

- 23Building on its existing 2013–2022 strategy, AfDB outlined five development priorities: Light up and Power Africa; Feed Africa; Industrialize Africa; Integrate Africa; and Improve the Quality of Life for the People of Africa.

- 24AfDB. 2015. Technical Assistance to Support Countries (Guinea, Sierra Leone and Liberia). Abidjan; and

AfDB. 2014. Strengthening West African Health Systems. Abidjan.

Debt Relief

The 2012-2017 evaluation did not find out whether PBOs took place in conjunction with debt reduction or relief support programs by other donors. Instead, it assessed the relevance of PBOs within AfDB’s portfolio and the extent to which they adhered to its own policy and guidelines as well as international good practices. Macroeconomic stability is one of the conditions for PBO eligibility, as AfDB needs to considers debt sustainability. The aim is to ensure that loan conditions do not compromise the debt sustainability of recipient countries.

Cooperation with Multilateral Development Banks and the International Monetary Fund

AfDB has made substantial progress in its use of PBOs. In 1999, it was heavily dependent on the World Bank and to a lesser extent the IMF for the analysis and design of its PBOs. The only instruments available to AfDB were structural and sectoral adjustment operations, which often encountered implementation difficulties and delays resulting from weak country ownership and unsuccessful attempts to leverage policy change using complex conditionalities.

The evaluation of PBOs in 2018 highlighted how AfDB had coordinated with other development partners, most notably in the identification and appraisal periods. AfDB staff give high importance to coordination and invest in upfront work with other development partners. However, the evaluation also found that AfDB had found it difficult to sustain these initial high levels of coordination throughout the implementation phase. AfDB’s approach was in line with the G20 Principles for Effective Coordination between the IMF and MDBs on Policy-Based Lending in 2017, which proposed that all MDBs align behind the IMF with regard to countries facing macroeconomic vulnerability.

Harmonization with other development partners was one of the 2012 policy’s five PBO eligibility criteria and is also considered core to international good practice. Nevertheless, the guidelines make it clear that “the criterion of harmonization does not prevent AfDB from providing PBOs when no other development partner is doing so. Indeed, in such cases, teams are expected to consider the potential of the PBO to leverage other support and influence. With regards to coordination with the IMF in particular, expectations have recently changed.”

At the identification and appraisal stages, AfDB’s efforts to coordinate with other development partners were rated satisfactory in 82% of cases. Such coordination was clearest in the 23% of PBOs which made use of joint performance assessment frameworks (PAFs). Where PAFs did not exist, and even in cases where AfDB was the only partner to provide assistance in the form of budget support, sound justifications and evidence of coordination were found. For example, in Chad, AfDB worked closely with the European Union and the World Bank, including through joint missions during the first Public Finance Reform Support Programme, although the practice was not fully sustained under the second. In Ghana, the joint budget support framework had broken down by the time the Public Financial Management and Private Sector Competitiveness Support Programme (PFMPSC) was appraised; however, AfDB’s decision to provide a PBO and to work closely with IMF and the World Bank was well justified.

In the context of in-depth PBO assessments, a consistent theme on coordination emerged. Coordination was strong during the identification and appraisal stage where the concerned government took up its leadership role, but was not always maintained throughout implementation. Around two-thirds of survey respondents had a positive view of AfDB’s coordination with other development partners, although views were slightly more positive among AfDB staff than among RMC officials. Egypt provides an example of good practice in terms of coordination between the AfDB and the World Bank, since the coordination that began at identification and appraisal continued into implementation.25With the exception that, for the third phase, the two institutions are now running on different schedules, since AfDB faced some delays, which reduced the extent to which it has been possible to conduct missions jointly. Although the IMF program was not in place by the time AfDB approved the first a series of PBOs, it followed soon after and there was regular liaison between the three institutions during the planning stages. In the Seychelles, appraisal for the first in a series of PBOs for both the AfDB and the World Bank was closely linked to the IMF’s assessment, and the government took the lead in bringing the development partners together to support related reform programs, but this coordination was not sustained in later years.

There have been cases where AfDB has proceeded with a PBO in the absence of an on-track IMF program before the G20 principles were adopted. These included three countries that did not have an IMF program: two are MICs (Angola and Nigeria) and one is a transition state (Comoros, although the PBO was not CRBS).26This figure does not include Egypt since the IMF program was agreed shortly after PBO approval. In addition to the in-depth PBO assessments, the desk review highlighted that in Algeria, Comoros, and Mauritania, IMF programs were not on track but an IMF letter of comfort and/or notes on the country’s relationship with IMF through Article IV consultation were included in the appraisal package.

- 25With the exception that, for the third phase, the two institutions are now running on different schedules, since AfDB faced some delays, which reduced the extent to which it has been possible to conduct missions jointly.

- 26This figure does not include Egypt since the IMF program was agreed shortly after PBO approval.

Evaluation of the Performance of Program-Based Operations, 2005–2019

Evaluation of African Development Bank Policy-Based Operations, 1999–2009

The first independent evaluation of PBOs was undertaken in 2011 and assessed AfDB’s use of PBOs over the period 1999–2009 (footnote 71). The evaluation examined how effectively AfDB had used PBOs to support national development objectives, with a focus on AfDB’s policies and procedures for PBOs. It was based on: (i) a review of the literature and comparative experience with PBOs in other development agencies, (ii) a review of AfDB’s institutional and policy framework, (iii) six country case studies, and (iv) four case studies of other significant operations.

The evaluation concluded that AfDB had made substantial progress in its use of PBOs. In 1999, AfDB was heavily dependent on the IMF and the World Bank for the analysis and design of its engagement in structural and sectoral adjustment operations. As of 2011, AfDB operated as a significant partner in joint donor budget support arrangements, and the record of its engagement, as shown by the country case studies, was largely one of success. AfDB had developed a cadre of staff with strong experience in the design and management of budget support. The establishment of country offices had significantly improved AfDB’s ability to engage in national policy and budget processes and had strengthened its monitoring and supervision of PBOs (even though decentralization progressed far more slowly than planned).

AfDB had strengthened its organizational capacity and structure for the design, appraisal, management, and monitoring of PBOs, although some aspects still required further development. It had proved highly responsive to the international economic and financial instability that affected RMCs during 2008 and 2009. AfDB was able to design and implement operations to meet the urgent financial requirements of its clients and these operations provided a platform from which longer-term structural reforms could be addressed. It also made important contributions to the development of budget support arrangements under the Fragile States Facility; in Liberia, for instance, AfDB played a leading role in moving other development partners toward budget support.

The evaluation found that, while AfDB had succeeded in engaging effectively in joint budget support arrangements and in mobilizing rapid responses for fragile and crisis-affected countries, there were some shortcomings in its policies and practices. Its numerous policies and guidelines were not being consolidated or updated. Project procedures were not being fully documented, and were designed for investment operations rather than specifically tailored to PBOs. There was a lack of clarity about how results should be defined and measured for PBOs, information systems were weak, and audit and fiduciary risk issues needed to be addressed.

Independent Evaluation of African Development Bank Program-Based Operations, 2012–2017

The evaluation was based on seventeen background reports, as well as on a series of focus groups and reference group discussions (footnote 72). The evaluation scope covered the 9127Sixty of these relate to programmatic operations, where two or three separate operations together are considered a series, but each phase in the series is approved as an individual operation. The number of single PBOs plus PBO series is 51.PBOs approved between 2012 and 2017, with a collective approval value of UA7.2 billion.

The evaluation was designed to: (i) identify factors which had enabled or hindered good performance, (ii) draw lessons for AfDB, and (iii) identify specific recommendations to help AfDB to optimize the effective use of the PBO instrument in future. Specifically, the objectives of the evaluation were to provide credible evidence on: (i) how AfDB was programming, designing and managing its PBOs in accordance with the 2012 policy and other elements of good practice;28There are various sources of advice on “good practice.” The most relevant for AfDB is OECD-DAC. 2006. Harmonising Donor Practices for Effective Aid Delivery. Volume II. Paris: OECD, which laid out a set of principles for the provision of budget support consistent with the 2005 Paris Declaration.(ii) the performance of PBOs in specific areas; (iii) the factors that had enabled or hindered achievement of PBO objectives; and (iv) lessons that could inform AfDB’s future use of PBOs to ensure consistent good practice and to support achievement of the High 5s.

The evaluation addressed three overarching questions.

These three questions were broken down into eight sub-questions, addressed through over 40 criteria.

- 27Sixty of these relate to programmatic operations, where two or three separate operations together are considered a series, but each phase in the series is approved as an individual operation. The number of single PBOs plus PBO series is 51.

- 28There are various sources of advice on “good practice.” The most relevant for AfDB is OECD-DAC. 2006. Harmonising Donor Practices for Effective Aid Delivery. Volume II. Paris: OECD, which laid out a set of principles for the provision of budget support consistent with the 2005 Paris Declaration.

Methodology

A generic theory of change for AfDB PBOs was constructed based on AfDB documents, consultations with internal stakeholders, and the methodology endorsed by the Development Assistance Committee of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD-DAC) for evaluating budget support operations. The theory of change helped to refine the evaluation questions. Individual theories of change were also developed for each of the 10 in-depth country studies based on the generic version.

The evaluation had seven components and each used different sources of data and analytical techniques. In addition, the evaluation was based on a thorough inception phase which included two staff focus groups and interviews with 42 internal stakeholders, including eight executive directors and 12 members of senior management.

For the 10 in-depth studies, a cluster approach was used. This allowed strong evidence to be collected within specific areas but limited the extent to which the findings could be generalized across the full portfolio. The two focus areas of energy and the private sector enabling environment (PSE) were identified early in the design stage following analysis of: (i) the recent use of PBO funds, (ii) the availability of evidence, and (iii) the pertinence of these areas to future directions for AfDB, particularly in support of the High 5s. In addition to evaluating these two focus areas, the evaluation also examined the PFM components of the PBOs (present in nine of the 10 countries). It is important to note that, for the two general budget support (GBS) cases that included a broad range of targeted sectors in addition to energy, PSE, and PFM, those other sectors were not the focus of in-depth analysis, although the delivery of all reforms was assessed.

Within these two focus areas of energy and the private sector enabling environment, cases were selected according to the following considerations.

- Evaluability The sample included countries with PBOs that were at a reasonably mature stage of implementation (least 12 months since approval) so some influence could be expected on intermediate outcomes (known as “induced outputs,” see Table 2). All 2017 approvals were therefore excluded.

- Contemporary relevance The sample covered countries with relatively recent PBOs, whose design and implementation should reflect the 2012 policy, and where the process of implementation could still be recalled by those interviewed. This meant most of the cases came from the 2014–2016 period.

- Diversity in types of PBOs In selecting the cases, the goal was to include examples of SBS, GBS, single-standing operations, programmatic operations, and programmatic tranching.

- Diversity in country contexts The sample covered: (i) MICs, LICs, and transition countries; (ii) countries in at least four of the five sub-regions in which AfDB operates; and (iii) anglophone, francophone, and lusophone countries.

- Diversity in size of PBOs The sample included some of the largest and most important PBOs, intermediate PBOs, and small PBOs.

Ten countries and 16 operations were covered by the in-depth studies (Table 2.1). Collectively, they accounted for UA2,155,040 in approvals and 36% of PBO approvals by amount in 2012–2016. The assessments covered energy, PSE, and PFM29PFM is a cross cutting area and most PBOs (Energy and PSE) have a PFM component.. However, the sample was not designed to be generalizable across the full portfolio. In particular, PBOs with a focus on social sectors—which have also been an important part of the portfolio and are managed by a different department—were not covered.

Table 2.1: Program-Based Operations Covered by the In-Depth Assessments

|

Country |

PBO Operations |

Approval Date |

PBO Type |

Disbursement |

Net Loan Amount (UA million) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Energy Cluster |

|||||

|

Angola MIC Lusophone Southern Africa |

Power Sector Reform Support Programme |

2014 |

SBS |

100% |

705 |

|

Comoros Transition Francophone East Africa |

Energy Sector Support Programme |

2014 |

SBS |

100% |

4 |

|

Energy Sector Reform and Financial Governance support Programme |

2012 |

GBS |

100% |

2 |

|

|

Burkina Faso LIC Francophone West Africa |

Energy Sector Budget Support Programme |

2015 |

SBS |

100% |

20 |

|

Nigeria MIC Anglophone West Africa |

Economic Governance, Diversification and Competitiveness Support Programme |

2016 |

GBS |

100% |

445.6 |

|

Tanzania LIC Anglophone East Africa |

Power Sector Reform and Governance Support program |

2016 |

SBS |

100% |

37.4 |

|

Power Sector Reform and Governance Support Program |

2015 |

SBS |

100% |

35.5 |

|

|

Private Sector Environment Cluster |

|||||

|

Egypt MIC Arabic and Anglophone North Africa |

Economic Governance and Energy Support Program Phase II |

2016 |

GBS |

100% |

371.3 |

|

Economic Governance and Energy Support Program Phase I |

2015 |

GBS |

100% |

371.3 |

|

|

Mali Transition Francophone West Africa |

Programme d'appui aux réformes de la gouvernance économique Phase II |

2016 |

GBS |

0% |

23.2 |

|

Programme d'appui aux réformes de la gouvernance économique Phase I |

2015 |

GBS |

100% |

15 |

|

|

Morocco MIC Francophone North Africa |

Morocco Economic Competitiveness Support Programme |

2015 |

GBS |

100% |

83.5 |

|

Ghana LIC Anglophone and Francophone West Africa |

Public Financial Management and Private Sector Competitiveness Support Programme Phase II |

2016 |

GBS |

100% |

35 |

|

Public Financial Management and Private Sector Competitiveness Support Programme Phase I |

2015 |

GBS |

100% |

40 |

|

|

Seychelles HIC Anglophone East Africa |

Inclusive Private Sector Development and Competitiveness Programme Phase II |

2015 |

GBS |

100% |

7.4 |

|

Inclusive Private Sector Development and Competitiveness Programme Phase I |

2013 |

GBS |

100% |

14.9 |

|

GBS = general budget support, HIC = high-income country, LIC = low-income country, MIC = middle-income country, PBO = program-based operations, SBS = sector budget support.

Source: AfDB

he evaluation was subject to a number of limitations. Each of these was taken into account in how the evaluation was designed and reported.

First, at the design stage, the evaluation team explicitly limited the extent to which the overarching question (ii), on results, would be addressed.30AfDB. IDEV Approach Paper, IDEV Information Note to the Board, Final Inception Report(2017).This limitation related both to how far up the results chain the evaluation could go in assessing AfDB’s contribution to results. Additionally, the decision to focus primary data collection on performance within the two sectors and PFM covered by the two clusters of in-depth assessments allowed to give strong internal validity. Other data were used to establish whether the observed patterns had validity beyond those sectors.

Second, secondary data were not always available. For example, in some cases project completion reports, validations, and implementation progress and results reports (IPRs) were not available. In addition, AfDB does not systematically record its policy dialogue with countries. These constraints were mitigated by using other data sources where possible.

Third, given resource constraints, the balance between depth and breadth was based on stakeholder information needs. The 10 in-depth cases were chosen to maximize learning in the specific areas of energy and PSE, nine of the 10 cases also included PFM. The survey sought to bring in broader staff and RMC views, as did focus groups for staff. The project portfolio documentation review used a representative stratified sample. It did not include an assessment of the quality of analytical work.

Fourth, recent cases (from early 2018) were included to ensure that the evidence was contemporary, which also helped with the availability of informed staff and stakeholders. However, since many reforms are medium-term in nature, this meant that fewer results were available.

Fifth, to understand how PBOs had contributed to results, the in-depth assessments followed a uniform methodology designed to reflect the specificity of the PBO instrument and to maximize the learning potential for AfDB. Four different assessments were conducted (Table 2) to arrive at the overall assessment. The overall assessment was satisfactory, and the weakest area was AfDB’s contribution to the direction or the pace of achieving landmark policy changes. In order to mitigate risks when it came to evaluating the results of PBOs, the evaluation compared the results with those of other internal and external evaluations of AfDB operations to validate them.

Table 2.2: Assessing the Effectiveness of Program-Based Operations and Their Contribution to Landmark Policy Changes

| Country’s Achievement of RMF Indicators | AfDB Contribution to Landmark Policy Changes a |

| Induced output bexecution ratio | Achievement of landmark changes c |

| Overall assessment of effectiveness by country, including induced outputs and final outcomes | Evidence of PBO influence on landmark changes |

AfDB = African Development Bank, PBO = program-based operations, RMF = results measurement framework.

Defined in Box 1.

The term induced outputs is aligned with international methodological standards on evaluating PBOs developed by OECD. However, induced results may also be considered to be an intermediate outcome. The theory of change in Annex 2 of the evaluation report outlines the kind of results anticipated at this level.

Landmark policy changes constitute (i) changes introduced as a result of decisions made at senior levels of government, and (ii) substantive changes, with a clear link to a desired final outcome. Thus, the mere adoption of a plan of action for reform would not be a landmark policy change, but the implementation of legislative or regulatory reforms as a result of that plan would constitute a landmark policy change.

Key Findings

The evaluation found that PBOs remained a relevant and useful instrument for AfDB and its clients, although they were challenging to design and manage effectively. The evaluation found the relevance of the PBOs in AfDB’s portfolio to be broadly satisfactory, based on their programming and design and their broad adherence to AfDB’s own policy and guidelines and to international good practice. With regard to the achievement of reform objectives, the overall picture was also satisfactory. However, it was much harder to find evidence of AfDB’s influence on reform direction and speed. Regarding sustainability, even in the presence of strong ownership, concerns about the institutional and financial dimensions of sustainability meant that the overall outlook for sustainability in the sectors examined was unsatisfactory.

Despite having deployed UA7.2 billion as PBOs 2012–2017, AfDB had failed to invest in its own institutional infrastructure to obtain maximum value for money from the instrument. As was well reflected in the 2012 policy, PBOs were expected to form part of a “package of support” in order to ensure that they influenced and supported reform agendas, while also providing important funding. This package included analytical work to inform technical input, policy dialogue and capacity support. In practice, while there was some variation across countries, overall AfDB had underperformed when it came to policy dialogue, despite its strong position as a trusted partner. This was partly due to its institutional arrangements; a lack of clarity about who was responsible for policy dialogue; the structure of how the dialogue should be conducted, reported, and coordinated; and a lack of investment in human resources to conduct it. In addition, AfDB had underperformed in providing timely and adequate capacity support and specialized technical advice, partly due to the limited menu of instruments available to do so. These shortcomings had implications for how well AfDB was able to influence or add value to country reform paths.

Programming issues. A range of programming issues were examined and, while the overall picture was assessed to be broadly satisfactory, the evaluation identified areas that could be strengthened. First, for the large majority of the PBOs reviewed (94%, excluding CRBS), their use was envisaged in either the relevant country strategy paper (CSP) or the midterm review (MTR), in line with the policy. However, in the majority of cases, the assessment against the eligibility criteria was made for the first time during the PBO preparation phase. In terms of the type of PBO, the justification for the type chosen could have been be stronger, especially when the PBO did not use the recommended programmatic approach. Second, in approximately two-thirds of the operations reviewed, the analytical underpinnings used were clearly listed and relatively complete. However, exactly how this work informed or underpinned the design of the operation was not clear. Third, while risk assessment was assessed as satisfactory in two-thirds of the operations reviewed, reputational risk was rarely explicitly considered. The risk mitigation measures, such as future capacity support to address current risks, were generally not convincing within the timeframe of a PBO.

Alignment with country and AfDB priorities. This was assessed positively on the basis of the document review and in terms of stakeholder perceptions. All the PBOs could be mapped to at least one of the High 5s or supported crucial governance issues which cut across them. AfDB had also succeeded in expanding use of the instrument to support sector reforms in addition to economic and financial governance. Nearly 80% of survey respondents had positive views on the alignment of PBOs with country policy frameworks.

Coordination. There were many good examples of how AfDB had coordinated with other development partners, notably during the identification and appraisal periods. AfDB staff had taken coordination seriously and had invested in upfront work with other development partners. However, the in-depth assessment illustrated how difficult AfDB had found it to sustain these initial high levels of coordination throughout the implementation phase. Moreover, following the adoption of the G20 Principles for Effective Coordination between the IMF and MDBs on Policy-Based Lending in 2017, in countries facing macroeconomic vulnerability MDBs needed to align behind the IMF.

Designing PBOs for results. The overall picture was satisfactory, although some shortcomings were identified. Although two-thirds of the PBO appraisal reports examined stated there was an important role to be played by complementary inputs, only a handful explained how this was to be achieved. All PBO results frameworks defined baselines, targets and means of verification, and integrated prior actions and triggers. However, over a third were less than satisfactory because of: (i) weaknesses in presenting a convincing results chain; (ii) high proportions of process- and action-based indicators; and (iii) a lack of realism, particularly for single-year operations. The use of conditions was suitably selective; in programmatic operations these linked from one phase to the next in order to plot a medium-term path, and they were linked to broader dialogue frameworks. However, weaknesses were noted when the number of prior actions was high, opportunities for identifying triggers were missed, or the level of ambition for prior actions was not appropriate.

Gender and environment. The evaluation found that AfDB had missed valuable opportunities provided by the PBOs to address gender equality and environmental reform issues at the policy level. Just over a third of the PBO project appraisal reports (PARs) that were assessed included gender-related indicators and 7% included environmental or climate-sensitive indicators. The opportunity to push gender equality and environmental concerns varied according to the type of PBO. However, particularly in the energy sector, PBOs can provide valuable opportunities to shift national policies in support of AfDB’s ambitions of inclusive and green growth.

Efficiency. Broadly speaking, PBOs were broadly disbursed and implemented in a timely way, although some receiving countries said that disbursement was unpredictable. In line with expectations for the PBO instrument, the evaluation found that AfDB had disbursed the funds fully and, compared with investment projects, quickly. In addition, implementation progress was very rarely identified as a cause for concern. Nine of the 10 in-depth assessments were efficient in terms of transaction costs and the time taken to disburse the funds. However, perceptions of timeliness and transaction costs varied among both staff and RMC officials.

Technical assistance. Perceptions of the efficiency and transaction costs of technical assistance or institutional support provided to support PBOs was negative. Such support, when it was provided, was slow and tended to arrive toward the end rather than beginning of a PBO series. This was partly because capacity support tended to be designed in parallel with PBOs rather than in advance, and partly because of the limited set of instruments AfDB had available to provide small items of technical assistance, all of which operated like full projects rather than as rapidly deployable expertise.

Policy dialogue. AfDB did not use policy dialogue sufficiently or make best use of its “African Voice” to ensure PBO results. This finding is not dissimilar to that of the 2011 evaluation which described AfDB as “punching below its weight” when it came to policy dialogue. Only three of the 10 in-depth assessments had satisfactory frameworks for policy dialogue in the targeted sectors. The deficiencies that emerged in relation to policy dialogue can be broadly categorized as: (i) lack of clarity over who is leading and responsible for policy dialogue, especially after approval;

(ii) limited capacity to engage in in-depth technical dialogue in some areas; (iii) lack of structured planning or reporting for policy dialogue efforts, including through AfDB’s normal supervision channels; and (iv) lack of a medium-term strategy to capitalize on doors that may be opened by a PBO after formal completion. In the survey, fewer than a third of respondents were clearly positive when asked about the extent to which AfDB mobilizes appropriate resources for policy dialogue. In the 10 countries investigated, only five had a satisfactory framework for policy dialogue.

Policy guidance. The existence of the 2012 policy helped AfDB to improve its approach to PBOs and to make it more consistent; however, there were areas where implementation was wanting. The policy provided clarity on the authorizing environment and on a range of important issues, including the type of instrument, when it should be employed, on what basis and with what objectives. The policy was broadly aligned with good practices. Although it clearly set out activities or changes that needed to take place in order to facilitate implementation, not all aspects of implementation have gone as planned. For example, there have been delays in producing the supporting guidelines, a glaring lack of training, and unfinished business in ensuring an enhanced role for country offices. The guidelines, which are described as a living document, have not been updated and there has been no additional guidance on new reform areas, such as energy. The guidelines have not been following the adoption of the G20 principles. The survey and focus groups both also revealed staff demand for more guidance in areas such as policy dialogue, working in post-conflict contexts, and results measurement.

Institutional arrangements. Some of AfDB’s practices were out of line with both its own policy and the practices at the World Bank and the European Union. First, PBO design and management remained somewhat centralized and led by either the Governance and Public Financial Management Coordination Office (ECGF) or by sector departments. The extent to which country offices had taken up ownership varied significantly. Second, in practice, there was no centralized unit that provided specialized support to PBO teams. ECGF staff had been task-managing most of AfDB’s GBS. This lack of a central support unit, and the limited guidance and training provided to staff, was in stark contrast to the support available at the World Bank and the European Union.

Effectiveness. Overall, the assessment of PBO effectiveness, which focused on energy, PSE, and PFM, was broadly satisfactory. The evaluation highlighted areas where AfDB could focus attention in order to strengthen results and specifically how it could contribute to the direction and pace of reforms. Data from project completion reports and country strategy and program evaluations by the Independent Development Evaluation indicated that the satisfactory assessment was likely to reflect the effectiveness of the broader portfolio.

- All of the 10 cases achieved or partially achieved all, or the majority, of the reform actions listed in the results framework. In only one case were 25% of outputs considered to have been not achieved. In all other cases, at least 75% of the reforms were assessed to have been either fully achieved, partially achieved, or achieved with significant delay. With regard to the achievement ratios by sector covered, no clear pattern emerged. No sector performed notably better than any other. At an aggregate level, in seven of the 10 countries covered by the in-depth studies the overall effectiveness in terms of the achievement of the objectives stated in the results measurement framework (RMF) was considered satisfactory.

- Across the 2131Separate assessments were made for each of the relevant sectors: PFM, energy, and PSE. The total number of assessments was 21. Where the PBO was part of a series, the assessment was for all parts of the series completed or well underway.individually assessed components, two-thirds were assessed satisfactory in terms of the achievement of “landmark policy changes.” Within a PBO RMF, some actions can be much more important than others, although an RMF can include a large number of “tick-box” type items alongside more fundamental issues that have the potential to drive change and contribute to transformative outcomes. Such indicators were identified as “landmark policy changes.” Where these were not achieved, it is worth noting that the sample included a transition state (Comoros); two cases where the principal focus of the PBO was in another area (Tanzania and Seychelles); and one where the second part of the planned series never took place (Nigeria).

- AfDB’s influence on the achievement of landmark policy changes was not always evident. In one third of the components, AfDB’s influence on either the direction or pace of reforms was evident and was usually achieved through analytical work, technical inputs, and policy dialogue. AfDB staff respondents to the survey supported the view that AfDB’s influence was limited, and strongest at the appraisal stage.

Sustainability. The sustainability of PBOs in energy, PSE and PFM was assessed to have been unsatisfactory, particularly in relation to the institutional and financial dimensions of sustainability. Only four of the 10 in-depth assessments had good prospects for sustainability. Almost all of the 10 had laid strong foundations for sustainability in terms of government ownership and leadership, which should be at the core of the decision to proceed with a PBO. However, the weak institutional and financial sustainability undermined the positive assessments in terms of ownership. While this trend was clear for energy, PSE and PFM, it cannot be generalized across the whole PBO portfolio.

Contextual, design, and management factors. The evaluation evidence from AfDB and from other institutions providing budget support in Africa indicates that the most frequently identified factors relating to country context were: (i) ownership, country capacity, having a “champion” for reforms; (ii) the country’s socioeconomic status; and (iii) country systems. The most frequent factors relating to the budget support mechanism were: (i) quality of design, programming, development partner coordination; and (ii) quality of monitoring and choice of indicators. The single most frequently cited enabling factor was the quality of design. In terms of hindering performance, the most frequently highlighted were: insufficient policy dialogue, high efficiency and transaction costs, poor choice of indicators, weak monitoring, and poor predictability.

The most significant factors associated with achievement of landmark policy changes,32Budgetary or institutional changes of substance and influence targeted by PBOs within the set of intermediate outcomes (induced outputs) identified in the theory of change.stronger even than the country’s socioeconomic status, were: programming, design, and efficiency factors; technical assistance; the operation being part of a series; and the existence of a country office.

- 31Separate assessments were made for each of the relevant sectors: PFM, energy, and PSE. The total number of assessments was 21. Where the PBO was part of a series, the assessment was for all parts of the series completed or well underway.

- 32Budgetary or institutional changes of substance and influence targeted by PBOs within the set of intermediate outcomes (induced outputs) identified in the theory of change.

Recommendations

Updating the guidance framework. Changes in the international context, calls for more internal guidance, and shortcomings in design and implementation indicate that the 2014 guidelines on implementing the 2012 policy need to be updated. The analysis indicates that a strong relationship between the government and the development partners and the presence of an ongoing IMF program are fundamental to the achievement of reforms.

Recommendation 1: Update or complement the PBO guidelines

- Reflect AfDB’s response to the 2017 G20 principles on coordination with the IMF.

- Provide detailed guidance to staff on the most challenging areas of the results frameworks, including: conducting effective policy dialogue, post-conflict concerns, and promoting reforms in support of gender equality and environment and climate change.

Enforcing compliance. Although the assessment of programming and design was satisfactory (most of the PBOs in the sample were assessed to have been satisfactory against selected criteria), AfDB aims for every PBO to be satisfactory, especially in relation to 100% compliance with the provisions of AfDB’s own policy and guidelines.

Recommendation 2: Fully enforce the provisions of the 2012 policy

- Use of non-programmatic operations or operations that are not already programmed in the country strategy paper (CSP) or CSP midterm review (MTR) should be done only on an exceptional basis as per the 2012 policy. Such operations should have a convincing rationale and should be based on sound analysis, including an evaluation of the alternative options.

- Conduct fiduciary risk assessments when the decision is first made to use a PBO. The assessment should be updated at appraisal, and the proposed risk mitigation measures should be adequate to address the identified risks within the timeframe of the planned PBO.

Focusing PBO ambitions. Some PBOs were spread over a broad range of reform areas. Moreover, analysis was not always undertaken to identify where AfDB could add most value, including through the expertise it could provide, or which reform actions would pave the way to “landmark policy changes.”

Recommendation 3: Design all future PBOs with a focus on a limited number of medium-term reform areas from within broader government reform plans

- Assess which reforms have the potential to pave the way to landmark policy changes.

- Evaluate AfDB’s complementarity with other development partners and with its wider portfolio.

- Judge the ability of AfDB to add value in these areas, especially in terms of analytical work, expertise, and policy dialogue.

A tight focus should be combined with a strengthening of the medium-term dimension in the design, i.e., programmatic PBOs should follow a clearly defined multi-year reform path, as well as paying attention to how AfDB might accompany reform processes over the medium term over one or more PBOs.

Prioritizing policy dialogue. Policy dialogue is a central part of how PBOs achieve results and how AfDB adds value to reform processes. Yet there was a lack of clarity and insufficient prioritization of policy dialogue in AfDB PBOs.

Recommendation 4: Reflect the vital role of policy dialogue in PBOs in practice

- Make unequivocally clear at the design stage what policy dialogue will entail, what mechanisms will be used, what the priorities will be, how policy dialogue will be underscored by relevant technical expertise, and who will be responsible for conducting and reporting it. This can be done by including a standard annex on policy dialogue priorities and responsibilities in the PBO’s project appraisal report. This would provide a starting point that could be adapted over time to respond to new policy needs as they arise.

- Align practices with plans in the 2012 policy and the development and business delivery model (DBDM) by more clearly allocating responsibility for PBO design and management to country offices and regions. Ensure country offices and regions have sufficient resources and the necessary reporting structures to take up this responsibility, and provide strong technical support from headquarters teams. (Alternatively, if AfDB prefers to operate a centralized model, the policy and DBDM documents should be adjusted to reflect this approach to remove any confusion).

- Ensure that budget lines for PBO appraisal and supervision take account of the need to involve the appropriate range of expertise in the case of PBOs that cover a range of areas.

Using technical assistance more efficiently. The other complementary input supporting PBOs was technical advice and capacity support. AfDB has tied its hands by relying on a limited menu of instruments on which it can call to provide this support, and some of these do not provide support in a timely or efficient manner.

Recommendation 5: Provide PBOs with appropriate and timely expertise and capacity support

- Examine how to refine and expand AfDB’s menu of options when it comes to providing expertise and technical assistance. This should include: (i) reviewing how to make the MIC Trust Fund and other trust funds more flexible so as to improve their relevance; (ii) investigating other instruments, including short-terms options, such as framework contracts with specialist companies that can provide quick and high-quality technical expertise that is not available internally; and (iii) providing longer-term solutions such as a fast-track technical assistance scheme.

- Require clear justification if relevant capacity support or expertise is not already in place or at least planned by the time approval for any PBO is sought.

Investing in supporting institutional infrastructure for PBOs. AfDB has not appropriately invested in its most important tool for making PBOs an effective and value-for-money instrument: its people. It has no central support team charged with supporting the instrument at a technical level or for cross-learning purposes. It has established only minor differences between quality at entry and processes for PBOs as compared with those for investment projects.

Recommendation 6: Invest in the supporting infrastructure for PBOs

- Invest in continuous training for staff involved in PBO design and implementation. Such training could take the form of an accreditation scheme and draw on the rich experience that has been gained internally, while also drawing on lessons from elsewhere.

- Invest in upfront analytical work to support PBO design and the focus of policy dialogue and capacity support, which will require forward planning and resources to allow teams to conduct or commission it.eview the extent to which AfDB’s quality assurance processes are appropriate for PBOs, in particular the readiness review. Strengthen supervision and reporting of supervision.

Overview of Management Response to the Independent Evaluation of Program-Based Evaluation, 2012–2017

Management welcomes the Independent Evaluation of AfDB PBOs 2012-2017 and agrees with the findings and recommendations of the evaluation, which it considers to be useful in further improving the Bank’s important work in providing PBOs. The Bank and its clients consider PBOs to be effective instruments to support macro-fiscal stability and advance wide-ranging policy reforms in RMCs. The evaluation comes at a time when there is a great deal of interest in and debate around the use of the PBO instrument. Overall, management

The use of the PBO instrument by AfDB increased significantly over the period 2005–2019, leading to calls for caution. In response to these concerns and in order not to compromise its financial stability, AfDB introduced unbreachable limits of 25% of allocations from the AfDF window and 15% of the allocations from the AfDB window, in terms of volume.

The instrument has demonstrated its relevance, particularly during crisis situations and in support of structural reforms in the PFM, energy, transport, and health sectors.

Although the performance of the instrument was rated generally satisfactory by two independent evaluations, these evaluations also found that AfDB was still not able realize the instrument’s full potential. PBOs need to be used as a package of support, combining budget support, policy dialogue, and technical assistance.

Nevertheless, AfDB’s management response to the findings and recommendations of the 2018

Annex: AfDB Management Response to the Independent Evaluation of Program-Based Evaluation, 2012–2017

Management welcomes the Independent Evaluation of AfDB PBOs 2012-2017. The Bank and its clients consider PBOs to be effective instruments to support macro-fiscal stability and advance wide-ranging policy reforms in RMCs. The evaluation comes at a time when there is a great deal of interest in and debate around the use of the PBO instrument. It examines how the Bank has been using the instrument since 2012, when the Board approved the PBO Policy, and focuses on the performance of PBOs in three sectors (energy, PSE and PFM) while drawing lessons and providing recommendations to optimize the effective use of the PBO instrument in the future. Overall, management agrees with the findings and recommendations of the evaluation, which it considers to be useful in further improving the Bank’s important work in providing PBOs.

Management of PBOs

The evaluation finds a broadly positive picture of the Bank’s time efficiency in disbursing and implementing PBOs. However, this efficiency was jeopardised when technical assistance (TA) was required to support the implementation of reforms, but the Bank was unable to provide it in a timely manner. Management agrees that the Bank’s lack of flexibility to respond quickly in providing TA or other expertise affects the Bank’s ability to always engage effectively, and it will look into how to enhance/expedite responsive TA provision.

The evaluation examines the Bank’s engagement in policy dialogue and concludes that the Bank is not fully using its comparative advantage to ensure PBO results through policy dialogue. Issues affecting the quality of policy dialogue included lack of clarity on responsibility for policy dialogue, what policy dialogue entails, and how it is planned and reported. Management takes note of these findings and fully agrees with the recommendations put forward to strengthen the central role of policy dialogue in PBOs.

Supervision and reporting compliance are other issues raised by the evaluation. While supervision and monitoring are taking place, the evaluation noted as an issue the lack of systematic documentation on these key activities. Management shares the concern that lack of documentation undermines internal knowledge sharing and reporting and will monitor compliance with the Bank’s standard reporting requirements.

The evaluation also examines the institutional framework for the management of PBOs, contrasting the level of support, guidance and training provided to Bank staff managing PBOs with that provided to colleagues in two peer organisations. It points out that the responsibility for PBOs has remained relatively centralised although the PBO Policy and DBDM envisage a stronger role for country offices. It highlights the important role of country offices in ensuring smooth dialogue, while noting that the extent to which country offices have actually taken up ownership of the dialogue varies significantly. The evaluation emphasises the need for a strong technical team to provide guidance, support and qualitative input during PBO preparation. Bearing in mind the need for urgency in effective High 5s implementation, management sees that the Bank needs to invest more resources to support technical staff development; hence it plans to develop an accreditation scheme/training programme to begin addressing the shortfalls in staff capacity.

Performance of PBOs

The evaluation concludes that PBO effectiveness in PFM, PSE and energy is broadly satisfactory, especially in terms of achieving “landmark reforms”. However, it also highlights the difficulty of determining the Bank’s influence, noting that the degree of influence varies by sector and area of focus and providing positive examples from the energy sector. Management takes note of these findings, which support its view that PBOs are relevant instruments to effectively support critical reforms, including for the High 5 areas. Management also agrees with the lesson on the importance of carefully identifying the appropriate areas of focus of the operation and ensuring active engagement with countries and partners.

The evaluation examines the sustainability of the reforms PBOs supported in energy, PSE and PFM, and found that it was assured in just 40% of the cases. Management takes particular note of this finding. Sustainability is critical, and achieving it is a perennial challenge faced not only by the Bank, but also by its peer MDBs that provide PBOs. It requires, first and foremost, strong and long-term country commitment to reform implementation. To address this issue, Management agrees with the evaluation recommendation—that increased use of the programmatic approach is beneficial not only to achieving reforms, but also to sustaining them. Management is also of the view that sustainability is an issue that should feature regularly in development partners’ in-country consultations. It considers the lessons provided in this regard to be pertinent and useful.

Conclusion

This is a timely evaluation that provides useful lessons and recommendations for Management’s consideration and implementation. The evaluation reinforces management’s position that PBOs should continue to constitute an integral part of the services available to Bank clients. It also points out some of the areas where there is need for improvement.

Management broadly agrees with the recommendations, and it proposes response actions in the attached Management Action Record.

1. Dissemination of Evaluation Findings

After the evaluation findings were presented to the Development Effectiveness Committee (CODE) on 2 October 2018, the evaluation summary report was published on the Independent Development Evaluation website and a brief presentation of the key findings were made available online and in print. The reports of the two clusters, together with the 10-case study reports, were also published on the website.

In addition, the evaluation findings were shared at the following events:

- African Development Fund F-14 Mid-Term Review Meeting on 26 October 2018 in Kigali, Rwanda.

- The African Evaluation Association 9th Biennial International Conference on 14 March 2019 in Abidjan, Cote d’Ivoire.

- Workshops on “Proceeding of Optimizing the AfDB’s PBOs as Package of Support” on 21 May 2019 in Pretoria, South Africa; on 28 May 2019 in Nairobi, Kenya; and on 26 June in Abidjan, Cote d’Ivoire.

- Private sector development learning session on 30 October 2019, in Abidjan, Cote d’Ivoire.

2. Emerging issues

In 2017, AfDB approved a new lending instrument: results-based financing (RBF). RBF supports government-owned sector programs and links disbursements directly to the achievement of program results. However, due to its recent approval and implementation, this instrument has not yet been evaluated.

Since the presentation of the findings of the evaluation to the CODE in October 2018, AfDB has taken several actions to implement the main recommendations.

- Staff training

- AfDB staff received training in February 2020 on how to plan and effectively conduct policy dialogue, and on the design of results frameworks for PBOs.

- AfDB is developing e-courses for task managers, which will include a module on program-based operations.

- Preparation of guides to enhance the quality and effectiveness of PBOs