Clement Bansé and Stephanie Yoboué. The Independent Development Evaluation at the African Development Bank Group (AfDB) carried out two major independent evaluations of the policy-based operation (PBO) instrument. In 2011, it conducted an evaluation that covered 1999–2009; in 2018, it conducted an evaluation that covered 2012–17. The chapter draws on both evaluations, supplemented by recent data.

PBOs are fast-disbursing financing instruments AfDB provides to countries as loans or grants. They address the actual, planned, or unexpected development financing requirements of AfDB’s Regional Member Countries.

The evaluation found that PBOs remained a relevant and useful instrument for AfDB and its clients, although PBOs were challenging to design and manage effectively. It found the relevance of the PBOs in AfDB’s portfolio to be broadly satisfactory, based on their programming, design, and broad adherence to AfDB’s policy and guidelines as well as international good practice. As for the achievement of reform objectives, the overall picture was also satisfactory.

It was much harder to find evidence of AfDB’s influence on reform direction and speed. Even in the presence of strong ownership, concerns about the institutional and financial dimensions of sustainability meant that the outlook for sustainability in the sectors examined was unsatisfactory.

AfDB deployed UA7.2 billion (about $10.8 billion) in PBOs in 2012–17, but it did not invest in its own institutional infrastructure to obtain maximum value from the instrument. As reflected in its 2012 policy, PBOs were expected to form part of a “package of support,” to ensure that they influenced and supported reform agendas while providing important funding. This package included analytical work to inform technical input, policy dialogue, and capacity support. In practice, AfDB underperformed with policy dialogue, despite its strong position as a trusted partner, partly because of its institutional arrangements; the lack of clarity about who was responsible for policy dialogue; the way the dialogue was conducted, reported, and coordinated; and a lack of investment in human resources to conduct it. In addition, AfDB underperformed in providing timely and adequate capacity support and specialized technical advice, partly because of the limited menu of instruments available with which to do so. These shortcomings had implications for how well AfDB influenced or added value to country reform paths.

The evaluation examined a range of programming issues. Although the overall picture was assessed to be broadly satisfactory, the evaluation identified areas that could be strengthened. First, use of most of the PBOs reviewed was envisaged in either the relevant country strategy paper or the midterm review, in line with the policy. However, assessment against the eligibility criteria usually was made for the first time during the PBO preparation phase. The justification for the type of PBO chosen could also have been stronger, especially when the PBO did not use the recommended programmatic approach.

Second, in two-thirds of the operations reviewed, the analytical underpinnings used were listed and relatively complete. However, exactly how this work informed or underpinned the design of the operation was not clear.

Third, although risk assessment was assessed as satisfactory in two-thirds of the operations reviewed, reputational risk was rarely explicitly considered. The risk mitigation measures, such as future capacity support to address current risks, were generally not convincing within the time frame of a PBO.

The evaluation cites many good examples of how AfDB coordinated with other development partners, notably during the identification and appraisal periods. AfDB staff took coordination seriously and invested in upfront work with other development partners. However, the in-depth assessment illustrated how difficult it was to sustain these initial high levels of coordination throughout the implementation phase. Moreover, following adoption of the G-20 Principles for Effective Coordination between the IMF and MDBs on Policy-Based Lending in 2017, in countries facing macroeconomic vulnerability MDBs needed to align with the IMF.

Although two-thirds of the PBO appraisal reports examined stated that complementary inputs could play an important role, only a handful explained how they were to do so. All PBO results frameworks defined baselines, targets, and means of verification, and integrated prior actions and triggers. However, over one-third were less than satisfactory because of (a) weaknesses in presenting a convincing results chain; (b) the large share of process- and action-based indicators; and (c) a lack of realism, particularly for single-year operations. The use of conditions was suitably selective; in programmatic operations they linked from one phase to the next to plot a medium-term path and were linked to broader dialogue frameworks.

PBOs were broadly disbursed and implemented promptly, although some receiving countries reported that disbursement was unpredictable. In line with expectations for the PBO instrument, the evaluation found that AfDB had disbursed funds fully and, compared with investment projects, quickly. In addition, implementation progress was rarely identified as a cause for concern. Nine of the 10 in-depth assessments were considered efficient in terms of transactions costs and the time taken to disburse the funds. Perceptions of timeliness and transactions costs varied among both staff and borrowers’ officials, however.

Perceptions of the efficiency and transactions costs of technical assistance or institutional support provided to support PBOs were negative. When it was provided, such support was slow and tended to arrive toward the end rather than at the beginning of a PBO series, partly because capacity support tended to be designed in parallel with PBOs rather than in advance and partly because of the limited set of instruments AfDB had available to provide small pieces of technical assistance, all of which operated like full projects rather than as rapidly deployable expertise.

AfDB did not use policy dialogue sufficiently or make best use of its “African voice” to ensure PBO results. This finding echoes that of the 2011 evaluation, which described AfDB as “punching below its weight” with policy dialogue. Only 3 of the 10 in-depth assessments had satisfactory frameworks for policy dialogue in the targeted sectors.

Some of AfDB’s practices were out of line with both its own policy and the practices of the World Bank and the European Union. First, PBO design and management remained somewhat centralized, led by either the Governance and Public Financial Management Coordination Office (ECGF) or sector departments. The extent to which country offices took up ownership varied significantly. Second, no centralized unit provided specialized support to PBO teams. ECGF staff task-managed most of AfDB’s general budget support. This lack of a central support unit, and the limited guidance and training provided to staff, starkly contrasted with the support available at the World Bank and the European Union.

Overall, the assessment of PBO effectiveness, which focused on energy, private sector environment (PSE), and PFM, was broadly satisfactory. The evaluation highlighted areas in which AfDB could focus to strengthen results, indicating how it could contribute to the direction and pace of reforms. Data from project completion reports and country strategy and program evaluations by the Independent Development Evaluation indicated that satisfactory assessment was likely to reflect the effectiveness of the broader portfolio. All but 1 of the 10 cases achieved or partially achieved all or most of the reform actions in the results framework (in one case, 25 percent of outputs were assessed as not having been achieved). No sector performed notably better than any other. In 7 of the 10 countries covered by the in-depth studies, the overall effectiveness in terms of achievement of the objectives stated in the Results Measurement Framework was considered satisfactory.

Across the 21 individually assessed components, two-thirds were assessed satisfactory in terms of achievement of “landmark policy changes.”35Landmark policy changes are budgetary or institutional changes of substance and influence targeted by PBOs within the set of intermediate outcomes (induced outputs) identified in the theory of change.In one-third of the components, AfDB’s influence on either the direction or pace of reforms was evident and was usually achieved, through analytical work, technical inputs, and policy dialogue. But AfDB staff respondents to the survey supported the view that AfDB’s influence was limited and strongest at the appraisal stage.

The sustainability of PBOs in energy, PSE, and PFM was assessed as unsatisfactory, particularly in relation to the institutional and financial dimensions of sustainability. Only 4 of the 10 in-depth assessments had good prospects for sustainability. Almost all 10 had laid strong foundations for sustainability in terms of government ownership and leadership, which should be at the core of the decision to proceed with a PBO. However, weak institutional and financial sustainability undermined the positive assessments of ownership. This trend was clear for energy, PSE, and PFM; it cannot be generalized across the whole PBO portfolio.

The evaluation evidence from AfDB and other institutions providing budget support in Africa indicates that the most often identified factors relating to country context were ownership, country capacity, and having a champion for reforms; the country’s socioeconomic status; and country systems. The most frequent factors relating to the budget support mechanism were the quality of design, programming, development partner coordination, and monitoring and the choice of indicators. The most often cited enabling factor was the quality of design. In terms of hindering performance, the most often cited factors were insufficient policy dialogue, high inefficiency and transactions costs, the poor choice of indicators, weak monitoring, and poor predictability.

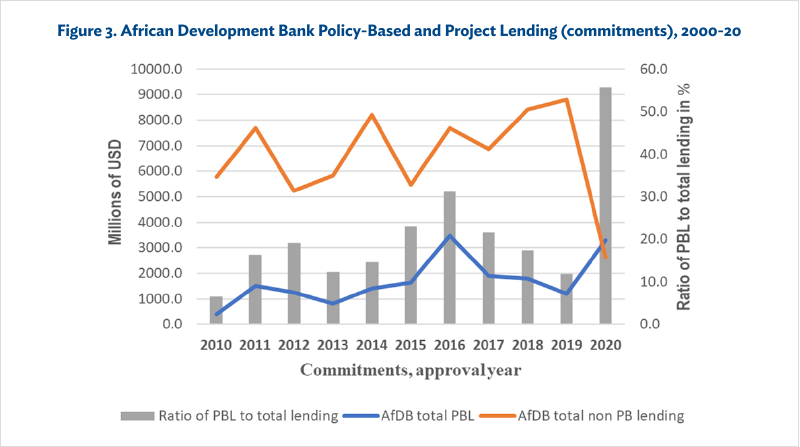

The most significant factors associated with achievement of landmark policy changes were programming, design, and efficiency factors; technical assistance; inclusion of the operation as part of a series; and the existence of a country office. These factors were even more important than the country’s socioeconomic status. AfDB’s policy-based and project lending (on commitment bases) for 2000–20 is shown in Figure 3. Although PBO lending increased during 2019–20, non-PBO lending fell sharply in 2020.

Note: PBL = policy-based lending

Source: Independent Evaluation Department, African Development Bank.

Comments by Alan Gelb

The chapter provides a useful overview of the evolution of PBOs at AfDB, which are described in terms of their evolving portfolio share, country distribution, variants, and focus. The chapter stimulates thinking on the evaluation of PBOs and on the institutional requirements needed to help with AfDB’s transition from a project-based to a policy-based bank.

These policy packages were contentious. Many saw them as impinging on national sovereignty—a sensitive issue, especially for newly independent countries. There were also genuine differences of view on what constituted an appropriate trade policy for African developing countries, some of which lacked a strong indigenous business sector, and on the role of the state in facilitating economic transformation. Still (and despite many critical views of the Washington Consensus), countries that stayed on track with macroeconomic and structural reform programs generally fared better than those that did not do so. Analysis based on the World Bank’s Country Policy and Institutional Assessment (CPIA) index suggested that countries with stronger macroeconomic and structural policies as well as more efficient resource allocations fared better than others. These findings suggest that many basic elements of economic management in these early PBOs were important, even if they were not sufficient, for a resumption of growth.

Given the increasing emphasis on PFM and economic governance, PBOs have shifted toward areas on which there is more consensus. Experts may debate the appropriate degree of trade protection, but it is rare to find arguments against more accountable public spending. This trend may not translate into easier implementation, however, because PFM reforms often confront strong entrenched interests and political opposition. They have a mixed record and, in some countries, governments have bypassed the reformed systems. As illustrated in the chapter, the third stage in the evolution of PBOs has been increasing the emphasis on sector policy components across a wide range of critical areas, although most PBOs have kept a strong focus on PFM.

The chapter suggests that PBOs tend to be provided mostly to middle-income countries (MICs), although the degree of concentration is difficult to assess without comparative data on the relative size of MIC economies in Africa or the cross-country distribution of the overall portfolio. As MICs generally have stronger PFM and likely greater policy stability, PBOs might seem more suitable in such countries, especially as programmatic operations or programmatic tranching. Offsetting this tendency, the chapter notes the use of the crisis window to provide quick-disbursing funds during the Ebola crisis and the COVID-19 pandemic, both of which had both health and economic crises. The chapter confirms the importance of having a mechanism available to combine policy, technical advice, and financial support at relatively short notice to countries beset by exogenous shocks.

Two-thirds of the assessed operations appear to have achieved landmark policy changes; where they did not, reasons were advanced to help explain why. But defining a results framework for PBOs against a clear counterfactual remains a challenge.

How can impact be assessed? Attribution is a fraught area for PBOs, especially where there are multiple development partners and operations are designed to support reform measures with strong country ownership and be well coordinated with programs of other partners. PBOs are intended to provide quick-disbursing support for the budget and to encourage policy and institutional reforms. The balance between these objectives varies, and the compatibility of these twin goals cannot be taken for granted. When financing needs are pressing, policy elements may take a back seat. It is also possible that the policy reforms required by an operation may be measures that the country would have undertaken anyway.

In these circumstances, it is probably best to recognize the problem and rest content with observing whether the operation came with the expected landmark policy changes, preferably ones set out in advance as part of a well-defined programmatic or tranching operation. One-third of AfDB PBOs do not fall into one of these categories, and the share of PBOs with full programmatic tranching is modest (less than one-quarter). As loan triggers tend to become more substantive in the later years of a program, more such operations will likely be truncated, with disbursement rates above zero but less than 100 percent.

To be effective PBO partners, funding institutions need to have the capacity to engage in policy dialogue at a high level and across critical areas, including macroeconomic management (to complement the work of the IMF, public sector and budget management, and sector policy). The chapter paints a picture of the evolution of AfDB, from project lending to an institution balanced between projects and policy and program engagement. Acquiring and sustaining capacity requires a strong analytical focus, through economic and sector work, together with research and analytical support. Doing so is challenging for any institution; as the chapter notes, for AfDB that work is still incomplete. The resource requirements of achieving this analytical basis across the full range of development sectors and policies may mean a degree of operational selectivity focused on areas of traditional strength. Substantial and continuing investment in capacity seems to be essential for AfDB to exploit its “African voice” in policy dialogue, even though it is not necessarily the major player in the region. A policy-based bank that functions well will also need the expertise and flexibility to offer complementary and timely packages of technical cooperation, a shortcoming identified in the chapter.

If policy dialogue and reform, rather than quick-disbursing funding, is to be the driver of non-project lending, it may be useful to consider other modalities to complement, or even replace, traditional PBOs, especially considering the shift toward a larger component of sector reforms. Results-based lending, such as the World Bank’s Program-for-Results (PforR) instrument is one possibility. Like PBOs, PforR financing is provided to the government treasury, disbursed using country systems, and not necessarily tied to program costs. The multiyear nature of PforR operations allows countries sufficient time to move beyond immediate outputs and toward measures of outcomes and impacts, allowing for a more substantive results framework than those of many PBOs. Experience with this new instrument is still limited, but it could become a successor to sector-based PBOs.

- 35Landmark policy changes are budgetary or institutional changes of substance and influence targeted by PBOs within the set of intermediate outcomes (induced outputs) identified in the theory of change.